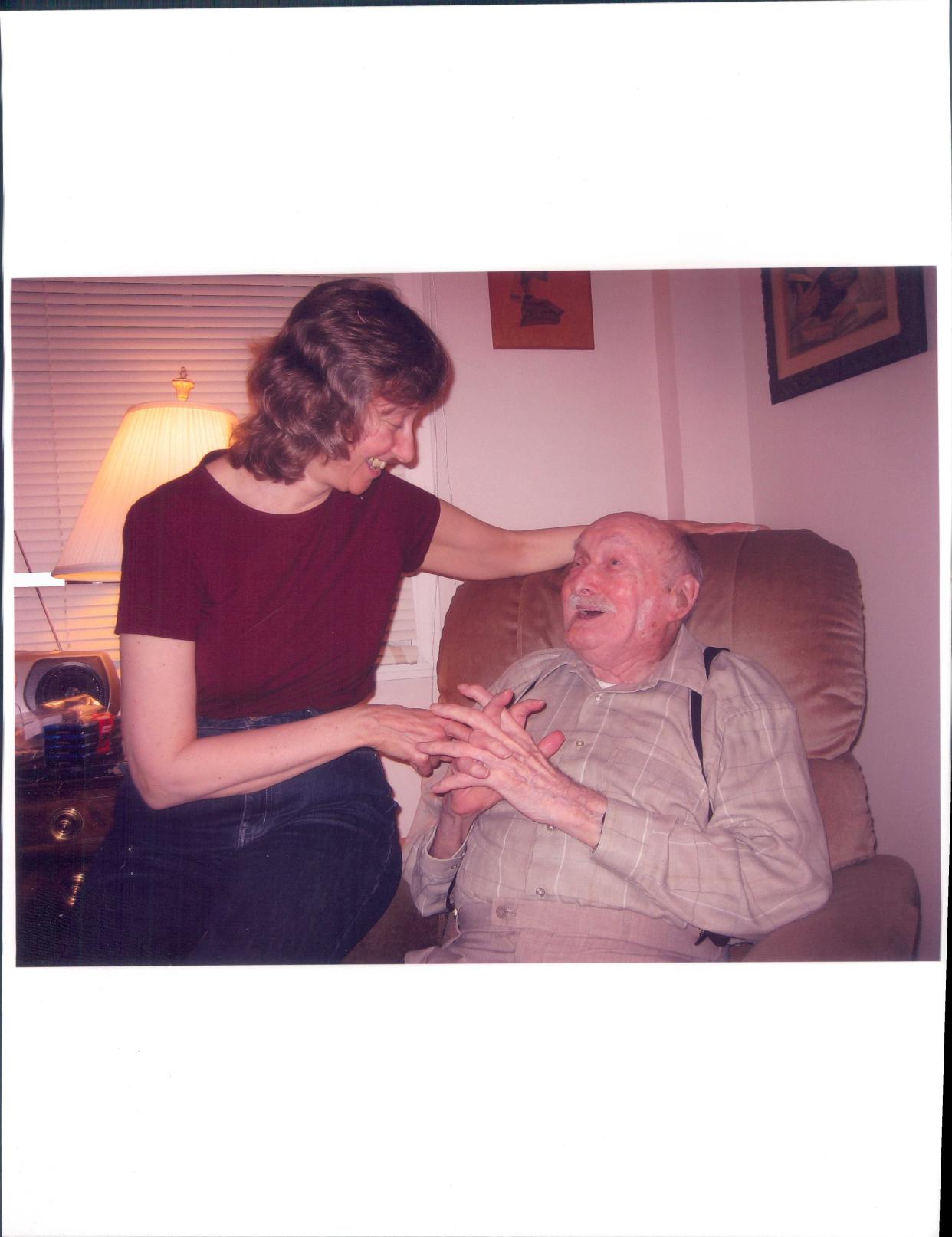

I talk to my father every day, though he died 15 years ago. His voice is lodged in my ears.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When I come across a word whose meaning or pronunciation I’m unsure of, I look it up – and see my father at his desk, reaching for a dictionary, and I thank him for teaching me to care that much about words.

I assure my father I haven’t forgotten the lessons he taught me. When I wash dishes, I hear him saying, about an uncle, “Can you believe Norman lets the water run while he shaves?!” I don’t want my father to talk that way about me, so I soap all the dishes and pile them up soapy, then rinse them all.

My father talks to me every day, too. Sometimes I listen. If I’m about to tear a piece of scotch tape off the dispenser, he reminds me, “You don’t need that much!” I stop and halve the length of tape I take. He also reminds me to shut the light off when I leave a room. And if I hand my husband a knife, I carry it blade down and offer it handle first, as my father tells me I should.

My father speaks through me when I call someone on the phone and begin, “Have I got you at a bad time?”

Who knows best?

Sometimes when I talk to my father, I gloat. I tell him the advice he gave me was wrong, and I did well to ignore it. He urged me to become a teacher, because teachers get summers off, and their workdays end at three. I tell him I would never choose a job because of the time I don’t have to do it.

My father always advised me to do what was practical and cautious. I did become a teacher, but not the type he had in mind. After college, I set off with a plan to travel around the world but got only as far as Greece, where I stayed two years and supported myself teaching English. I fell in love with Greece and learned the language. My father disapproved: I should have chosen a Spanish-speaking country, because Spanish is more useful than Greek.

With a master’s degree in English, I was a teacher of remedial writing at Lehman College in New York when I decided to pursue a PhD in linguistics – clear across the country, at Berkeley! My father was certain I should keep my secure job and get a PhD by taking courses at night, just as he attended law school at night while working days in a coat factory. I explain to him that Berkeley was where I could study the kind of linguistics I wanted to do – how the language of conversation affects people’s lives. And the books I’ve written have helped people, just as my father helped workers by practicing workers’ compensation law. “You see, Daddy?” I say to him. “It worked out pretty well.”

Sometimes I remind my father of the crazy things he said, and he admits they were crazy. After college I moved back to my parents’ house in Brooklyn, so my mail was forwarded there. One day a letter arrived addressed to Jay Lovinger, care of me. My father tells me I made a grave mistake to let a boy receive letters at my address. “Why?” I asked. “Jay isn’t even my boyfriend. He’s my boyfriend’s friend. He stayed with my roommates and me because we had a couch he could sleep on. What harm could the letter do?”

My father explained the potential harm: “You might meet a boy you want to marry, and the postman will tell the boy’s parents that you received a letter addressed to another boy care of you, and they won’t let him marry you.” I was baffled by my father’s reaction, and his logic – or lack thereof. Now it’s obvious to me that he wasn’t talking about a letter; he was talking about virginity. When I reminded him of this decades later, he didn’t remember the incident. “That’s ridiculous,” he said. We both laughed – and we laugh about it together again now.

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this.

My father’s point of view

My father and I have both changed. He concedes that he needn’t have worried about the letter, and I did better to ignore his advice. And I have come to understand that his advice and concern made sense from his point of view.

When he was a young man, in the late 1920’s and early 1930’s, a woman’s virginity was key to her marriageability, and he wasn’t alone in thinking that a woman who didn’t marry was doomed. I see, too, that he had no choice but to keep his day job and earn a professional degree at night because he had to support first his widowed mother and sister, then his wife and children. That’s why he only ever asked what he had to do. He didn’t have the luxury that I had to ask what I want to do.

I think my father is pleased, wherever he is, that I now understand – and appreciate – his perspective. And I think he’s pleased that I learned his lessons about not wasting water, electricity or scotch tape and handling knives safely.

I’m grateful to him for repeating these cautions so often that his voice got lodged in my ears, comforting and reassuring me that my father is still with me, talking and listening, every day.

Deborah Tannen is university professor and professor of linguistics at Georgetown University. Her books include "You Just Don’t Understand" and "Finding My Father," which was published in paperback this month.

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Father's Day: What my father taught me lasted lifetimes – his and mine