Sweden Clears Final Hurdle to Join NATO With Hungary Vote

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

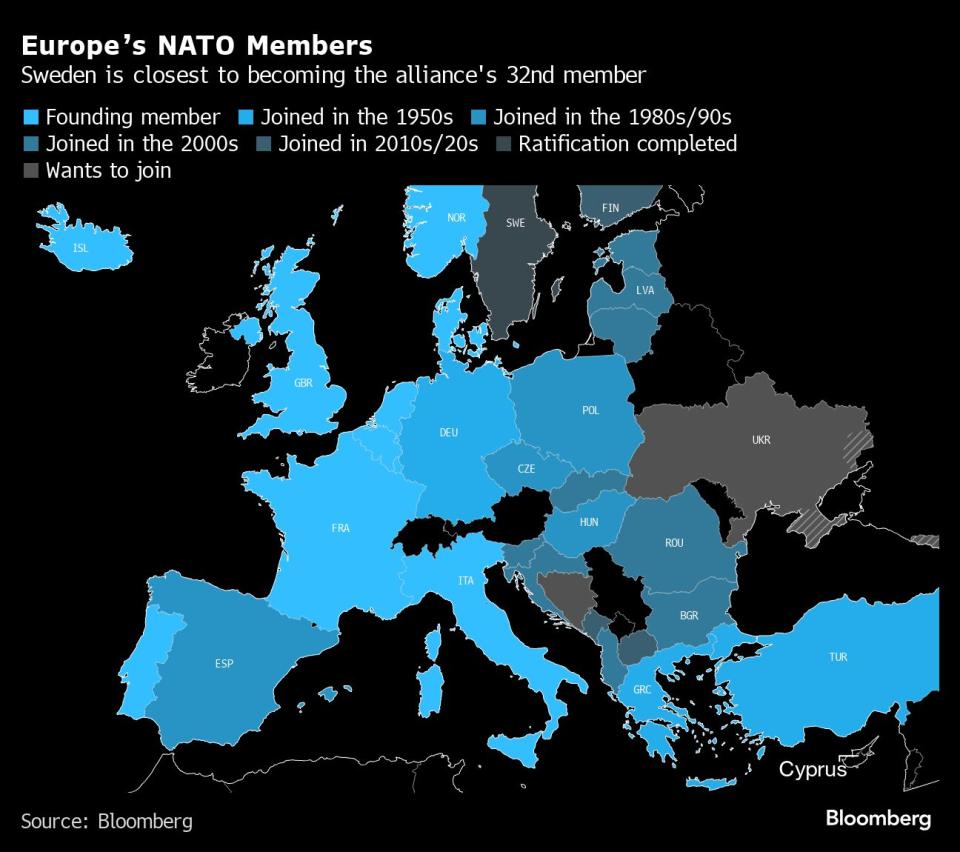

(Bloomberg) -- Sweden cleared the final obstacle to gaining NATO membership in a move that will solidify the alliance’s grip over Northern Europe and the Baltic region.

Most Read from Bloomberg

A Spike in Heart Disease Deaths Since Covid Is Puzzling Scientists

BYD’s New $233,450 EV Supercar to Rival Ferrari, Lamborghini

Treasuries Mixed Amid Another Flurry of Bond Sales: Markets Wrap

The approval by Hungary’s parliament on Monday came 21 months after the Nordic country submitted its membership bid jointly with Finland in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

With the wider war now in its third year and support to Kyiv flagging, Sweden’s accession into the North Atlantic Treaty Organization helps bolster Europe’s security amid rising concerns Russia could even target the bloc’s members in the future.

“Sweden now leaves 200 years of neutrality and non-alignment behind,” Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson told reporters in Stockholm. “That’s a big step — we should take that seriously. But it is also a very natural step to take.”

President Vladimir Putin’s aggression on Ukraine was partly aimed at preventing NATO from expanding further eastward. As Ukraine suffers from severe shortages of ammunition and has recently lost ground on the battlefield, there are fears that onslaught may represent just the first phase of broader imperial ambitions. Military leaders in Sweden have warned its citizens to be mentally prepared for war.

The Swedish membership is due to become finalized within a matter of days, once ratification documents are deposited with the US State Department, after which Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg will invite Sweden to accede to the Washington Treaty. No date for the ceremony has been set yet, Kristersson said.

When Finland became a member in April, it doubled the length of the border NATO shares with Russia. Adding Sweden strengthens the defense of that eastern flank, allowing the alliance to dominate the Baltic Sea region and facilitating the transit of troops and equipment from Norway’s North Sea ports to the east.

The accession also represents a momentous shift for a nation that pursued various versions of neutrality to stay out of wars for 200 years. The Russian invasion of Ukraine two years ago overturned Sweden’s security calculus, prompting an about-face by a government then led by the Social Democratic party, previously a staunch opponent of NATO membership for decades.

While Sweden was welcomed by most allies with open arms, the accession process has been a grueling experience, full of stops and starts. Turkey long demanded concessions, until it finally ratified in January after securing a US pledge on the sale of F-16 fighter jets. That left Hungary as the only holdout, even as Prime Minister Viktor Orban had vowed to not be the last country to pass the bid.

The Hungarian leader, who struggled to articulate the reason behind his foot-dragging, relented after a visit to Budapest by his Swedish counterpart last week. Portrayed by Orban as a trust-building exercise, the visit also involved the two countries agreeing on a sale of Swedish Gripen warplanes to Hungary’s air force.

Hungary’s approval is the latest in a string of high-profile issues where Orban ultimately relented. On Feb. 1, he dropped his opposition to an EU aid package he had vetoed less than two months prior. Orban has also reversed course on a pledge to block opening the path to Ukraine’s EU membership.

Bringing Sweden into NATO adds a technologically sophisticated military that has participated in the bloc’s exercises for decades. The Nordic country has a large defense industry sprung from its Cold War policy of being self-sufficient for its military needs. Today, Sweden is one of the world’s largest arms exporters per capita and the smallest nation that has developed modern fighter jets.

“When Sweden joins NATO, the Nordic region will have a common defense for the first time in 500 years,” Kristersson said. “We are neighbors, we remain friends and we become allies. We will defend freedom alongside the nations that are closest to us — geographically, emotionally and in terms of values.”

Its naval prowess and strategic location also will boost NATO’s ability to deter any Russian aggression against Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, which were under Moscow’s rule from the end of World War II until the Soviet Union fell apart in the early 1990s.

Before the Nordic countries’ accession, the three countries’ defenses mostly hinged on a 100-kilometer (62-mile) wide passage called the Suwalki Gap between Russian ally Belarus and the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad — a strip of land NATO allies would have to pass through to reinforce the Baltics in a conflict.

Sweden is joining NATO at a time when the alliance is grappling with growing uncertainty about the US’s commitment to European security. Donald Trump, who may return to the White House if he wins the elections in November, has suggested letting Russia attack members that don’t meet NATO’s spending goal. Even the current administration under President Joe Biden is facing difficulties passing aid for Ukraine’s defense against Russia, and the US has in recent years been shifting its focus away from Europe toward Asia, amid China’s rising might.

Sweden’s last major war was more than 200 years ago, when it lost what is now Finland to Russia in 1809. After avoiding two world wars and seeing its main adversary in Moscow collapse in the early 1990s, the Nordic country had made plans for another peaceful century. That approach was upended in February 2022, and along with NATO membership, Sweden is seeking to quickly rebuild its armed forces to face the growing threat.

General conscription was reintroduced in the wake of Russia’s initial invasion of Ukraine in 2014, and the country expects to reach NATO’s threshold for military outlays, at least 2% of gross domestic product, this year. That share is set to continue expanding, along with investments that are needed to prepare Swedish infrastructure for allied forces to traverse its territory.

When Sweden and Finland sought membership, Russia warned of “serious military and political consequences” that would require it to respond.

Asked about the potential for such a move now, Kristersson said there’s no knowing what Moscow will come up with.

“What we see constantly is disinformation campaigns, cyber attacks, that sort of thing,” he said. “We are prepared.”

--With assistance from Natalia Drozdiak, Zoltan Simon, Andras Gergely, Jeremy Diamond and Chris Miller.

(Updates with comments from Swedish prime minister from fourth paragraph.)

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

Elon Musk’s Vegas Tunnel Project Has Been Racking Up Safety Violations

Transcript: Did Musk Buy Twitter to Keep His Movements Secret?

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.