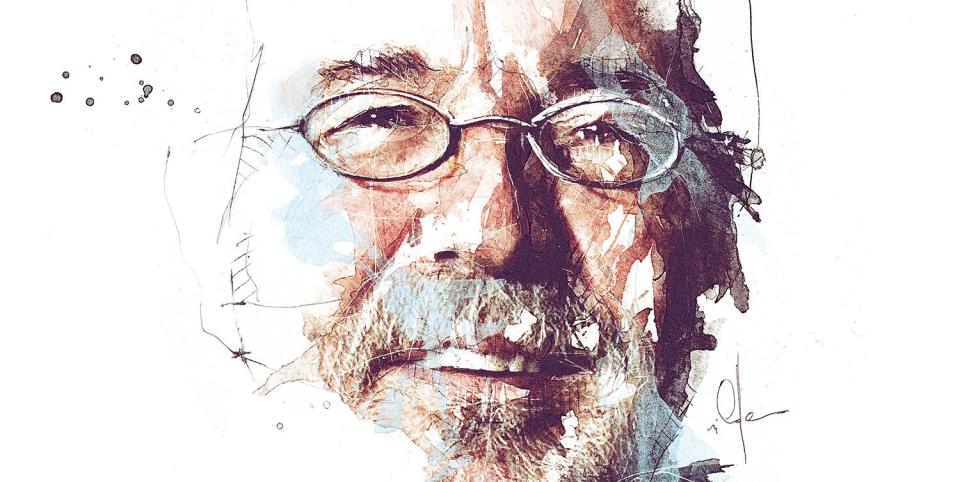

We Talk with Peter Stevens about Being One of Britain's First Car Designers

Car and Driver: Is it true you were one of the first Brits to be formally trained as a car designer?

Peter Stevens: I was doing industrial design at the Royal College of Art, a four-year course. Ford came and said it wanted to sponsor two of us to do a master's degree in automotive design. We were the first in the U.K. It even paid £1200 a year.

So why didn't you spend your working life with Ford?

The deal with Ford was that we would go there afterward. I did bits and pieces, including a terrible facelift of the Capri that I hate. It taught me that I wasn't a Ford man, but also that there's a budget and a timeline for every project, which was the key to the rest of my career.

How did you get to Lotus?

I was working freelance and doing stuff with Tom Walkinshaw Racing. They used a clay-modeling studio near Lotus in Norfolk, and I got friendly with Colin Spooner, the engineering director for the Elan. When Colin Chapman died in 1982, Lotus just stopped. He was the company—nobody even knew how to turn the lights on in the boardroom because Chapman always got there first and the controls were hidden behind a panel. The whole thing atrophied and Spooner asked me to join them because they needed a project to get things moving again. That was the revised Excel.

How did you feel about redoing Giorgetto Giugiaro's landmark Esprit?

There wasn't much of the original left by the time I got to it. It had been through a series of facelifts already, and in my opinion, they got worse and worse.

Your résumé lists the Jaguar XJR-15. How did you fit that between Lotus and McLaren?

It was a squeeze! Tom Walkinshaw and I saw the Jaguar XJ220 at the British motor show in 1988. It had been done by "the Saturday Club," and it didn't look very good. Tom reckoned we could do something better and base it on the Le Mans car, the XJR-8. I'd resigned at Lotus but was working a notice period, so the clay model was driven across in the back of a van, and after finishing work, I'd go and work on it in secret.

How did you get to McLaren?

Gordon Murray got in touch and asked if I knew a designer for a road-car project he was starting. We had a couple of beers and he told me about it, and of course I said, "Yes, I do, and it's me."

Was the F1's three-seat layout already decided?

There was a huge discussion. Ron [Dennis] thought it should be a single-seater, and Gordon said, "You might not have any friends, but other people do." Of course, having three seats across would have made it huge, which is where the tucked-back packaging came from. During the first year, I didn't actually draw anything. I was bursting to, but we had to do aerodynamic stuff first. The middle bit, the passenger compartment, was easy, but the front and rear were the hard parts.

But you don't like the F1 GTR Longtail, do you?

No, I don't. It was no quicker than the short tail, and it would have been much easier to make the short tail more aerodynamic. The LT was dreadfully pitch sensitive because it had this stupid long nose with a flat underside. But I'd left by then, so I can't really complain.

Next you had a very brief stint as Lamborghini's head designer.

It seemed like a good idea at the time. Mike Kimberley, who had been my boss at Lotus, became the managing director at Lamborghini and asked me to be the chief designer. The Diablo SV was done on my watch, but I quickly learned that the company was strikingly divided. It was what Ferrari used to be: trying to beat the guys down the corridor rather than rivals outside. I'd had enough after a year and a half, but they still owed me a huge amount of money. They paid me with shoeboxes full of 1000-lire notes.

You have taught car design for much of your career. How does that compare with doing it?

I enjoy sharing the knowledge, but also introducing students to the idea that they need discipline and a focus. It's not just drawing pretty cars. You have to be creating something with a purpose.

What would you take a mulligan on?

I'd describe myself as somebody who never walks halfway across the road and then changes his mind to go back. That's a sure way of getting run over.

Do you regret being best remembered for supercars?

That's inevitable, the snazzy stuff. I worked with Mahindra and Mahindra in India. We did a little thing called a Gio, a rural utility vehicle, as simple and inexpensive as it could be. When I see a whole bunch of those in India, I think that it has changed many more lives than the McLaren F1. Every single thing you see is designed; it's just well or badly designed.

From the May 2019 issue

('You Might Also Like',)

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos