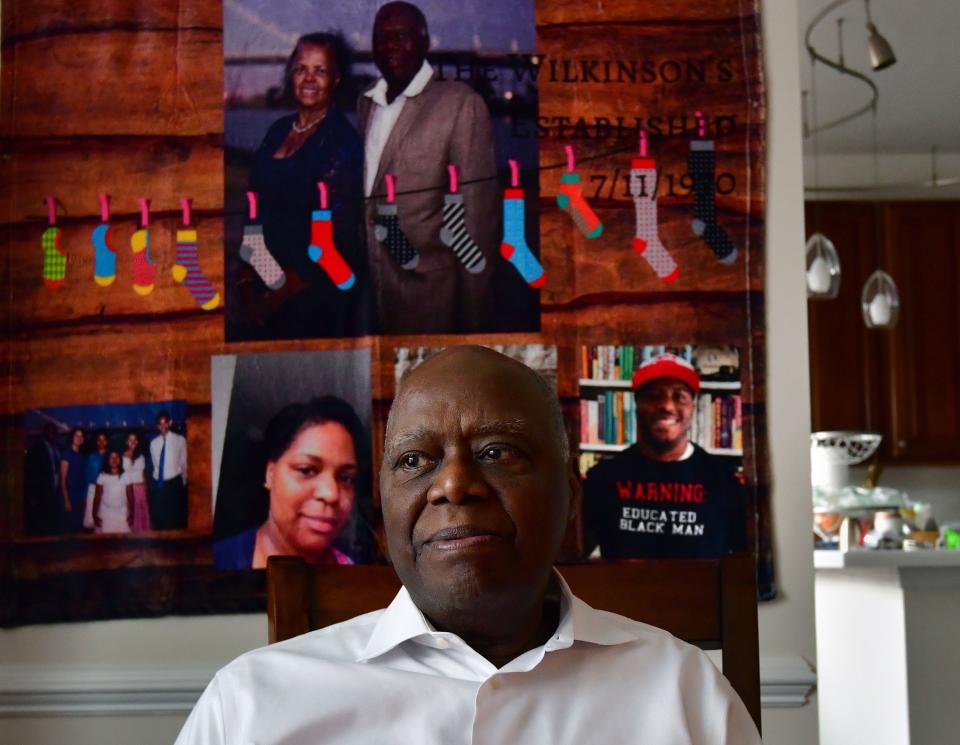

‘I can’t afford to get out of the game’ — Winston Wilkinson’s quest to becoming whole

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Winston Wilkinson grew up keenly aware that he lived in a world defined by boundaries. As a child in the 1950s, an 8-foot barbed wire fence separated his segregated community in Cedar Heights, Maryland, from the nearby white neighborhoods. And Wilkinson’s father, a strict disciplinarian and a community leader, held a firm grip on who got to come into the family’s home.

“He wanted his kids to grow up a certain way, so he created an environment based on his principles,” said Wilkinson, a Latter-day Saint who’s worked for three Republican administrations and led civil rights efforts in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services under President George W. Bush.

How a Black kid from a segregated Maryland community became a Republican politician who worshiped at different times as a Methodist, a Muslim and a Latter-day Saint is only part of the story, however. Ultimately Wilkinson’s life unfolded alongside a series of questions he never stopped asking himself.

“The thing for me was: Who was Winston Wilkinson?” And: “Where did he come from, and where was he going?” Wilkinson said in recent conversation with the Deseret News, shortly before the start of Black History Month.

At age 79, Wilkinson now knows where he’s going and shows no sign of slowing on his journey to get there.

He gets up at 4:30 in the morning, just like he did in Navy boot camp more than 60 years ago, and lifts weights at the gym. He serves on the board that governs Morgan State University, his alma mater and one of Maryland’s oldest historically Black colleges. He stays busy caring for his Latter-day Saint congregation as a bishopric member. With the current divisions in the country — and the party he’s dedicated his professional life to in flux — Wilkinson feels he can’t sit back. Officially, he retired last year, but his mind is swirling about what’s next: maybe sharing his wisdom with students, or starting a small consulting group around civil rights and higher education.

“I can’t afford to get out of the game,” he said.

He slips into the third person while talking about himself. It’s as if there are two Winstons inside of him, he tells me: one who looks at his past and the boundaries of the community that shaped him, and another who looks to the future.

A father’s influence

In the 1950s, Cedar Heights in Prince George’s County was a world unto itself. Families hung out at block parties and helped watch each other’s children. “The whole community raised us,” recalled Wilkinson’s friend, Larry Smith, who met 16-year-old Wilkinson on their way to a lawn party. The one thing the new friends had in common was the same family structure, Smith told me: a father who went to work and a mother who cared for the children at home.

“Our values were similar,” Smith said. “Everything was ‘yes, ma’am,’ ‘no, ma’am,’ ‘please and thank you.’” If the boys were up to mischief on a neighboring street, their mothers knew about it by the time the boys got home.

Wilkinson’s family went to a Methodist church and prayed at every meal. Wilkinson’s father set the ground rules for Wilkinson and his three sisters. Their warmhearted mother balanced out her husband’s rigidity, churning out homemade meals and caring for Wilkinson and his siblings. To make some extra cash — for Ban-Lon shirts, FootJoy shoes, gabardine slacks — Wilkinson and Smith got into caddying at Prince George’s country club golf course. Carrying bags for 18 holes for three or four dollars, they learned the game and played it at their makeshift golf course — a local brickyard, where they punctured a few holes in the clay surface.

At home in the living room, Wilkinson watched his father lead a civic association and hold community meetings, advocating for better roads and sewage in Cedar Heights. “I wasn’t interested in what he was doing, but I guess some things grew on me,” Wilkinson said. An employee at a government office, Curtis Wilkinson shielded his children from the racial inequalities beyond their community. “When he came home, he’d go into the bedroom and he’d leave it there,” Wilkinson said. “He didn’t want to poison my mind in terms of being able to grow and be successful.”

A witness to history

Wilkinson is lively with a generous smile and an air of thoughtful self-reflection that can only be cultivated over the years. A portrait of civil rights leader and Muslim minister Malcolm X, a gift from one of Wilkinson’s kids, hangs on the wall behind him as we speak. “He made me feel like a real person,” Wilkinson told me, recalling how he learned about the civil rights movement for the first time in the 1960s.

It was in the U.S. Navy, in 1962, that Wilkinson first began discovering who he was outside of the familiar Cedar Heights. He harbored a dream to travel the world, but instead was sent to Washington, D.C., to serve in the ceremonial honor guard during special events, state dinners and funerals. At age 18, Wilkinson found himself witnessing history.

Assigned to security detail during the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1963 march on Washington, he was trained to break up a riot with bayonets and tear gas. But after a meeting with other sailors, the group decided to take a nonviolent approach — “to lay down our weapons and do nothing.”

“I really believed that, for Blacks, nonviolence was the way to go and Martin Luther King was the guy to follow,” he told me.

On Nov. 25, 1963, Wilkinson marched with the mahogany casket containing the body of President John F. Kennedy down Pennsylvania Avenue to the Capitol Rotunda. “I was awestruck being around all the dignitaries,” Wilkinson said. “Coming from a segregated community, it didn’t hit me until later on in life who I was around.” One year in the Navy post turned into four, without Wilkinson ever stepping a foot on the ship.

When the woman who would become Wilkinson’s wife met him in a biology class at Morgan State University, he stood out from the crowd, she told me. “He was a little more distinguished than some of the other guys,” Gloria Wilkinson said. “He looked older, more mature.” And he had a penchant for deep questions, which she liked.

They married two years later.

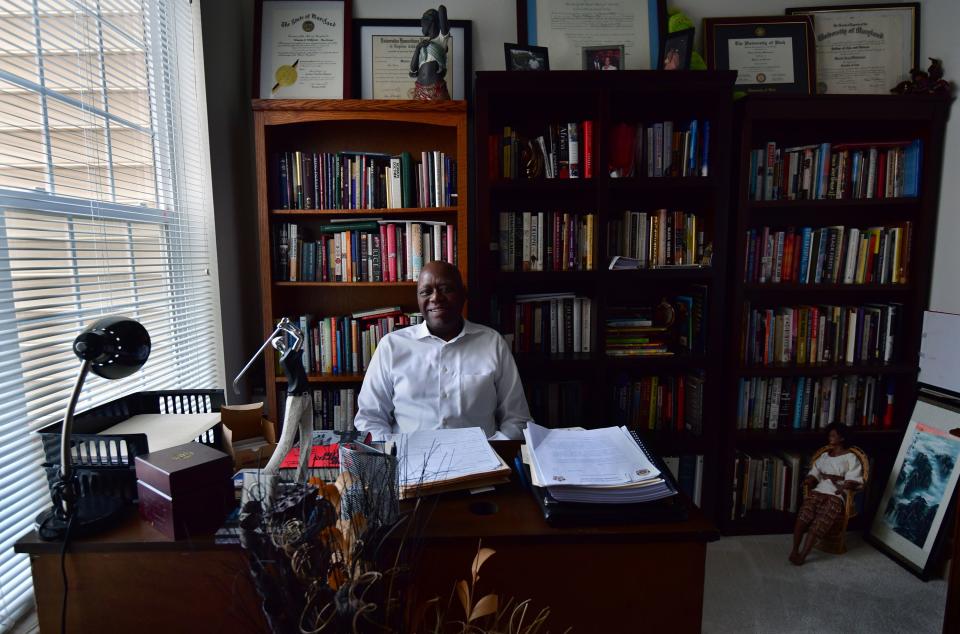

Wilkinson left Morgan State University with a degree in business in 1970 and turned his focus to law. Again, he was grappling with questions.

“What does it take to be a whole person?” was the question at the forefront of Wilkinson’s mind when he graduated from Howard University Law School. Intellectually, he seemed to have it covered, with a law degree under his belt. He was playing basketball and running. Spiritually, though, he sensed a void. “I decided that I was going to work on the spiritual part,” Wilkinson told me.

Inspired by Malcom X, Wilkinson and Gloria, now his wife, had converted to Islam — taking on Islamic names, praying five times a day, and attending services at a mosque. But he did not feel like this was his permanent spiritual home, and Wilkinson continued looking into other faiths. The family went back to the Methodist church, then tried an evangelical one. By then, the Wilkinsons had three kids, and they wanted them to grow up with a spiritual foundation. “We were trying to find ourselves in the religion — we wanted to have family togetherness there,” Gloria told me.

At the time, Wilkinson found his political footing. While he started out as a Democrat in Maryland, he had grown more conservative on fiscal issues and moderate on social issues. “Trying to find a party that fit that ideology was difficult,” he said. “At the time, the Republican Party came closest.”

Wilkinson describes himself as a middle-of-the road Republican. And it took a haphazard encounter with a Republican from Utah to get Wilkinson on a new spiritual path.

While working for the secretary of education, Terrence H. Bell, a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Wilkinson was milling around at a political event in Ocean City, Maryland. He struck up a conversation with Dallas Merrell, a Republican politician from Utah, who later became a regional representative for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The men started talking about religion, and Merrell invited Wilkinson to a dinner, along with Latter-day Saint missionaries.

“I had two lessons and I said, that makes sense in terms of where I am, who I am, and where I’m going,” Wilkinson told me. Gloria, however, wasn’t certain if, this time, the faith would stick. But after joining the church, Wilkinson finally had an answer, he said, to the questions he’d been asking his whole life: who he was and where he was going.

“I became a full being — mentally, physically and spiritually — a full Winston, who he is today,” he told me.

A changing party

Wilkinson later worked for Clarence Thomas, then assistant secretary of education for the Office of Civil Rights, now a Supreme Court justice. He went on to work for both Bush administrations, and he was director of the civil rights office under the Health and Human Services secretary and former Utah Gov. Michael Leavitt.

In 2001, Wilkinson was living in Utah and serving on the Salt Lake City County Council when he decided to run for Congress. Next to 12 white candidates, he stood out. But he didn’t mind that. “I told people at events jokingly they would never forget me,” Wilkinson said. “Because I’m the Black one on the ticket.”

Wilkinson came in third in the race, but right after that, he was elected to the National Republican Committee representing Utah. He was the only African American committee member in the United States.

“He became a role model to me in terms of how to respond to political conflict,” said James Evans, past chair of the Utah Republican Party, who alongside Wilkinson advocated to adopt the Martin Luther King holiday in Utah in 2000. “Politics is such rough and tumble — he always had this perspective of giving grace to people and allowing it to be.”

When Wilkinson gets together with his childhood friend Larry Smith, politics rarely comes up. They talk on the phone twice a week and have breakfast a couple times a month. Their political views don’t seem to matter. “He’s a Republican, I’m Democrat, but we’re close friends,” Wilkinson said. “Our friendship goes back to our families, understanding our community and its boundaries, and the respect we have for each other.”

Wilkinson laments the state of the Republican Party today; he says that after the rise of Donald Trump, the party is different. “It’s painful to watch where the party is right now,” he told me. “It’s not that party that I knew and that we were working to build.”

The right move

In 2015, Larry Hogan, then serving as the governor of Maryland, asked Wilkinson to come back to Baltimore to work for him. The two were friends, having met in 1970s while working to build up the Republican Party in Prince George’s County. Wilkinson prayed about leaving Utah, and the move felt right.

In Baltimore, as chief of staff of the governor’s Office of Community Initiatives, Wilkinson worked with churches and getting resources to people in need. Like his father, who died in 1975, Wilkinson was working to build up his community. “My hope was that I could be a role model in terms of my marriage and my involvement in the bigger system and I got where I am,” he said. “If Winston could do it — these guys could do it, too.”

In the pre-dawn hour every morning, Wilkinson looks at his father’s picture that sits on the dresser in his bedroom. “He had a vision for our little segregated community and he fought for it,” Wilkinson said. “He was a soldier. I get my strength from him.”