‘I can’t wait to go back to school’ — remote learning and the harm it has done to our kids

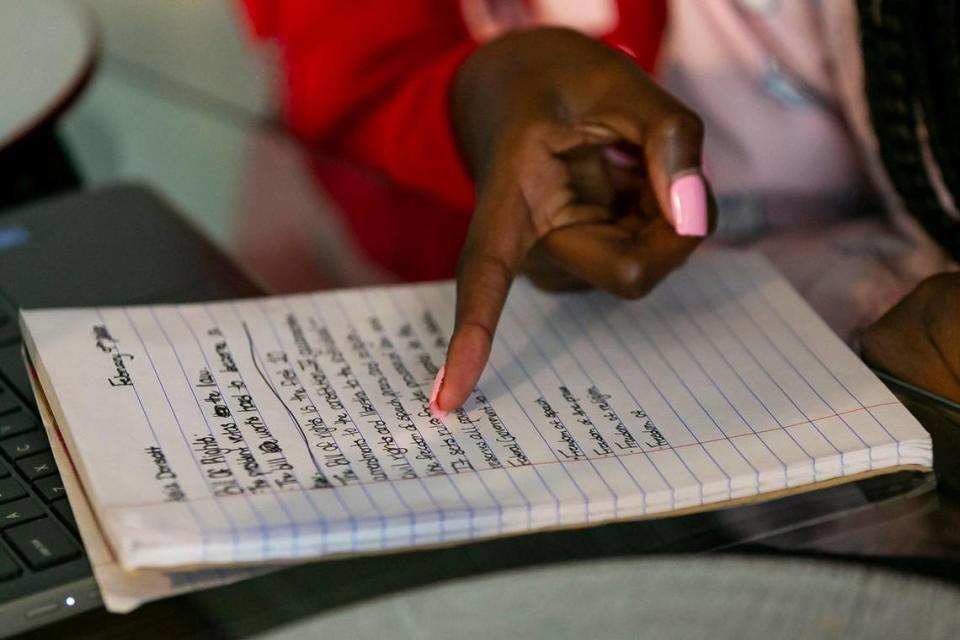

When Rashayna Jenkins opened her report card and counted four Fs among her seven grades, her spirits sank beneath another wave of bad news.

Then she got the warning letter from Miami-Dade Public Schools. She was in danger of failing eighth grade and should return to the classroom immediately.

For Rashayna, and most students, remote learning from home during the coronavirus pandemic has been a dysfunctional euphemism. They are not learning. Or they are struggling to learn from behind the barrier of a computer screen in virtual school, an inadequate simulation of in-person school.

“I hate it,” Rashayna said. “It’s boring and you can’t focus. A lot of work is burying you all at once. At home, there are distractions, and you stay up too late at night.

“Some teachers don’t make the camera mandatory, so you aim it at the ceiling and go on Instagram and TikTok or take a nap. I did it, and my grades dropped,” said Rashayna, who has since returned to school at Mater Grove Academy and shored up her grades.

In the year since South Florida schools shut their doors to bar the first surge of COVID-19, disruptions to one of society’s sturdiest institutions have been profound. Not only have students and teachers been separated by the digital divide, but they will feel the ripple effects of learning losses for years to come.

Just as the pandemic has disproportionately harmed the health of minority and low-income communities, it has widened educational inequities. And children, suffering from high rates of anxiety and depression, have been isolated from their peers at the precise time in their development when they need social interaction the most.

A return to the rhythms and rigor of regular school is essential to reversing the academic and emotional toll on what could be a lost generation of students, educational and medical experts say as districts hit the one-year mark coping with closures, reopenings, quarantines, hybrid classes and high numbers of absent or failing students.

“One of our top priorities must be getting kids back in school now that it is absolutely clear that the risks of staying home are higher than being in school, which science shows can be done safely,” said Dr. Jeffrey Brosco, pediatrician, professor of clinical pediatrics and associate director of the Mailman Center for Child Development at the University of Miami. “Kids are social creatures and a chief value of school is social learning. They need it. They miss it. Who would have thought our kids would say, ‘I can’t wait to go back to school.’”

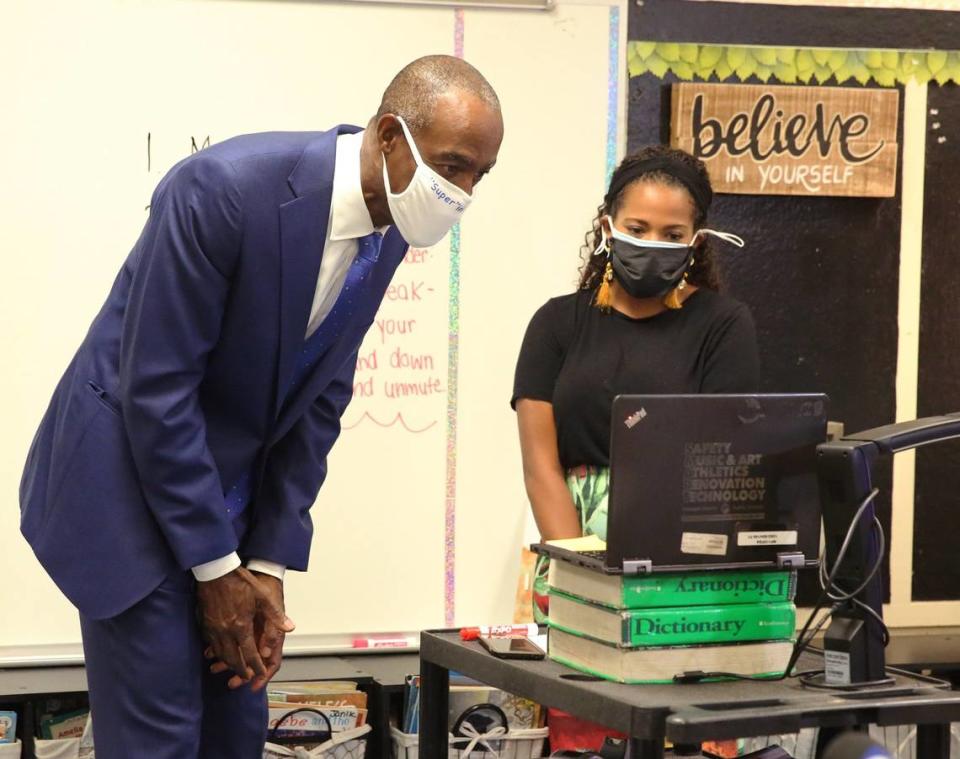

School closures combined with the reversion to online learning have created a public health crisis among young people, say doctors and educators, and Broward Schools Superintendent Robert Runcie’s alarming data proves it.

In his district of 204,000 students, sixth largest in the nation, where only 35 to 38 percent have returned to in-person school, he estimates that nearly 60,000 students “are struggling academically, socially and emotionally” and that 84 percent of those children are Black or Hispanic, 69 percent come from low-income households, 34 percent are English-language learners and 25 percent have disabilities.

“I think that’s reflective of what’s happening with Black and Brown communities across the country because of COVID,” Runcie said. “It’s the most vulnerable people being impacted to the greatest extent possible. These are kids that may have housing insecurity, food insecurity. They may not have conditions at home where they can focus on remote learning. They need to be in school.”

Startling numbers for Broward, Miami-Dade schools

In other signs of massive disengagement, the number of habitually truant students in Broward skyrocketed from 1,700 last year to 8,200 this year — a nearly 400 percent jump; the percentage of students who received one or more F’s by the end of the first grading period nearly tripled to 11 percent, and enrollment fell by 8,700, four times the normal annual decrease that is typically attributed to students’ movement to charter schools, Runcie said.

“Students will tell you that their relationships matter more than anything else,” he said. “Being able to connect with an adult in their lives can help keep them on track. Somebody they can confide in to deal with challenges they’re having. There’s no substitute for that.”

In Miami-Dade, the fourth-largest district in the country with 245,000 students in traditional public schools, Hispanics, who represent the majority of the system’s enrollment, lead the trend of about 45 percent returning to school, and that percentage is expected to rise, said Superintendent Alberto Carvalho, following a significant shift to at-home learning earlier in the school year when students yanked in and out of school by virus outbreaks opted to stay home.

A higher percentage of Black, Hispanic and Asian students have chosen to continue learning from home compared to the 53 percent of white non-Hispanic students who are back in the classroom.

Miami-Dade’s greatest concern has been with 10,000 missing students who never showed up for school and 10,300 online-only students identified as at risk of failing.

Of the students the district expected to enroll but were unaccounted for, the vast majority either enrolled in private school or elsewhere, or left the county, state or country, Carvalho said. About 500 students remain missing, he said, and are most likely English-language learners whose parents moved and whose phones were disconnected.

The district sent letters in January to students “not making adequate progress” and in danger of not graduating or being promoted to the next grade level and urged them to return to in-person school. Some weren’t logging on consistently and accrued excessive absences. The district made contact with 5,400 and, of those, 3,600 have returned to the classroom.

COVID shut schools down one year ago. What have we learned and how will we go forward?

“Many of these students are struggling not because of anything other than a disconnect of the modality that they’re in, which leads to current performance,” Carvalho said. “We believe based on the data that the game changer here is a combination of home circumstances that lead to a lack of supervision, inadequate monitoring and excessive absenteeism.”

Rashayna, 13, got the dreaded letter and went back to school last month. She was encouraged to go back by her older sister, Rashardra, 17, who has opted to continue online at Law Enforcement Officers’ Memorial High School because she would have to take Metrorail to get downtown and doesn’t want to risk exposing her family to the virus.

“I’m older and I’m making the honor roll online, but my sister was not understanding and retaining the work and couldn’t get extra help,” Rashardra said. “Many days she was crying out of frustration. For younger kids, there’s too much free time at home. In school, they get that push from teachers. She’d be in online class but doing other things, watching TV, on her phone. She fell off her routine.”

Irving Flood, a fourth-grader, went back to George Washington Carver Elementary at his mother’s urging after spending the first half of the school year online at home distracted by his 3-year-old sister and internet glitches.

“At first I was afraid of getting sick and coughing on my family but I’m not afraid anymore,” he said. “I can concentrate better at school. I can see my friends. At home I had to change my sister’s Pamper and get her juice and she’d go on my computer to watch Mickey Mouse and Bubble Guppies and play games.

“My auntie was at our house going to online school in the living room. Sometimes the internet would freeze or go out and we couldn’t hear our teachers.”

But other kids have stayed home, often unsupervised while their parents are at work or unable to find a quiet, fully connected space to study, and school becomes an afterthought.

“Some of the report cards I’ve seen are horrific,” said Sylvia Jordan, who has been running the Barnyard community center in West Coconut Grove for 37 years. “Ronald, he’s one of our future scientists, I don’t know how but he got an F in science.

“For some kids, teachers just wrote a question mark instead of a grade: ‘Did not attend class enough days to assess.’”

Losing the structure of the school day

The Barnyard, like neighborhood schools, is a sun around which communities revolve, but COVID knocked them out of orbit. Lives were turned inside out by lockdowns, lost jobs, illness and death. Disoriented and disconnected, kids have been forced to navigate through a year of chaos.

“School provided structure and sanctuary,” said Barnyard Program Manager Daniel McElligott. “Now it’s like these kids are feral.”

Several Barnyard regulars have been AWOL for months. Jordan shook her head when she talked about a boy named Malik.

“He should be in a gifted program. He made all sorts of things with Legos. He could name the planets and the dinosaurs,” she said. “But we heard his family was evicted and moved south. He showed up at our Christmas party. He told me he had not been attending school at all.”

Jordan and McElligott say screen addiction is a pandemic in and of itself among children and they fear their brains and personalities have been altered by COVID-driven dependency on computers and cellphones.

“The kids learning remotely don’t come in as much or when they do they are constantly on their phones,” McElligott said. “Social media, video games — it’s tough to crack the hold technology has on them now.”

They mentioned a boy named John, “very smart, very curious, very creative — and he doesn’t even want to do art anymore,” Jordan said. “He liked to write and fill up journals, but the spark has dimmed. He’s not the same child. It’s a shift to a more robotic mindset. They don’t even want to go outside and play, and children learn a lot through play.”

Anxiety levels compounded by screen time

Cellphones and social media are engineered to make users crave digital self-validation, an effect heightened by pandemic isolation, thus diverting kids from the natural pathways they’d follow to develop their identities, Brosco said.

“Your online persona is not your real self, and we know that more time on screens, more time on social media equals more anxiety so it’s like their personal growth is being stunted,” Brosco said. ”I had a patient who compared himself to a jaguar he saw at the zoo pacing in circles — ‘That’s me!’ he said. For a year, kids have been collecting excess energy and a pent-up desire to interact. It’s painful for them.”

Older students also complain that they’re trapped in a remote learning malaise. Salomon Assouline, 17, an 11th-grader at Dr. Michael M. Krop Senior High School in northeast Miami-Dade, was a straight-A student confident about taking four Advanced Placement classes this year. His grades have fallen to mostly C’s.

Cut off from friends and extracurricular club activities, he feels lonely and unmotivated at home and is responsible for taking care of his disabled brother when his parents are out.

“There’s a lot of outside stressors that take away from homework,” he said. “I’m very tired of online learning on so many levels. I’m tired physically from having to stay awake all day in front of a computer. I’m tired of not learning. I just can’t do it. It’s been tough for me the whole time.”

For Saskia Jacob, freshman year at McArthur High in Hollywood has been one disappointment after another. She’s been unable to attend football or basketball games, try out for cheerleading or join clubs, and her grades have dipped from mostly C’s to mostly F’s.

“I would log in for eight hours and not learn anything,” said Jacob, who recently returned to in-person school. “You sit there and they talk, but it’s not processing.”

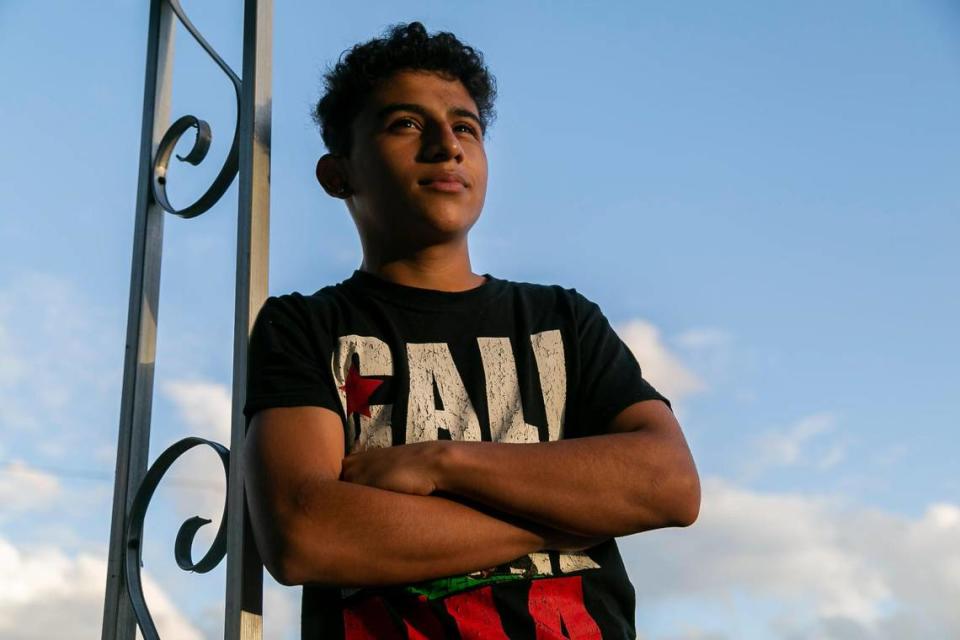

Flavio Cesar Gonzalez Cepero was adapting to life at American Senior High after moving to Hialeah from Mexico last year when the pandemic hit. He depended on conversations with friends and teachers to figure things out and learn English. Isolated from them, he lagged behind and his grades declined.

“I had a lot of doubts and I couldn’t ask anyone,” he said.

Parental involvement is key

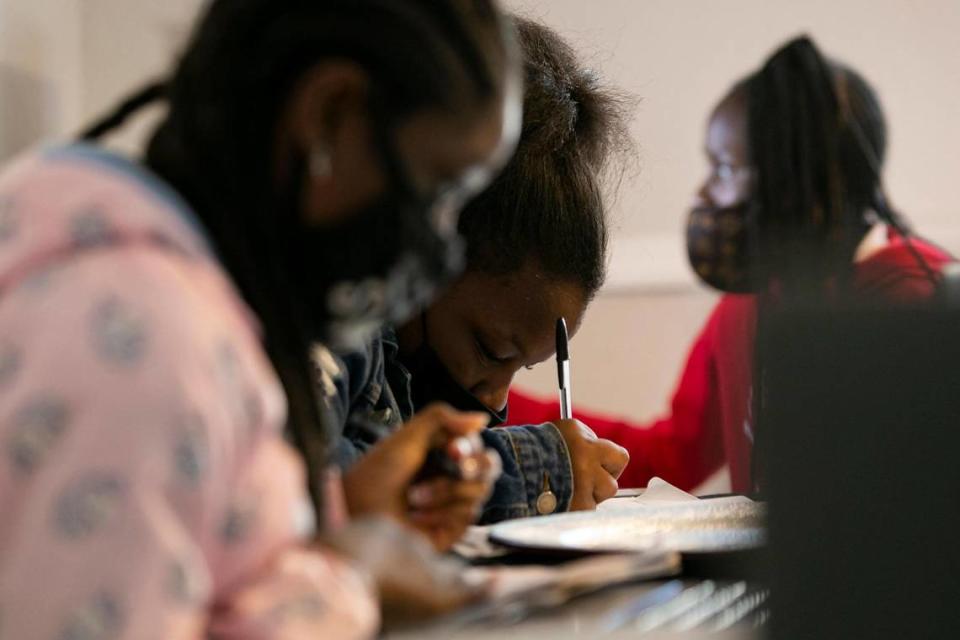

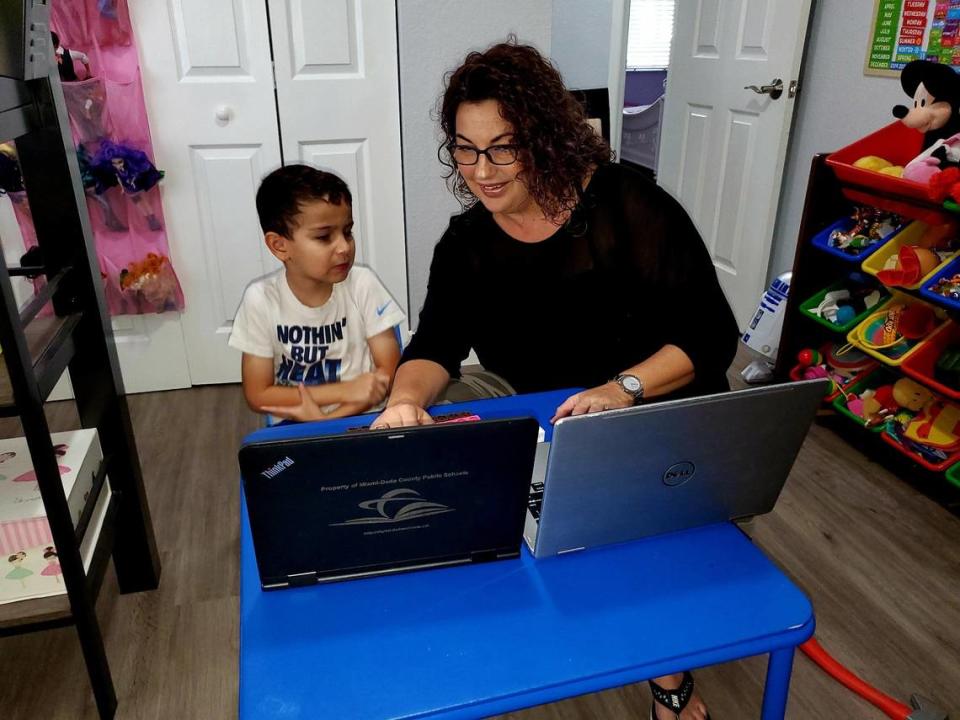

Students who thrive — or who have at least managed to stay afloat during the past year — usually have a parent or adult acting as guide, coach, monitor or troubleshooter. It’s like an additional job, especially for parents overseeing the at-home online learning of younger children who have shorter attention spans and scant organizational skills.

But it’s key to students’ performance, say educators and doctors, and places kids at a significant disadvantage if their parents are busy working outside the home, don’t speak English, or are not tech proficient.

Isabel Santos lost her job as an AmericanAirlines Arena chef and has been scrambling to work whatever odd jobs she can find to pay her rent. A single mom of three, she worries about her 12-year-old son who is home alone, learning remotely.

“To be honest, I don’t have time to watch over him and I don’t understand how to use a computer,” Santos said. “Our internet is not so good. I hope he’s going to school online all day. He better be doing his work. I tell him he’ll be in trouble if he’s not, but how would I really know?”

Tangelia Sands, a Liberty City mother of three, has taken charge of her kids’ education. She’s set up an afternoon study hall at her dining room table, and invites neighborhood kids to attend. She is part mentor, part boot-camp sergeant. She’s a full-time Miami-Dade County employee, but during the pandemic, she’s made an effort to work from home as often as possible.

Her daughter Summer Miller, 12, a Charles Drew K-8 student, and son LeBron Miller, 14, a Northwestern High freshman, are attending school in person but have done several 14-day quarantine stints at home when there were outbreaks at school. They told their mother about the online shenanigans of tech-savvy students, which convinced her they were better off at school.

“On Zoom, I observed how classes get disrupted and time gets wasted,” Sands said. “Some kids don’t log onto Zoom at all. And if they do, they can go to a breakout room, goof off, get answers from classmates. I’ve seen kids sleeping. If teachers don’t make the camera mandatory, kids turn it off and play video games.

“There are kids who are just not interested in school and if they can find a way online to get out of it, they will exploit it,’’ she said. “If they can find a shortcut online to advance to the next grade, they’ll take it. Zoom education is inferior in quality to the education kids receive when they are physically in school.”

Sands sets high expectations, and her eldest — Brandon Miller, 18, who graduated summa cum laude from Central High and serves in the Air Force — set an example for his siblings. Brandon, stationed in Texas, tutors his brother and sister and their friends over the phone. It’s all part of Sands’ plan not to let COVID derail Liberty City students.

“I know a lot of parents and grandparents do not have the time or knowledge to be a teacher’s aide at home. It’s exhausting,” she said. “But we’re not allowing COVID to be an excuse to slack off because once kids fall behind, it will be very hard to recover.”

Concern that students won’t catch up

Research studies on the impact of the pandemic on students project that many will suffer a full year of learning loss. Deposits that should have been made in students’ memory banks were not made, leaving a negative balance. The lower the quality of their remote learning environment, the less they have retained in the past year, including foundational reading, writing and math skills that are essential building blocks for future learning.

“What we’re seeing in statistical models is consistent with what I’m hearing from teachers: Remote learning is dependent on environmental factors, such as teachers who know how to deliver instruction that engages students, supervision at home from parents and access to good, consistent technology,” said Dr. Michelle Schladant, assistant director of the Mailman Center for Child Development at the University of Miami. “Kids in an ideal environment are doing as well or better than they would in class. But most are doing much worse. It’s a phenomenon we need to examine closely because the damage could be long-lasting.”

As losses compound, students could fall further behind, leading to an increase in dropouts, the studies show.

“Think about returning to school or the next grade without certain basic skills and the teacher has moved on. Those students have a learning gap and won’t simply catch up by working harder or faster,” Schladant said. “They’ll need tailored remediation. If they didn’t learn vocabulary development, phonemic awareness, letter knowledge, how will they progress in reading comprehension or writing skills? If they didn’t learn multiplication as thoroughly as they should have, what happens when they get to algebra?”

Schladant compares the deficits to what teachers call the “summer slide” — but 10 times as bad. Achievement gaps that already exist for students from low-income communities, for English language learners and for children with disabilities could grow wider, she said.

“Students at a disadvantage because of inequities in our society and our educational system are at risk of another achievement gap on top of that,” she said. “It’s going to be much harder for students and teachers in underserved areas to make up the losses and turn them into gains.”

Joanna Palmer was worried that her 7-year-old son Marcos was regressing on his social and emotional goals by staying home so she sent him back to Whigham Elementary in Cutler Bay, where he’s in a combined kindergarten-first grade class with other kids on the autism spectrum.

“In-person school with friends and a good teacher is what he needed,” Palmer said. “It was a big task to get him to pay attention and not zone out on the computer day after day.”

Without schools to anchor them, students are adrift. The 270,000 public school students still learning from home in Miami-Dade and Broward should go back to the classroom as soon as possible, said Shekhar Saxema, a psychiatry professor at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

“Children are finding it hard to learn and on top of that they can’t see their friends. They can’t indulge in their normal activities, the future is uncertain, and all the disparities in our country have become more pronounced under COVID,” he said. “They get frustrated because they know they are failing. Anxiety and depression are impacting children and young people at devastating rates.”

Teachers thrown into remote learning

Why hasn’t remote learning worked? It’s not the platform itself that spelled failure, but the way it was implemented on the fly as a temporary patch on a system designed for traditional schoolhouse classes. Teachers and students were not prepared, and were flung into virtual school during an unprecedented period of stress and trauma, said Dr. Christopher Gentile, managing partner at Cognizeo, an education tech consulting firm, and a pioneer in e-learning.

“Online learning has been around a long time, and successful schools like Florida Virtual School exist in almost every state,” he said. “But all of a sudden we threw everybody into the water, and online is not for everybody. It requires a paradigm shift in teaching strategies or younger kids will be lost and older kids will be bored to death.”

Districts throughout the country dropped the ball last summer when they did not train teachers, Gentile said. They assumed teachers could just transfer their lesson plans online or hastily arranged for them to use platforms that didn’t work, like Miami-Dade’s K12 fiasco with a computer software program that crashed the first week and had to be abandoned.

“Districts needed to look at COVID the way government does: It’s an emergency and we must provide resources and support to teachers, parents and students,” he said.

It takes a virtual school expert eight months to build an online high school history course. When schools closed last March, teachers were asked to improvise, then weren’t taught how to retool for the 2020-2021 school year. Removed from face-to-face interaction and hands-on learning, they’ve struggled to keep students engaged.

“Remote learning presents the challenge of breaking through the wall of the screen,” Gentile said. “You can’t just drone on through lectures. You have to design a model of active learning. You can’t manage the classroom by walking around and touching kids on the shoulder, looking them in the eye, seeing the cues that tell you if they’re getting it or they’re confused.

“COVID has highlighted that it takes a special breed of self-possessed, organized and motivated kid to succeed online. There’s a burden on parents. There are equity issues with technology, and we need to develop content that works on smartphones for kids who rely on smartphones for connectivity.”

Overtown school has one of the highest student return rates

Some schools have been pushing their neediest students to come back. That’s the case at Frederick Douglass Elementary in Overtown. The school has struggled academically and most of its students live in poverty. Yet 77 percent of its students are in class, one of the highest percentages in Miami-Dade.

“We just highly encouraged the parents that if they felt safe, their students should come on campus, and they did, and they’ve been coming ever since,” said Principal Veronica Bello, who has been strict about cleaning and distancing protocols. Douglass has logged three cases on the district’s COVID-19 dashboard: two staff members and one student.

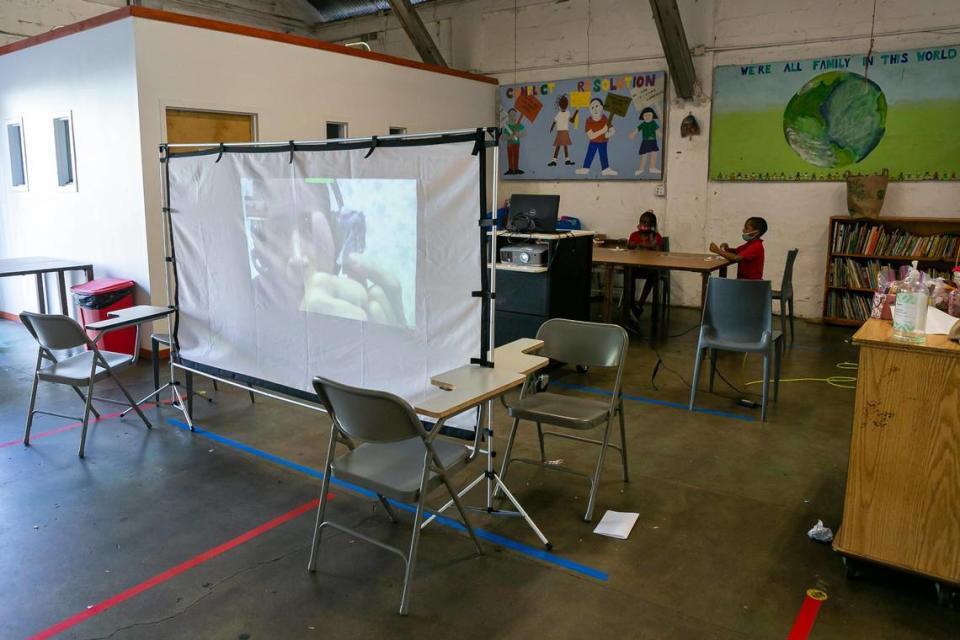

At the Barnyard, Jordan and McElligott have also made adjustments to keep tables separated and water fountains taped off. They’ve set up a big screen with a bedsheet for yoga and art classes via Zoom. Music has moved outside, where kids play with drums on picnic tables.

On a recent afternoon, while she helped a group of kids make collages, Jordan looked up to see John Largins stroll in. He’s the creative third-grader who’s been coming to the Barnyard less frequently and who Jordan feared had been lost to the dark side of Fortnight and TikTok. She was relieved to hear he’s returned to class at Carver Elementary.

“Yeah, I got tired of Zoom school,” Largins said. He’s glad to be back in school, where science is his favorite subject. “We’re learning about matter and stuff. I’m going to make a robot out of a soda can. I want to get straight A’s.”