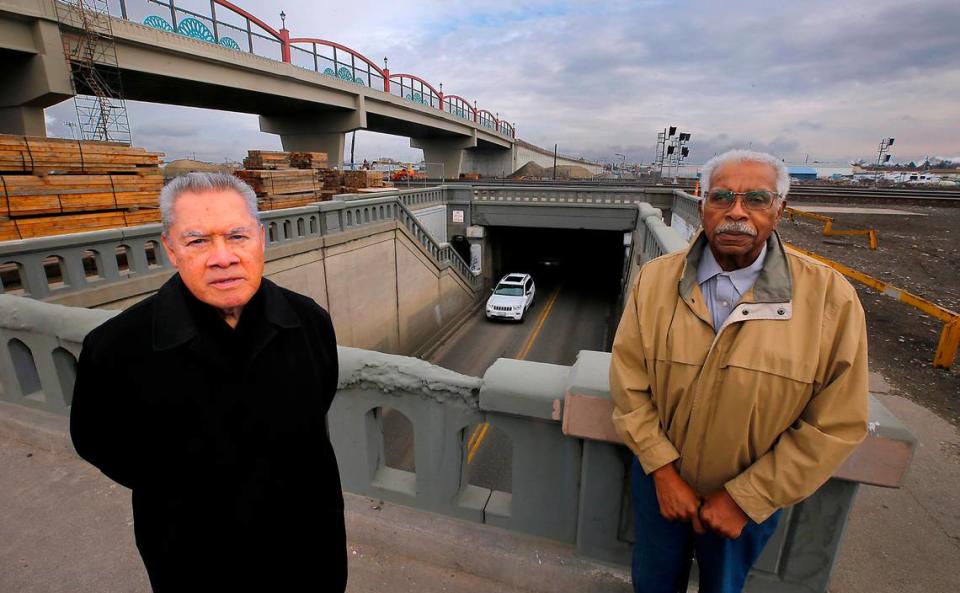

Symbol of racial segregation for many Blacks in Pasco is ‘a monument to our past’

It’s been more than six decades since Dallas Barnes last walked the shady contours of the Lewis Street underpass.

But taking one good look down the narrow, caged sidewalk brought back some childhood memories.

“The thing that I can remember is, usually, I’m walking with a bunch of kids and we would run under there screaming to get to the other side, just having fun,” Barnes, 83, said recently over the hum of passing cars.

“It was an adventurous time, looking back on it. We would just stump to the underpass and make a mad dash under there, hollering and screaming — and if it’s in the evening, (we would pretend) there was a ghost under there or something, so we ran a little faster.”

The underground Pasco structure has seen better days in its nearly 90 years.

For its first few decades, it served as an vital conduit — the only of its kind — to downtown businesses and services for Black and Asian Pasco residents living east of the BNSF railyard.

It also was a symbol of the racial segregation many Black families endured when they were barred for years from living in the city proper.

Today, the underpass is dark and dingy, lined with a hefty amount of graffiti, chipped paint and eroded concrete. The underpass also lies in the shadow of a new bridge under construction — the $36 million Lewis Street Overpass, with its crimson and teal fencing — that will soon replace the deteriorating structure.

While the underpass has lost its shine, its historical significance is not lost on long-time resident Felix Vargas.

“I see it as a monument to our past,” he told the Tri-City Herald. “It’s a bridge from one part of our community to another, and brought our residents together.”

That’s why Vargas, 79, says the city should preserve the underpass for future generations and use it for pedestrians.

But the city has other plans. Under pressure from BNSF Railway — the U.S.’s largest freight rail line — Pasco plans to demolish and fill in the Lewis Street underpass by early 2025.

On Monday, Feb. 26, cars will drive through it for the last time as the city plans to close it. Traffic needing to get across the tracks will be rerouted onto East A Street until the overpass opens in April.

A monument about the underpass is being planned and parts of the old structure may be preserved for that.

Connecting communities

Barnes said the underpass was the difference between being “welcomed” in your own community and “invited” into somebody else’s. Pasco was a community divided by the railroad, but connected by the narrow underpass.

Segregation was strong in the Tri-Cities during and after World War II, and the only place Black families could live and buy homes for a while was in the underdeveloped, under-serviced section of Pasco east of the railroad tracks.

The underpass served as a gateway for those families, and it was the meeting point between east and west Pasco.

The underpass was designed by Northern Pacific Railway and built in 1937, according to the Manhattan Project National Historical Park. Before opening the main east-west artery, Pasco residents were forced to cross the railroad on foot.

As a Black youth, Barnes lived on both sides of the tracks. He was never too far from the railroad tracks, either.

“Sometimes, catching the trains and riding a few blocks was part of the recreation,” Barnes said over the screech of locomotive brakes. “I don’t think it was going that fast because the roundhouse used to be there.”

Pasco was merely “tumbleweeds, toad frogs and a whole lot of freedom” when Barnes relocated to the Tri-Cities in 1952 when he was 12. It was a big change from the busy city life he’d known in St. Louis.

But he made the 1,900-mile journey to be with his mother and aunt, who previously migrated to the area during the Hanford workforce boom.

Along with Pasco’s semi-rural living came the realization of the area’s stark segregation practices. The difference living in Pasco was that you “knew you were being discriminated against,” Barnes told the Hanford History Project.

In east Pasco, where Black families were relegated to live, homes were mostly shacks, converted chicken coops or old trailers. Residents carried water from a few community taps and used outhouses, streets were unpaved and unlighted.

Even as Black Pasco residents cultivated culture and commerce in their own part of town — including churches, hotels, shops, restaurants and other businesses — there was always more on the other side of the tracks.

The underpass provided a straight shot for families to shop at businesses along 4th Avenue and West Lewis Street, including JC Penney and Sears, as well as several clothing outlets, drug stores, grocers and music shops.

At the same time, Barnes and his peers would frequent the Dew Drop Inn, a hangout for Black teens, where they would “dance, eat popcorn and tell lies.”

“This used to be the main freeway: Lewis Street,” Barnes said. “This was the connection between east and west. If you were going to leave Washington or Pasco, you would go this way.”

‘Access to the world’

Albert Wilkins, pastor of Morning Star Baptist Church, said they used the underpass to go to the movie theater or swimming pools on the west side of town.

“The underpass, for us as little kids, was a very scary place. Frankenstein lived down there,” the 73-year-old recalled. “You went down, and the lighting in there was so very dim. Because of the stories that got around — of Frankenstein, of Dracula and all those monsters that lived down there — when we would go down the stairs on the east side, and hit the floor, we would just run as fast as we could to the other stairs leading up.”

When Black youth surfaced on the other side of the underpass, Wilkins said, it was evident they were “in a different world” that was not kind to Blacks.

“There was always this sense of apprehension once you got to the west side of the underpass, and it didn’t feel safe,” Wilkins said. “That underpass was a line of demarcation. It was a divider of one community to another. And while I never saw any open hostility, there was.”

Vargas has fond memories of his father packing the family into their 1948 Pontiac and driving to the west side to pick up groceries, new school clothes and a hamburger for lunch. Driving through the underpass, he and his siblings pleaded with their father to honk the horn.

“This was the conduit. Without it, we didn’t have access to the world. So, it was very special,” he said.

Whittier Elementary School was the only school that existed on the east side until 1965. Before then, kids would be bused from the east side to attend secondary school at Pasco High School.

Vargas remembers vividly riding a school bus from Whittier Elementary School, through the underpass to the west side, to attend class at Longfellow Elementary School during desegregation.

He believes demolishing the underpass now would be a mistake. It should be preserved in some form because it documents and illustrates the history of the city, he said.

“Other countries that have been in existence for 300, 400 or 500 years more than our country have been able to preserve beautiful relics and pieces of structure like this that have been around for thousands of years,” Vargas said.

BNSF has required the city to remove the underpass within six months of the new overpass’s opening, a project that would cost local taxpayers at least an additional $2.5 million.

The city also agreed to relinquish the underpass easement in exchange for the overpass easement when it negotiated with BNSF for the project.

Vargas believes going back to the table with BNSF and looking at the financial cost of preserving the underpass would be worth the time and effort.

“I think we get so carried away with progress and development that we don’t care about the past anymore,” Vargas said. “We need to have a sense and appreciation for our history.”