Takeaways from new report on Wisconsin child care: It’s expensive, hard to find and politicians can’t agree on what to do

As child care programs prepare for a steep fiscal cliff and lawmakers debate how to best support the industry, Forward Analytics, the research arm of the Wisconsin Counties Association, released a new report on Wisconsin's child care crisis.

Many Wisconsin Democrats, including Gov. Tony Evers, are calling for funding to extend Child Care Counts, a stabilization payment program that relies on federal COVID-19 relief dollars, past January 2024, when it is slated to end.

Republicans are spearheading a package of bills that would instead create a loan program for providers, a child care reimbursement account not taxed by the state and change care regulations. They said they could introduce more child care and workforce proposals.

And last week, federal lawmakers introduced the Child Care Stabilization Act as COVID-19 relief funds run out later this week.

Here are some key takeaways from Forward Analytics’ report:

More: 4 takeaways about the high cost of child care in Wisconsin and nationwide

Child care is one of the greatest expenses for families — at a time when it's most difficult to afford

The younger the child, the more expensive the child care, in part because younger children require more individual attention and care from more providers, the report said. Center-based child care often costs more than family child care, or child care programs run out of providers' homes.

Child care for an infant consumes roughly 28% to 36% of the median household income of Wisconsin parents and guardians younger than 25, the report said. For older Wisconsin parents and guardians, between ages 25 and 44, child care for an infant charts between roughly 14% and 18% of their median household income, the report said.

Concurring with other recent reports, Forward Analytics found child care can cost more than college tuition.

Parents of college students have more time to save for their children's college, typically have well-established careers and help through scholarships and loans, said Forward Analytics' deputy director and the report's lead author, Kevin Dospoy.

It's a different story for parents needing child care.

"Typically when people start a family, they're at the earliest end of their working life, (so) they're making the least amount of money that they're going to make in their career, and they are now going to have to pay the most expensive bill that they may ever have to pay (child care)," Dospoy said, also adding that there are fewer cost-relief options for child care than college.

This steep cost burden shapes families' decisions, including when — or even if — families have more children and what shifts they can work.

The demand for child care in Wisconsin seems to be shrinking. But it's getting harder to find care.

In addition to high costs, Wisconsinites face another child care hurdle: It's hard to find.

This is largely because the number of Wisconsin's child care workers, which determines how many children a child care program can serve due to staff-to-child ratio requirements, decreased by 44% from 2010 to 2021, the report said.

The approximate 4% decline in the number of children in Wisconsin younger than 6 with all parents in the workforce during this same timeframe is no match for the large supply drop.

"Wisconsin is getting older, fewer people are having kids and when they do have kids they are having kids later, and fewer families are moving here with kids," Dospoy said. "So, we kind of expected the number of kids in need to decline, but the number of child care workers declined by four times that amount in the same time period."

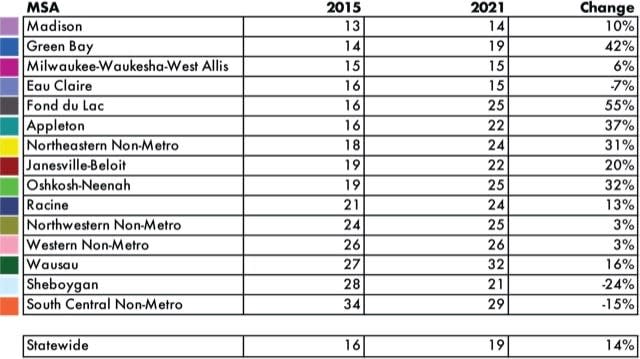

Between 2015 and 2021, accessing child care has become more challenging for the majority of Wisconsin, with Northeast Wisconsin seeing the largest decline in availability, the report found.

The areas of Wisconsin with the worst child care access, defined as having the most children younger than 6 per child care worker, are the Marathon County area, followed by the majority of rural Southern Wisconsin and some of central Wisconsin.

Even though child care has seen wage increases, pay still lags behind large majority of professions

A large factor in the shrinking child care supply is low compensation. In Wisconsin, the 2022 median hourly wage for a child care worker was $12.66, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. For a preschool teacher, it was $14.36.

Nationwide, out of 546 occupations, child care providers earned the 13th lowest wage in 2022, the report found. Using Wisconsin-specific data, Forward Analytics compared child care workers' 2022 wages to those 50 other occupations with similar education requirements. They found child care providers earned the second lowest wage.

Child Care Counts, which began in May 2020, allowed many child care businesses to boost wages and bonuses. But even with this help, the report said, other occupations' wages grew faster, and more started to exceed the pay of child care workers. This reality makes it hard for people to want to get into — or stay in — the child care profession.

"You look across the street at the retail box store or the warehouse and someone is making $10,000 more a year than you are with no requirements for education or advanced training," Dospoy said.

Because most of child care programs' revenue typically comes from the price parents pay for care, and programs already run on slim profit margins, increasing wages often means increasing what parents pay.

What's Wisconsin doing about the child care crisis?

It's unclear at this point, with Democrats pushing to extend Child Care Counts and Republicans rallying behind an entirely different plan outlined in proposed legislation.

Many child care providers are calling for Child Care Counts to be continued, and denounce the Republican plan as unhelpful and say its regulation changes are dangerous and will only accelerate the staffing exodus. However, a few in the industry voiced support for the Republicans' bills, stating they valued providers having the option to add more children to their programs should they choose to, and have the specified staffing to do so.

Instead of taking up Evers' special session proposal earlier this month, which sought to include extending Child Care Counts funding, Republicans in the Legislature moved the plan to committee and said they would come back with their own workforce and child care proposals.

More: Republican lawmakers and Evers divided over child care, workforce issues

More: New GOP bills hope to alleviate Wisconsin's child care crisis. But how?

Forward Analytics is not taking a stance on the Republicans' or Democrats' respective plan; however, Dospoy said one thing is clear: “There are options for increasing funding for child care, whether that takes the form of Child Care Counts or something similar or it takes the form of relaxing regulations so child care providers can have more kids in a classroom.

"The bottom line is there needs to be more money for child care facilities to pay their employees and their providers more, and it can’t be one-time funding, it has to be ongoing, predictable, consistent funding.”

Hope Karnopp of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel contributed to this report.

Madison Lammert covers child care and early education across Wisconsin as a Report for America corps member based at The Appleton Post-Crescent. To contact her, email mlammert@gannett.com or call 920-993-7108. Please consider supporting journalism that informs our democracy with a tax-deductible gift to Report for America.

This article originally appeared on Appleton Post-Crescent: Report shows child care dwindling, more expensive than college. What will Wisconsin do about it?