'A systematic failure': How local districts make up unmet special education funding statutes

The Kansas Legislature has not provided sufficient funds for special education as outlined in its state statutes for more than a decade.

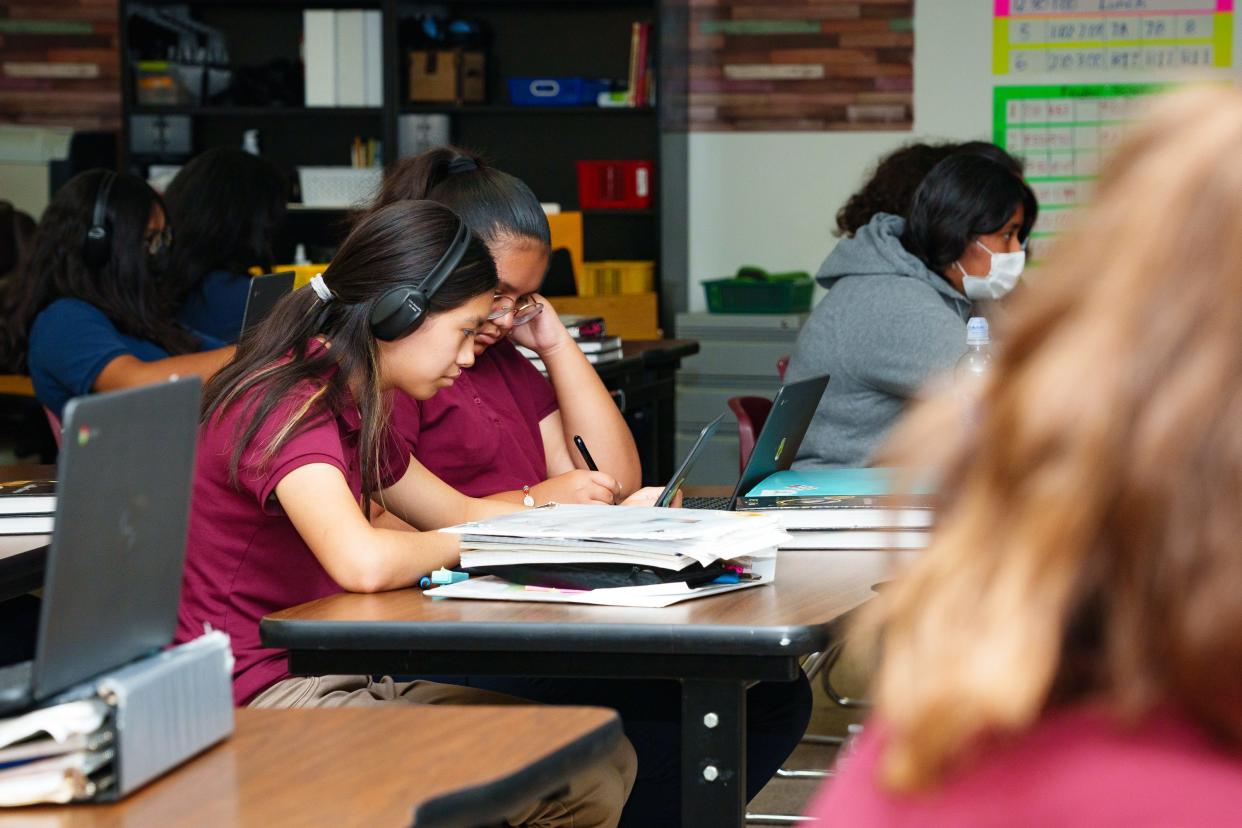

As teachers and their districts continue to struggle with resources for students with special needs, Salina Public Schools and other entities have made fully funding special education a priority going into 2023.

USD 305’s specific priority, as outlined in a tentative 2023 legislative priorities document, is for the state to fund special education at the 92% statutory level.

Special education services are mandated by federal law and Kansas regulations and statutes. Kansas law requires that 92% of the excess cost of special education be funded by the state in K.S.A 72-3422. But for the last few years, the state has been funding just around 76% of those excess costs.

The shortfall places the burden of meeting federal and state statutes on Kansans at the local level. Salina Public Schools diverts more than $2.4 million general fund dollars toward special education each year.

“Fully funding special ed would be a game changer for us,” said USD 305 Superintendent Linn Exline.

Making sense of special education funding

Special education budgets are a three-legged stool, comprised of federal, state and local monies. The federal government passed a law in the '70s that was amended and renamed in 1990 — the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act — which mandates special education services be provided to children with disabilities from birth through age 21.

The law granted all children a right to a free appropriate public education (referred to commonly as FAPE), which school districts are required to provide, including any special education services necessary to achieve a FAPE to students with disabilities.

The federal government vowed to pay 40% of the excess cost of providing students IDEA-mandated special education services, but most estimates place the federal contribution consistently around 14-16%.

State money, known as categorical aid in the realm of special education, serve as the primary source of funding for special education in Kansas.

And local aid is where the term “excess cost” comes into play. In its simplest terms, excess cost is the additional costs that accumulate to educate a typical special education student versus a typical general education student.

Jeff Hayes is the executive director of special education for Central Kansas Cooperative in Education, overseeing special education in 12 local districts.

Part of what confuses people regarding special education funds, Hayes said, is that it is not funded in the same manner as general education.

School district general fund budgets are based on student enrollment numbers, but special education budgets are based on the number of staff schools employ that are eligible to receive categorical aid.

There’s an assumption, Hayes said, that districts want more kids in special education because they will get more money, but since the funds are not per-pupil based, that would not even be possible. More staff doesn’t mean more funding, either, since categorical aid only covers a portion of the cost of staffing.

What makes things complicated on Hayes’ end, is that the co-op has to budget and prepare programming before it actually knows how much of the categorical aid districts will receive.

“At the end of the year, they’ll tell us how much our categorical aid is per staff member,” Hayes said. “We don’t actually know that right now, all we have are projections … No one, I think, that has any sense would set up a budget system that works this way, but it’s always been this way,” Hayes said.

This year, the Central Kansas Cooperative in Education budget is just under $30 million, serving 12 different districts. The federal government is funding about $4.5 to $5 million of the total co-op budget, categorical aid or state aid makes up $14 million, and $10.5 million was paid by the 12 local districts that make up the co-op.

Salina contributed $5.2 million in local funds this year to provide special education that wasn’t accounted for by state or federal dollars. The majority of the cooperative’s budget, about 96%, goes toward employing qualified staff.

When the federal government said it would fund 40% of IDEA, it didn’t make that mark a regulation or law. Instead, it sat as a target — a ceiling setting the maximum amount of the mandate it would fund.

In contrast, when Kansas set its statute to fund 92%, this was intended to be a base. Yet the state has systematically, in consecutive years, remained below its own mark.

After Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief funds and one-time federal Title VI funds run out, state categorical aid is likely to trend further downward, Hayes said. Projections his office has now sit around 65%.

“It’s like, OK, you’re systematically not funding resources that have been deemed necessary for a protected class,” Hayes said. “I mean how different is that than saying …‘we’ll fund it, but we’re just not going to do enough to fully fund it.’ Or, ‘we’re not going to fund programs for minority students, or students of color.' You would never say that. But yet, we’ve done that for years with kids with disabilities. How has that not gotten more attention?”

Kansas statues require more than federal law

Special education, Hayes said, is really about meeting federal law and Kansas statues and regulations. This can be different depending on the state, too.

“I can’t think of anything that Kansas provides beyond the federal statutes that I disagree with — they’re all good things,” Hayes said. “But to think that they don’t cost money would be foolish."

A few examples of what special education funds are also paying for in Kansas include:

Gifted education

Special education for students in private schools

Special education for homeschooled students

Administrative costs for other services

“Some of the discussion that I’ve heard is, ‘well, Kansas is spending more on special education than this state or that state,’” Hayes said. “And those conversations can quickly turn into comparisons that aren’t apples to apples.”

It used to be that if a district did not do partial enrollment, then homeschool students weren’t eligible for special education services. But after the passing of HB 2567, districts are now required to provide the option of partial enrollment to homeschooled students. This means those students may also be eligible for special education.

And students who attend private schools are eligible for special education, even though those schools don’t contribute to the local funds leg of the three-legged stool which supports special education in the state of Kansas.

The Central Kansas Cooperative in Education has staff in private schools that are provided through special education aid, per state statutes.

But the scope of what those teachers and staff work with in private schools is a very different scope of students than at local public schools, Hayes said. The private schools are open about being able to provide special education services, but if a student is too difficult for whatever reason, they can turn them away. A public school can’t say that.

“It’s not a bad thing that we provide support and services in private schools,” Hayes said. “But to think that it isn’t resulting in significant additional expenditures, compared to a state that might not use that same funding stream to fund those types of services, would be naïve.”

Special education funding and programing in Salina Public Schools

In Salina Public Schools, 21% of students have a disability that requires special education services. This number is continuing to grow, too, according to the district.

Exline said special education enrollment has gone up 20% since 2001 and special education students now make up a little over 23% of the district’s total enrollment.

This measures up with what Hayes has seen in nearly 30 years working with special education programming in the district.

What has changed over those three decades? The intensity of needs that are being met in schools.

“We educate everybody,” Hayes said. “I don’t think the general public has any idea about the type of students that are in our schools every day.”

A lot of programing, of course, goes back to the laws set by the federal and state governments. Public schools are put in a position where they can’t refuse a student service, but in many cases, can’t go above and beyond to meet the needs of some with current funding systems in place.

The demand for and cost of special education services has outpaced available funding for special education. Teachers and staff are faced with the challenge of educating students who have significant developmental disabilities and, at times, extremely aggressive behaviors.

A student with a history of juvenile delinquency and disruptive behavior, who also has a disability qualifying them for special education services, has a considerable amount of protection under the law and a right to be in school, Hayes said.

In a work session following a USD 305 school board meeting last week, executive staff in the district said increased special education funding will be necessary to ensure all students build skills needed for success after graduation.

“I think (special education) probably needs to be our highest singular federal priority,” Exline said.

This article originally appeared on Salina Journal: Special education a top priority for Salina schools despite state cuts