Taffy Brodesser-Akner Really, Really, Really Wanted to Write This Profile

This celebrity profile is going to start the way they all do-at least, most of the time, when they’re written by Taffy Brodesser-Akner: With an extensive back-and-forth about the plan. I’m hoping Taffy and I can do something that will steer me toward some grand epiphany about life, like when she hung out with Marie Kondo in her hotel room and realized that “we are all a mess, even when we’re done tidying.” Or something more intimate, like when she ate freshly steamed clams and grilled bread in Gwyneth Paltrow’s kitchen, just her and Gwyneth and Gwyneth’s new husband, Brad (“Her dress remained white,” Taffy wrote. “Mine had clam juice down the front”). Or something ridiculous, like when she went indoor sky diving with Melissa McCarthy. (“I hope you see the metaphor here,” her publicist had said to Taffy. “She’s flying, she’s up high, she’s soaring.”)

Unfortunately, Taffy is suddenly too busy for stunty activities. Her first book, Fleishman Is in Trouble, publishes Monday, and she’s been talking about it non-stop for weeks, doing interview after interview in addition to her full-time job (currently, she’s a writer at the New York Times magazine, which poached her from GQ). I’m actually the second writer Cosmo has sent (apparently it takes two people to profile The Profiler).

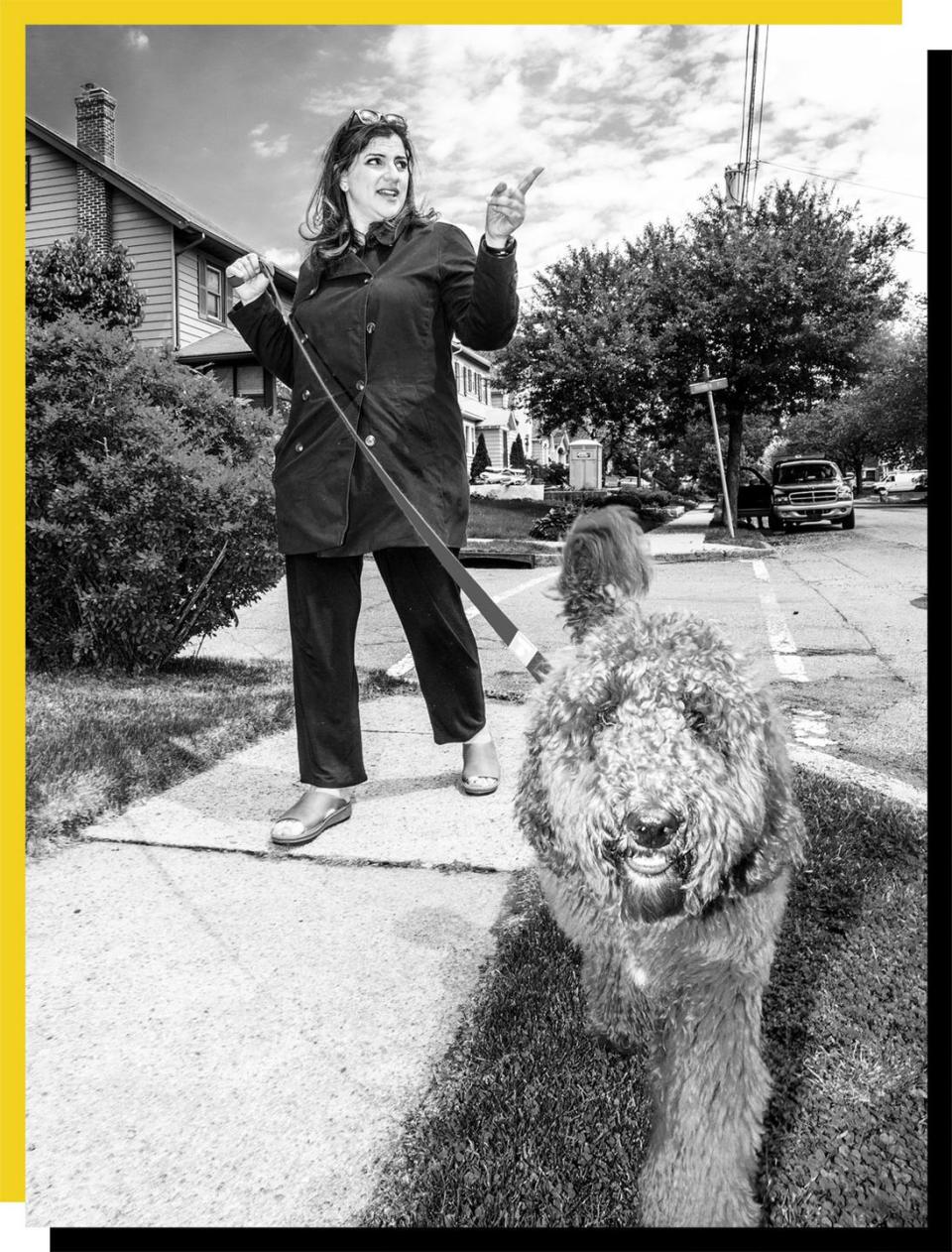

So while ideas are exchanged-a wax museum, a zoo-it’s soon clear I’ll be settling for something more obvious (and brief), like lunch in the West Village. When even that gets cancelled, I volunteer to talk to Taffy while she gets her hair and makeup done for a photoshoot. Her publicist says Taffy thinks that will be too loud (she knows as well as anyone that voice recorders pick up ambient noise). We eventually decide I’ll hire a car to take me to her place in New Jersey, pick her up, and ride with her back to Brooklyn, where she has yet another interview scheduled.

This is how I came to be standing in front of a two-story house in the suburb of Maplewood, next to a guy who’s here to finish installing the air conditioner. Taffy, 43, appears at the door to usher us in, smiling brightly in her comfortable jumpsuit; she hasn’t been this excited about a home improvement project since she had locks installed on the bathroom door next to the family room. I actually know Taffy from GQ, where I used to be the peon who did her expenses, so we immediately launch into office gossip. As we talk, her eyes get wide, and she waves her hands furiously, less to make a point than because her words literally move her.

We’re surrounded by evidence of her two kids-piles of sneakers, towers of board games-who sometimes make cameos in Taffy’s stories. One time, while she and Robert Pattinson were scheduling his interview for GQ, he offered to come here, to her house (“Yes, come on over, Rob. The kids get picked up at 3:50! Bring a snack or the younger one will bitch you out for hours!”).

Taffy often appears in her own work, too, a real-girl foil for the shiny people she writes about. Settling into our SUV, she says, “This is not me. I'm someone who sits in relative obscurity in sweatpants and sneakers and sometimes tweets.”

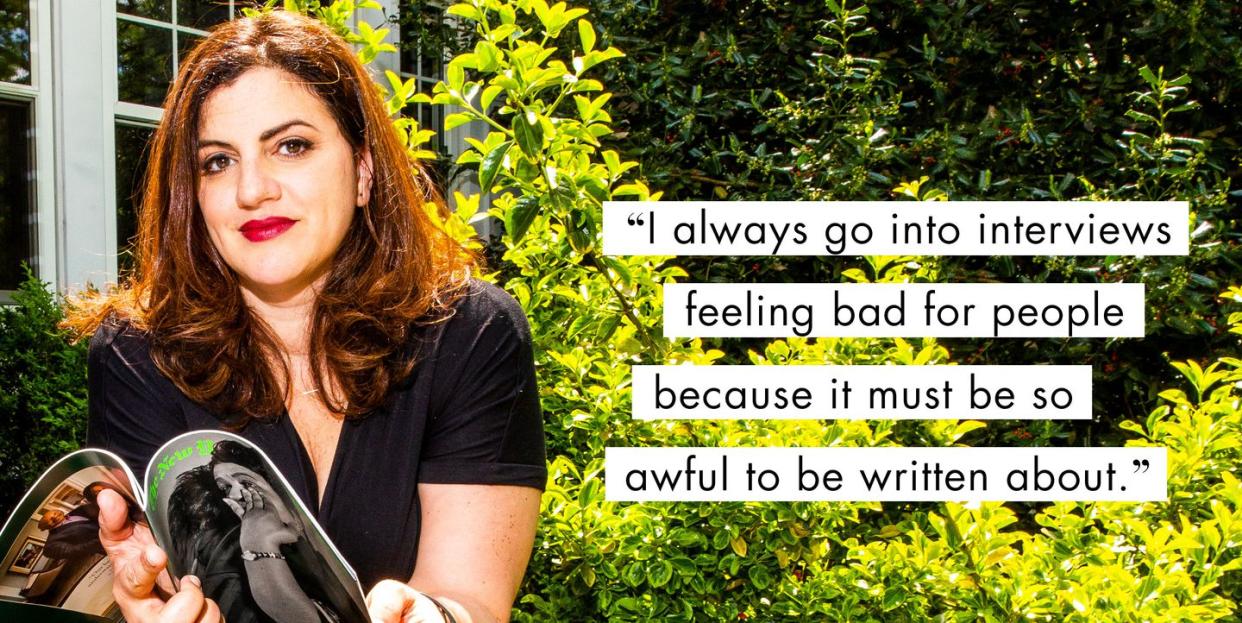

The change-up has been disorienting. She has churned out definitive, usually hilarious and often profound excavations of the inner life and artistic motivations of Bradley Cooper, Tom Hiddleston, Andy Cohen, Kris Jenner, Nicki Minaj, Ethan Hawke, Sam Smith, Chip and Joanna Gaines, Anne Hathaway, Kesha, and the guy who hosts The Bachelor. She’s usually the one deciding what to tell the world. It's been hard to cede control of the narrative, especially when the subject is herself. She hates, for example, that it’s my tape recorder sitting between us, not hers, and that she has to watch what she says. At night, she actually dreams she said the wrong thing to an interviewer. This anxiety has resulted in some micromanaging (“A great thing for me to stop doing would be telling people who are interviewing me how I would write a profile of myself if it were me,” she recently tweeted).

Indeed, this whole experience has given her even more empathy for her subjects. “I now really understand what a void, what an abyss, the powerlessness is,” Taffy says. It’s only been a few minutes into our car ride.

As any journalism school professor will tell you, the modern celebrity profile is aid to have started with Gay Talese’s enduring “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” an article published in Esquire in 1966. Writers have been lunching with singers and movie stars ever since for glossy magazines and now the Internet, attempting to draw out buzzy quotes or make sweeping conclusions about the culture. Lately, these profiles have been threatened by the rise of social media (celebs can now explain themselves to the public; they no longer need writers). But no one is working quite so enthusiastically to keep them alive as Taffy. She writes about other things besides celebrities-diet culture, #metoo in the jewelry industry-but her profiles have made her a star.

They always reveal something indelible about the real person behind the famous person. From her we learned that Tom Hiddleston is a totally stand-up guy who was bewildered that we all assumed his relationship with Taylor Swift was fake, and that Gwyneth smokes the occasional Nat Sherman without getting hooked, and can actually cook (in other words, is not a real person after all).

Like Talese, who didn’t even land an interview with Frank Sinatra, Taffy writes some of her most revealing pieces when she gets stonewalled. Her maddening attempts to plumb the guarded soul of Bradley Cooper sent her on a long tangent about why people deserve to know the artist behind the art-so they can “find themselves in someone else’s story, and feel a little less lonely in the world,” she wrote (but no pressure!).

Cooper didn’t love the piece, apparently. In one interview, he called it “disappointing.” Taffy tries not to get hung up on what her subjects think, since she’s not writing for them-she’s writing for us. But she does sometimes question the power she wields to tell others’ stories. “Is the thing I do, which I've become successful doing, is it unethical?” she wonders aloud at one point. “Is it too audacious?”

For her own turn in the spotlight, Taffy tried to do a lot of the explaining herself. It’s not hard to locate her in her art: Fleishman is narrated by a mom and former men’s magazine writer (hi, Taffy) who lives begrudgingly in New Jersey. The other main female character, Rachel, is a successful talent agent with her own firm who scraps for respect in a male-dominated industry but rarely gets home in time to see the kids (also: hi Taffy). The titular Fleishman is Toby, Rachel’s husband of 14 years, who is divorcing her and gleefully sexting (and sexing) his way through modern dating apps.

Lest you wonder whether the book means that Taffy and her husband, Claude, are headed for splitsville, she pretty much explained in the New York Times last week (in a piece that beat book reviewers to the punch) that her own parents’ divorce, when she was six, is what she’s really working through, since it left her “broken.”

But she knows lots of other people who are getting divorced too, she says. “I'm prepared for anyone at any point to call me and tell me they're getting divorced.” She can actually predict it, after leaving a party, whether the couple will get divorced or not. “They’re three months away from announcing their divorce,” she’ll tell Claude in the car. And she is always right. This strange intuition even works with celebrities. “Sometimes I will just have this tremor of the force,” she says. “I said out loud that Channing Tatum was going to get a divorce, and minutes later….”

Claude, she is quick to clarify, is not threatened by any of this, because he’s “a very secure person.” Here Taffy can’t resist a little stage-managing. “You asked me, ‘Am I worried about all the questions that are coming to me about my marriage?’” she says, “and what did I do? I started telling you how evolved my husband is and how well-adjusted we are. Claude’s great. He’s wonderful. He’s so handsome. We’re so happy. We never fight. It’s so weird. If I were you, I’d sit there and be like, ‘Yes, she’s terrified!’”

She pauses. “I sometimes wonder in all of this book promotion stuff, it's like, "Am I giving too much away?” she says. “Should I be reclusive?”

Taffy, nee Stephanie (“I was named after someone named Stephanie who was always called Taffy,” she explains), spent her adolescence in Canarsie, an especially inaccessible part of Brooklyn, where her mother moved her and her sisters after remarrying. She’d raised Taffy secularly until the age of 12, when she had suddenly become “truly Orthodox. Mega-Orthodox. Ultra-Orthodox,” wrote Taffy in the Times. This was a bit of a lifestyle change for Taffy, who was now surrounded by no one but super-observant Jews, and forced to watch TV in her basement as her “gateway to mainstream society,” she says.

When she finally made her escape, it was to NYU, where she studied screenwriting and eventually landed at MediaBistro, a start-up that offers resources to people aspiring to work at magazines and newspapers. This was no schmancy unpaid internship at the New Yorker. But she did meet Claude, who was teaching MediaBistro courses in Los Angeles and hosting a show on the local NPR station. She moved across the country to be with him, working out of MediaBistro’s L.A. office. And when the company sold, Taffy, by then pregnant with her first son, became “a dot com thousandaire,” she says. She saved her startup money to launch her freelance career, and when Claude landed a job as a politics writer at The Star-Ledger, in New Jersey, they moved back East.

Ironically, she landed in the world of men’s magazines only after being rejected by "a woman’s magazine that I will not name,” she says, that is located in the same building as GQ. This magazine told her “you’re not the kind of person we would hire for our story.” (“I think it was either the way I was dressed-which, for the record was a very nice black Anthropologie dress,” she recalls, “or the way I look? I don’t know. I just know that it was terrible.”). In that moment, Taffy sensed that if she did the thing she wanted to do, which was go home and cry, her career would be over. Maybe it sounds dramatic, especially knowing what we know now-she's Taffy, a verb and a noun. But at the time, she was thinking, I will never work again. This will destroy me.

So she stayed behind at the Conde Nast cafeteria to collect herself. There, she managed to fire off an email to an editor at GQ. I just happen to be in the building, she wrote. She had loved the magazine since her parents’ divorce, when her dad bought a single copy-“I guess to figure out what he should wear now,” she says-and kept it in his den for a next decade. “I read it over and over,” recalls Taffy.

The GQ editor wrote her back, and soon she was writing features about sugar babies and the Air Sex World Championships. That led to bigger assignments, like Nicki Minaj, who fell asleep multiple times while Taffy was interviewing her (and even stood defiantly with her back to Taffy for the first five minutes of the interview after being informed her videographer couldn’t capture their talk, though Taffy didn't include that part in her piece).

At first, at GQ, Taffy was the perfect student, gracious and accommodating and turning in stories on-time and spell-checked. But she learned that that’s not how the uh, other writers operated. “Over the course of my time at GQ, I learned the people who were considered geniuses, all men, were filing their stuff on closing day”-i.e., very, very late-"and that that almost added to their allure,” she recalls. In Fleishman, our narrator Libby describes a male coworker who “spent $7,000 on stripper tips once, submitted the expense without the receipt (naturally), and was reimbursed-even though no stripper ended up in the story.” Meanwhile Libby herself “had to check a second bag on a flight to Europe where I was interviewing an actor and I got a pissed-off call from our managing editor and I never did it again.”

As a woman at a men’s magazine, Taffy, er, Libby, found the most ambitious assignments frustratingly out of reach. She would never be the writer who got to “sleep on tour buses with bands or camp in the desert with an actor or do ayahuasca with a politician and come to the realization that he had to divorce his wife and marry his research assistant.”

But the real Taffy started getting more demanding. “When I started doing the ‘I don't get out of bed for less than $4 a word’ thing, people started paying me $4 a word,” she says.

The irony, of course, is that Taffy soon became the most well-known writer at GQ, more famous than the men who did ayahuasca with politicians (and surely with a bigger book deal to boot), and was poached by the New York Times in 2017. Now her profiles move the culture. She has been accused of being the reason Bradley Cooper didn’t get an Oscar nod. Her surreal profile of the unrepentant figure skater Tonya Harding (Margot Robbie played her in "I, Tonya") may or may not have contributed to Harding getting fired by her publicist a day after it published, when Harding proposed to fine any future journalists that ask about her past.

And despite the second novel she’s already working on about wealth and class, and the screenplay she’s co-writing about the IRL story of a 600-lb. man who bikes across the country to win his wife back, she still loves going deep on celebrities. She makes a solid case that they are, in fact, the actual most authentic humans. “What I love about interviewing rich people is that money is this huge problem for all of us,” she says, “and underneath our anxiety about money is who we really are. But half the time you can't get to it, because you're just so concerned about money.”

Taffy and I are now sitting outside a café across the street from Greenlight Bookstore in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, eating matching quinoa-avocado-tempeh bowls (she's recently gone mostly vegan for health reasons) and drinking elderflower lemonade. Soon Taffy has to head to a podast interview (she can’t even remember which one). But for now she’s got resting Mona Lisa face, a picture of calm in the storm, only checking her phone a handful of times to see if her agent or someone from her kids’ school is calling.

Fleishman, ultimately, is not just about marriage but about the reality of women being just generally unable to catch a break in today’s world, no matter what decisions we make. She wrote the book two years ago, before #metoo exploded, but fears it’s “timeless.” Early reviews have been rapturous. It’s “just the sort of thing that Philip Roth or John Updike might have produced in their prime (except, of course, that the author understands women),” raves Eat, Pray, Love author Liz Gilbert in a blurb. It “cares about its characters as people in a way that’s absent from the prose of [Tom] Wolfe-or, for that matter, Jonathan Franzen, whose work Brodesser-Akner evokes while confidently one-upping," adds Rolling Stone.

You may notice that the authors she’s being compared to are men, since it’s men who have traditionally been associated with Big Important Books. Even at GQ, "A lot of my success had to do with me being able to write about themes that were important to men," she says (such as, like, men).

And yet, her book publicity blitz has occasionally been deflating. “I've had a week of, what do they call it? Microaggressions,” she says. Too many dudes telling her they’re impressed with her book. “Which has this layer in it of, You exceeded my expectations but don't worry, they were pretty low,” she says. “It assumes that that's a compliment, that I was trying to impress you. Fuck you!”

One of the many clever tricks of Fleishman is that almost the entire book, while told in Libby’s voice, focuses on elucidating Toby’s point of view as the wronged, fragile, ultimately self-absorbed husband of a very successful woman. “I felt that the only way to tell a woman's story was to show how she is viewed by a man,” explains Taffy. “Because if we were all women, this would all be going fine, right?” She pauses. “I would not know how impressive I was to the men of the world!”

At one point during our car ride, crawling through traffic in lower Manhattan, we'd talked about the idea women are particularly susceptible to, that we don't actually measure up (um, hi, still out here profiling The Profiler!).

I can’t see Taffy’s eyes behind her clip-on sunglasses (they’re chicer than they sound, I promise) but I imagine they’re flashing. She felt this at GQ, she says. She even feels it now, or at least she did last week, even as all the rave reviews started rolling in, when she wondered whether she was on an "endless tour of congratulations for myself when it is not yet clear if I should congratulate myself." (At least that's settled now.)

"I hate to even say 'impostor syndrome,' because it's such a women's magazine cliché," she says, "and it's also a cliché to say that clichés come from somewhere."

"So how do we make this not a cliché?" she muses. "I don't know. I can't help you. You have to write this.”

Taffy Brodesser-Akner photographs: David Williams; Celebrity photographs: Getty Images

('You Might Also Like',)