Tackling substance abuse with families in mind to prevent foster care placements

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor's note: This is the fifth piece in a six-installment series about Native American children in South Dakota's foster care system, produced in partnership between the Argus Leader and South Dakota Searchlight.

Sobriety was a 12-year journey for Toni Handboy.

She tried to protect her children. She sent her daughter to live with her ex-husband in Oregon. Her son was placed with an aunt nearby after being removed by Child Protective Services.

But the impact on her children ran deep.

Even though Handboy tried to make sure her daughter never saw her high or drunk, her daughter was traumatized by her mother’s absence and broken promises.

Her son saw her struggle and was exposed to a violent relationship of Handboy’s. But he also saw her overcome.

Handboy got sober because of her children. She was determined they wouldn’t be placed into foster care like she’d been as a child. But they were also her lifeline; they encouraged her, supported her and kept her going each time she’d stumble on her way to recovery.

“It came full circle, being a child exposed to drugs and then being a mother addicted to it,” Handboy said. “I didn’t want my children to be exposed to it or suffer what I went through, because it’s a cycle, right? It’s going to carry through.”

Handboy’s story is one of many examined as part of an Argus Leader/South Dakota Searchlight investigation into the issues Native families and children face inside South Dakota’s child welfare system. Native American children accounted for nearly 74% of the foster care system at the end of fiscal year 2023 — despite accounting for only 13% of the state’s overall child population.

Nine out of 10 foster care placements in South Dakota involve substance abuse, said state Department of Social Services Secretary Matt Althoff.

But according to the National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect, substance abuse accounted for 57% of all placements in the state in 2021. It’s the second largest reason children are placed in foster care in South Dakota, according to the data.

State government officials recognize substance use disorder as a root cause leading to high foster care placements, and they say being proactive and addressing such issues are key to preventing children from entering the system in the first place. That includes stopping drug trafficking and maintaining healthy homes across the state, according to Gov. Kristi Noem, and getting parents into addiction counseling, according to Althoff.

"I don't think it's a lack of laws," Althoff said. "I think it is this reality that we make sure we're chasing the right causation as opposed to the symptoms."

The federal government is already funding preventative measures that address root causes of child removal and family separation through the Family First Prevention Plan. South Dakota is one of the last four states in the nation to create its mandatory three-year implementation plan.

But the state also lacks infrastructure to handle the number of parents seeking treatment. Substance abuse counselors, such as Handboy, and ICWA directors say the state’s reunification and parental termination timelines pressure parents and can lead to relapse.

Despite that, officials are positive about where the state can improve, especially regarding substance abuse prevention.

Rushing recovery timelines lead to relapse, re-entry into South Dakota foster system

Handboy is now a certified peer recovery specialist and a counselor for Wakpa Waste Counseling Services. It’s alarming how many of her addiction clients have lost their parental rights, she said. About 15% of her clients have children in the foster care system.

Substance use disorder clients addicted to methamphetamines need 18 to 24 months of rehabilitation and counseling before they feel confident in their recovery and sobriety, Handboy said.

But the state’s goal is to reunify families and discharge children from the foster care system as fast as possible, contradicting the reality parents face in their addiction recovery.

In fiscal year 2022, nearly two-thirds of the state’s child welfare reunifications occurred within a year, Althoff said during a legislative committee hearing earlier this year. The average time until reunification in that time period was 287 days.

"They're wanting these mothers to get their lives together within a year, otherwise they'll terminate their rights," Handboy said. "There's no way that's possible."

If they do get their children back in that timeframe without proper support or recovery in place, they're likely to relapse and their children will re-enter the child welfare system. The more times a child enters the child welfare system, the more likely a parent’s rights will be terminated.

According to the Children’s Bureau, part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, a quarter of South Dakota children placed into foster care in 2021 were re-entering the system.

Holly Christensen, executive director of the Sioux Falls-based nonprofit The Foster Network, said the state’s high re-entry rates are likely due to a lack of support for parents after reunification.

“Relapse is very common,” Christensen said. “How do they do that without fear of CPS coming back and taking their kids because they relapsed? Who can they call and be open and honest with and say, ‘Look, I relapsed and I need to go to treatment for 30 days.’”

Approaching addiction, keeping families intact: Family-based residential treatment in SD often reactive

South Dakota only has two providers in the state that offer family-based residential treatment, allowing women to enter the addiction program while pregnant or bring up to two children younger than 8 with them for the duration of their stay.

The two programs are based in Sioux Falls and Rapid City. The Sioux Falls program, New Start, had a waiting list of more than 20 people as of September.

Most clients are referred to the program through the courts, social services or parole recommendations, said Nikkie LaFortune, managing director of residential services with Volunteers of America, Dakotas, which runs New Start.

That means the program is mostly serving families who have already been impacted by the child welfare system in some way, serving as reactive treatment rather than as preventative treatment.

Family-based residential treatment can result in better outcomes for women and their children, both in supporting addiction recovery and keeping children out of the child welfare system.

The treatment combines intensive rehabilitation services with support through parenting, life skills and personal finance classes along with child care.

By ensuring women are able to stay away from drug use during pregnancy and strengthen bonds with their children, the treatment programs improve the health of the woman and increase the likelihood that women will complete treatment. Swap fathers into the picture, and the outcomes are also positive.

“It’s an emotional barrier for services,” said Becky Deelstra, marketing director for the VOA, Dakotas. “Even though a mom is struggling with addiction, that doesn’t mean she loves her kids any less. Being able to keep these moms with their kids is for their own benefit and makes it emotionally easier for them to enter into treatment.”

Three months after discharge from treatment, 80% of clients reported they hadn’t used drugs in the last 30 days, according to New Start data.

Despite documented success and research on the family-based residential treatment model, there are no similar programs in South Dakota’s rural areas, where nearly 43% of children’s families in the foster care system originate.

New Start, which started in 2000, can support 42 women at a time — tripling its capacity during a 2020 building expansion. The program served 408 mothers and 622 children between September 2018 and September 2023. Many clients stay for six months.

More: South Dakota inspired ICWA but still has high rate of Native children in foster care

But the program is struggling to maintain its staff. As of September, New Start had enough workers to support up to 30 clients.

Reimagining existing programs to treat substance abuse

It is not just "a program and a payment" that will make a difference in the intersection of substance abuse and child welfare, said South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem. There are several programs, facilities and support systems existing to ensure families receive the help they need.

Current preventative programming from the state includes child abuse awareness campaigns, fatherhood programming and parenting education, including a course on Positive Indian Parenting developed with curriculum from the National Indian Child Welfare Association.

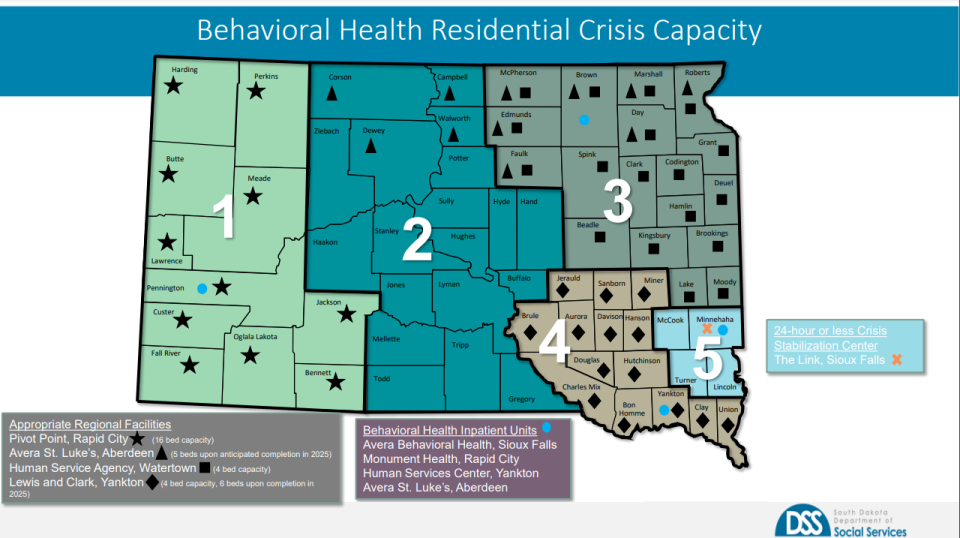

The state has expanded access to behavioral health and addiction treatment over the past three years and has planned investments for the next five years.

Noem added that her office is willing to create an agreement with tribal governments regarding outreach services on reservations, such as addiction treatment. Such agreements already exist in law enforcement and Child Protective Services.

"We're more than willing to do creative partnerships with our tribes if they're willing," Noem said.

Federal partnerships are already available. South Dakota is in its first year of creating a Family First prevention plan.

The prevention plans are a new way to use federal Title IV-E funding, which has historically only supplemented the cost of foster care. Instead, states can use a portion of those funds to pay for services that will help prevent children from entering or reentering the foster care system.

The state entered into a $1.2 million contract with out-of-state consulting firm ICF Inc. in June 2022 to begin developing the state’s plan and select evidence-based programs to invest in. There are 13 evidence-based practices in South Dakota that are well supported by scientific research: eight mental health programs, four substance abuse programs and eight parenting programs, according to the state DSS.

Noem’s administration and ICF have had meetings with representatives of most of the nine tribes in South Dakota to discuss the prevention plan.

"You've got to have prevention and intervention and training and services for when these families have a crisis," Noem said. "By only talking about these kids when they're already in the foster care system, that will do nothing to guarantee that we're not sitting here in 10 years again."

This article originally appeared on Sioux Falls Argus Leader: Keeping families intact can be important in substance abuse recovery