'Tall, pretty insurance clerk' Patty Tatum was best softball pitcher Indy had ever seen

Editor's note: This story was originally published in 2022. Some references may be out of date.

AVON — Her first team was sponsored by Kingan & Co., Indianapolis' largest meat factory. Then Ban-Dee, a local joint claiming to have the best fried chicken you ever ate, took over. Anchor Tool came next. Then Frosch Bros. got the naming rights to the city softball squad everybody wanted a piece of.

A team with a pitching phenom named Patty Tatum.

Newspaper articles in the 1950s described her as "tall Patty Tatum," "Farm Bureau clerk Patty Tatum," "pretty Patty Tatum." Those articles also went on to reveal the prowess of a 5-11 star on Indianapolis' flourishing softball scene.

With her slingshot pitch, never a windup, Tatum hurled no-hitter after no-hitter. All the while, she carried a .400 batting average. Stadiums would fill with fans at nights and on weekends to watch Tatum play.

More: He was, arguably, Indy's best fastpitch softball hurler ever: 100 mph, a wicked rise ball

She pitched on the women's amateur softball circuit starting when she was just 13. Schools didn't have girls' softball teams in the late 1940s and Tatum wanted to play. So she did.

"They didn't have rules back then," said Tatum, 87, now Patty McDonald. "They didn't have anything. Just play. Anybody could have played."

Tatum played and pitched her way to national tournaments in Florida, California and Milwaukee. She pitched her way to two world series.

And she pitched her way into the USA Softball Hall of Fame.

"I didn't know I was that good," Tatum said. "All the articles I was reading, I read one and I said, 'I did not know I was that good.'"

'Top Hoosier feminine softball hurler'

Tatum is sitting in the kitchen of her Avon home, the same house she has lived in for 62 years. The scrapbooks and trophies and patches from uniforms are spread out on the table.

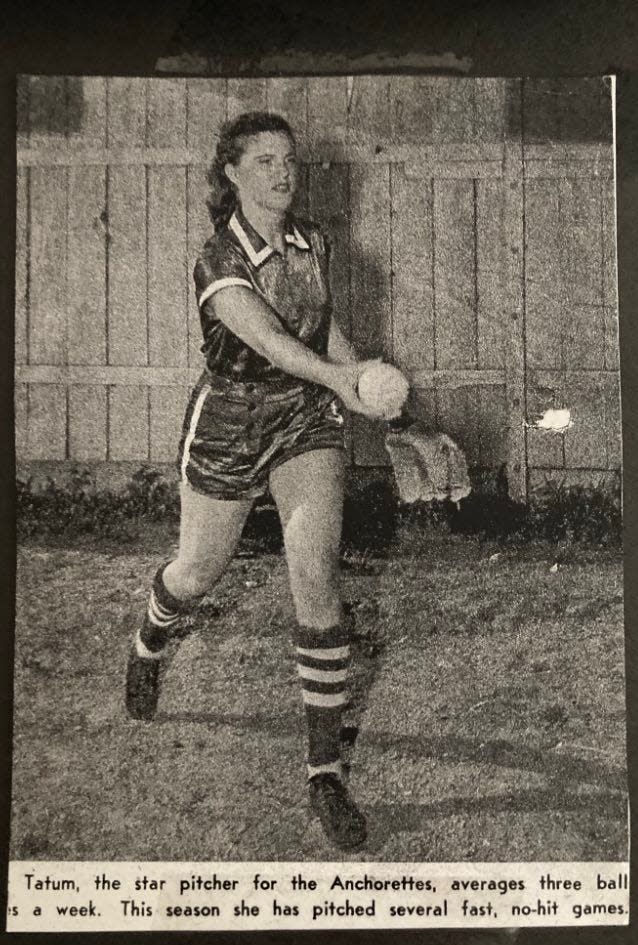

"Patty Tatum, the star pitcher for the Anchorettes, averages three ball games a week. This season, she has pitched several fast, no-hit games," reads the September 1957 Indianapolis Star.

"An Indiana Farm Bureau secretary had a good day yesterday when tall, 19-year-old Patty Tatum pitched and won two games for the Ban-Dee softball champions at Municipal Stadium," the Indianapolis News wrote in July 1953.

"Clerk pitches her third one-hitter. A 20-year-old Indiana Farm Bureau clerk, Patty Tatum, ranks today as the top Hoosier feminine softball hurler," the 1954 article in the Star's sports section proclaimed.

In Tatum's days of being a local star on the mound, she was also a clerk at Farm Bureau Insurance downtown. "It was something I didn't want to do," she said. "But I had to get a job."

So each morning, Tatum headed downtown and took on the tedious work of poring over insurance policies.

But when her shift was over, the tall insurance clerk transformed into the greatest women's softball pitcher the city had ever seen.

'We had a lot of work to do'

She was born in Indianapolis on May 15, 1934, but Tatum's not sure exactly where she was born.

"There wasn't anybody who talked about it. I was probably born at home I imagine," she says laughing. "We never talked about that. I tell my sister that. 'Why didn't we ask mom where we were born at?'"

Tatum was raised in a modest home near Rockville Road with no indoor plumbing and an outhouse.

"We had the ice man, the bread man," she said. "We had our own chickens, own gardens." And Tatum, her brother and three sisters had their own chores.

As a young girl, there was no time for softball. Tatum worked — in the yard, cutting grass, gardening, helping with the chickens and cleaning their coop.

"We had a lot of work to do," she said. "I had to clean the chicken house. I hated that."

But when Tatum was 9, tragedy struck her family. Tatum's older brother was riding his bike when a car pulled out on Rockville Road and fatally struck him. He was 14.

"I still remember that because they had him laid out in the house," she said. "The casket was in the house. I can still see him."

Their son's death hit Jack and Stella Tatum hard — and things changed.

Tatum said her dad had never talked much about his baseball career, playing college at Central Normal in Danville. But after her brother died, grieving the loss of his son, Jack Tatum turned to his four daughters.

And he began pouring himself into teaching his girls the sport he loved so much.

'I pitched all day long' in the backyard

"Get a bucket of balls and go out and pitch," Jack Tatum would tell Patty. He had concocted a backstop for Tatum to throw in the backyard.

"My dad had a big tarp, a great big tarp and I pitched all day long to it," Tatum said. She would pitch any chance she got.

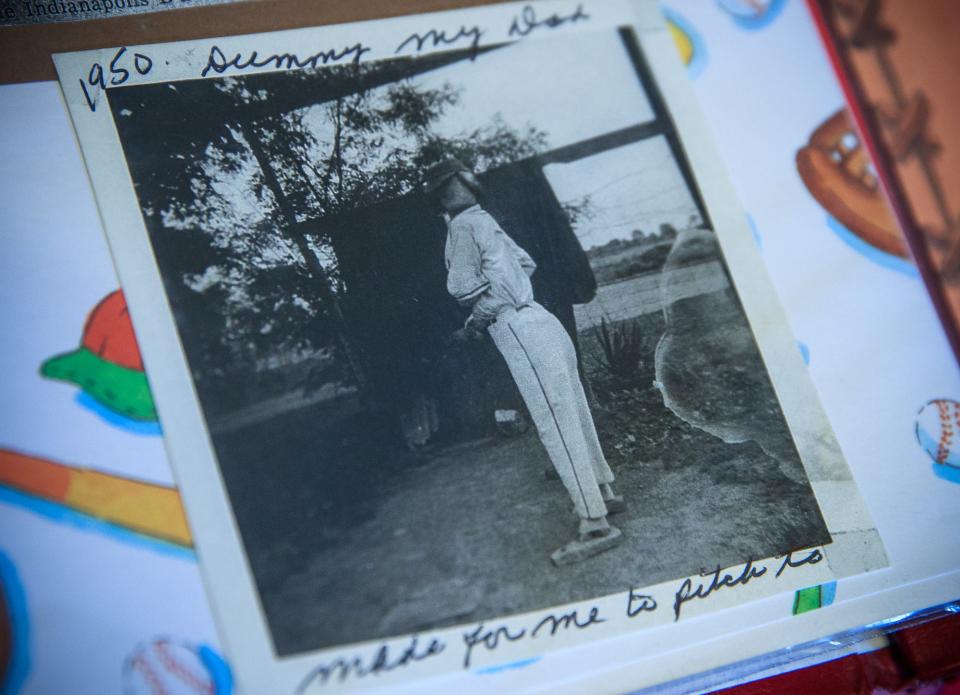

But soon her dad had a better idea. "My dad made me a dummy. See right there?" Tatum says pointing to a photo in her scrapbook.

Jack Tatum built a batter, a wooden batter, to stand in the yard.

"I'd pitch to it instead of someone standing there all day long," Tatum said. "People'd go by and say, 'I saw you.' It wasn't me; it was my dummy."

By the time Tatum was 13, her dad began to notice her talent. Jack and Stella started a softball team in 1948 sponsored by Kingan, the meat factory where Jack Tatum worked.

Tatum still remembers her mom showing up to games in a house dress. Imagine, she said, a coach in a house dress.

But that Kingan team, with her mom and dad coaching and her two younger sisters playing, found remarkable success. Their first team went to Gulf Shores and won nationals.

As the Tatums' team took off, sports writers began to notice. Not only was there Tatum, but her sister Mae played first base and sister Katie was the catcher.

"Jack Tatum should be mighty proud tomorrow..." the Indianapolis Star wrote the day before his three girls took to the field for a big tournament.

But one of those girls regularly stole the show, a 5-11 pitcher. "I didn't see their names in the newspapers like I saw mine," Tatum said. "I don't know why."

'They'd swing before the ball got there'

Tatum said it's hard to remember details of a lot of things that happened more than 70 years ago. But she can remember what it felt like to stand on the mound, in a close game, with the crowds roaring. She can remember exactly what she was thinking.

"Oh, strike them out," Tatum said.

One of her favorite sling shot pitches was a knuckle ball. "Real slow," she said. "They'd swing before the ball got up there. I did that."

Sometimes, she wore a white glove. That made it hard for batters to see the white ball coming out.

It all worked perfectly and Tatum became a local softball celebrity.

But it wasn't always easy being a star. During four years of her career — which spanned from ages 13 to 25 — Tatum attended Ben Davis High School. She played basketball, volleyball, softball and bowled on traveling teams; girls school sports didn't exist.

"That's why nobody liked me at school. I was traveling. I was a loner," Tatum said. "I didn't hang around with people. The boys wouldn't talk to me because I was better than they were. That's what they told me later."

The Ben Davis boys basketball coach even asked Tatum to play for the team. She was known around school as "Goose Tatum," the same nickname of a player with the Harlem Globetrotters.

"I was tall in school. I got made fun of. I got bullied probably," she said. But, Tatum says with a smile, she got the last laugh.

There was one guy who didn't care that Tatum was a tall, standout athlete. His name was Larry McDonald and he was a star softball player on the men's scene.

He wasn't intimidated by Tatum. After all, he was just as good as she was.

Her husband's in hall of fame, too

How Larry McDonald first asked her out, Tatum said, she can't remember exactly. The two had met playing volleyball and then ran into each other at Indy softball stadiums.

McDonald worked for the Indianapolis Star & News. "He was like Dick the Bruiser," said Brian McDonald, the couple's son. "He would pick up (these huge) Sunday sections and drop them off to the substation."

That was McDonald's job by day. But at nights and on weekends, he was one of Indy's best softball pitchers. Ranked among the top five pitchers in Indy for years, he played fast pitch during the days of Indy greats like Jim Stonebraker.

"He used to scare the (crap) out of me when he pitched," said Brian McDonald.

Tatum and McDonald became a dazzling wedded softball duo. In 1960, newspapers started writing about the couple. Both were on Frosch Bros. teams, Tatum pitching for the women, a team "comprised of the city's top players," and McDonald pitching for the men.

"Larry McDonald is considered one of the top prospects in the sport," wrote the Indianapolis Star. "And so is his wife."

McDonald went on to a career that put him in the USA Softball Hall of Fame. He died in 1988 at the age of 51, working the night shift transporting newspapers. He had a heart attack in his car.

By the time Tatum got to Wishard Hospital, her husband was already gone. "He died too soon," she said. "Too soon."

The McDonalds had three children together. Tatum gave up her softball career after having her first son, then a daughter and another son. But McDonald kept playing. Tatum and the kids would go to watch.

"Just like when mom played, the stadium stands were packed," Brian McDonald said. "It was cool back then."

Not many today know about those days of Indianapolis softball mania, Brian said. But they should.

'Never even thought of that'

Tatum blazed a trail for women, showing the world that tall, pretty girls could also be amazing athletes.

"Nope, never even thought of that," said Tatum, when asked if she considered herself a pioneer. "But somebody told me that the other day."

Tatum still gets noticed. Most mornings, she goes to the YMCA and spends 10 minutes or so on a bike that also works out her arms; she's not sure what it's called.

After her workout is finished, people sit down and start talking. "Come on Pat, talk to us," Tatum says they tell her.

She starts talking and, before she knows it, a man is asking for her autograph. The next day, Tatum brings back a softball for him, signed with her accolades as a hall of famer and world champion.

"He acted like that was the best thing he ever had. You ought to have heard him," Tatum said. "He told everybody what he had."

Tatum was inducted into the USA Softball Hall of Fame in 1981, but never really thought about it being a big deal. Now she does. Tatum has two great granddaughters, Ily, 13, and Lila, 9. Both play on elite youth softball teams; Lila is a pitcher.

When they are out at the ball fields, Brian McDonald said, people will point to his granddaughters. "They'll say, 'Did you know her grandma is in the softball hall of fame?'"

Tatum smiles as her son tells that story and then she turns back to her scrapbooks, filled with photos of an era when she was the star. Tatum at softball tournaments in California, Florida and Texas. Tatum at two world series appearances.

And yet, with all her successes laid out in front of her, Tatum still isn't sure how to answer a question about being the best softball pitcher Indy had ever seen.

"I don't know," she said. "I guess you could say that."

Follow IndyStar sports reporter Dana Benbow on Twitter: @DanaBenbow. Reach her via email: dbenbow@indystar.com.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Indianapolis softball's greatest pitcher was insurance clerk in 1950s