Taming a pest: New invasive species to Florida is tiny but deadly to landscapes and crops

Some bugs chew on leaves, others suck out a plant’s juices. The thrips parvispinus scratches the flesh and slurps, scratches and slurps, scratches and slurps.

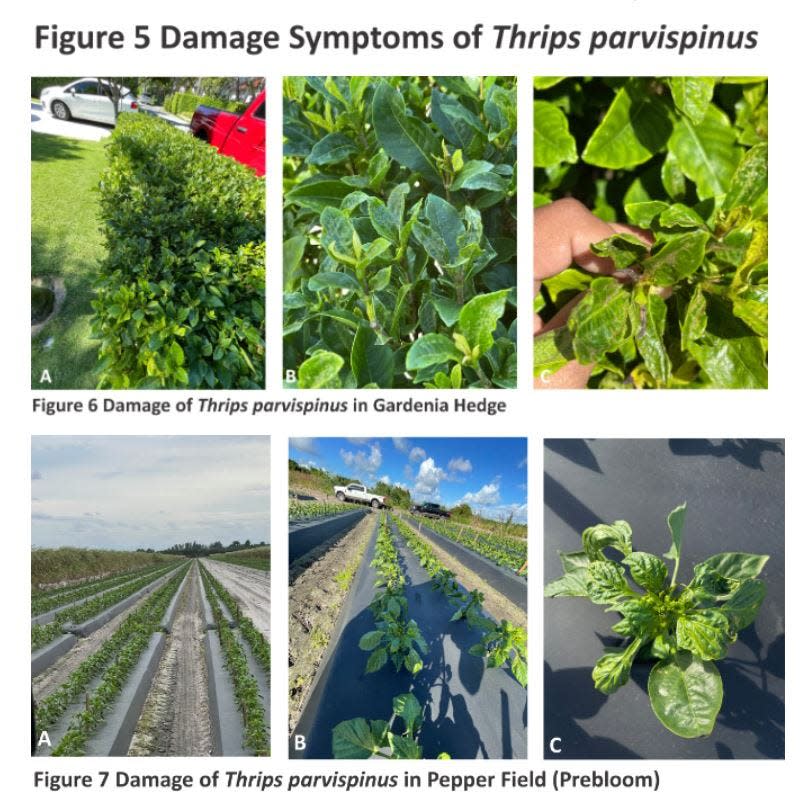

The nearly invisible invader from the Asian tropics was first noticed in Palm Beach County in 2022 by attentive landscapers on tony Palm Beach Island watching their fragrant gardenias and showy rock trumpets desiccate on their stems.

In the rich agricultural soils that grow row crops and commercial ornamental plants, millions of dollars in damage was happening. Peppers were hit especially hard, showing signs of curling leaves, stippling, scabbing and stunted growth when infected.

Growers went on high alert, so did the scientists.

Science of growing plants: UF researchers play major role in Glades area farms’ success

“The farmers didn’t know what was happening at first. It was a mystery, completely new to everyone,” said Anna Meszaros, the commercial vegetable production extension agent working with the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences in Palm Beach County. “It caught us all off guard.”

A scramble ensued to find a fix before this winter’s growing season. Entomologists from UF and the U.S. Department of Agriculture joined forces, set up labs and scoured garden centers for plants infected by the pesticide-resistant menace.

It was a code red, a 10 on the threat scale.

A tiny terror hits Florida’s food crops and flowers

Like all invasives that reach the Sunshine State, the thrips parvispinus seems to flourish in its warm southern reaches but it was first discovered north of Orlando in an Apopka greenhouse in 2020. The fringy-winged insect has since been identified at a garden center in Arvada, Colorado, a Food Lion in Tifton, Georgia, and retail locations in the Carolinas, according to a University of Florida report. It has also been intercepted in Ohio and Pennsylvania.

It's not a picky eater, preferring ornamental plants, but just as likely to gorge on vegetables, fruits, and even tobacco.

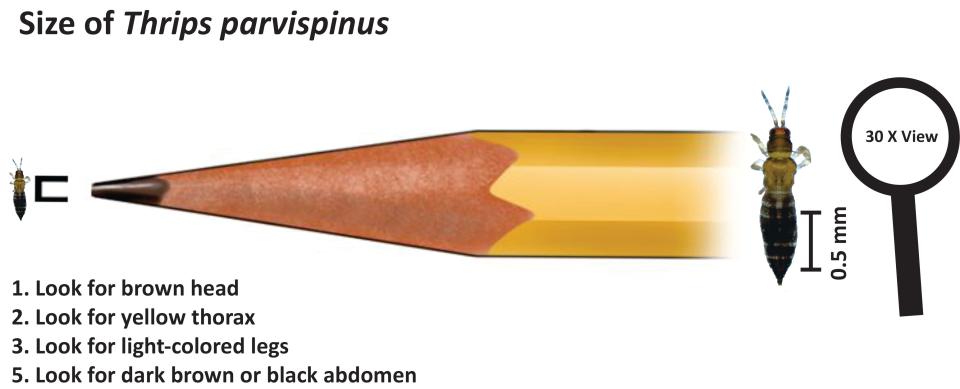

Though the adult female is visible to the naked eye, she’s smaller than a pencil tip. The larvae are transparent, a perfect camouflage.

“It’s very small and it hides very well,” said Muhammad “Zee” Ahmed, a USDA research entomologist who is working on early identification of the thrips. “If you miss them in the early stage, you will have a heavy infestation because they reproduce fast.”

The life cycle of the thrips parvispinus is about two weeks. The female is fertile within nine days, laying about 15 eggs in a clutch.

Because the damage they cause is similar to multiple types of insects and disease-causing pathogens, growers tried to treat them with traditional insecticides that work on other thrips species and mites.

John Roberts, a commercial horticulture specialist focusing on ornamentals at UF’s IFAS in Palm Beach County, said it makes sense that landscapers focusing on high-end gardens were the first to report what was happening as expensive plantings withered.

He was on a team that surveyed garden centers in Palm Beach County searching for the thrips parvispinus. Between 70% and 80% of the centers had them.

And because the insects are labeled a “regulated” pest in the United States, nurseries that have them aren’t allowed to sell the infected plants until the thrips are eradicated, which can be a devastating economic loss. Often, the plants are too badly damaged to sell anyway.

Breeding deadly insects: They’re raising attack insects to destroy invading ferns in Everglades

“It got to be really concerning with the fact that it wasn’t just affecting ornamentals. It was affecting something people eat,” Roberts said.

By the time Meszaros was called out to the farming fields, it was too late. Damage was substantial, in some cases reaching up to $3 million.

“What happened last year was bad,” Meszaros said. “But this year is a completely different story.”

How to kill a killer invasive species

In Homestead, ornamental entomologist Alexandra Revynthi has been busy in her lab trying to find control methods for thrips parvispinus. Despite them being present in at least 17 countries, including India, Indonesia, Japan, Taiwan, Singapore and Thailand, Revynthi said there has been little research done.

“Nobody really expected what happened; that it would be so aggressive toward several different plants,” said Revynthi, an assistant professor at UF’s Tropical Research and Education Center. “They cannot be eradicated. We have passed that stage.”

But Revynthi, along with colleagues, had a landmark study published in January in the journal Insects that provided some early solutions to controlling the invasive thrips.

Out of 32 conventional and 11 biological insecticides, the researchers found a handful that killed or restricted feeding. The conventional insecticides have technical names, such as spinosad and pyridalyl, and are mostly only available to commercial pest control companies. But mineral oil, sesame oil and garlic oil were also found effective, and the study recommends rotating them with traditional insecticides.

The testing is now moving from the lab to the greenhouse.

“It was very worrisome in the beginning, but we are learning how to deal with it,” Roberts said about the invasive thrips.

Unlike the myriad damaging invasive species from giant snakes and giant snails to insidious climbing ferns and canal-choking water lettuce, the thrips parvispinus is tamed, for now — a rare success story in Florida’s endless fight to protect its fragile ecosystem and productive agriculture industry from outsiders.

“We are out in the fields every week monitoring and know what to look for now,” Meszaros said. “I’m optimistic.”

Kimberly Miller is a veteran journalist for The Palm Beach Post, part of the USA Today Network of Florida. She covers real estate and how growth affects South Florida's environment. Subscribe to The Dirt for a weekly real estate roundup. If you have news tips, please send them to kmiller@pbpost.com. Help support our local journalism, subscribe today.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Thrips parvispinus is a costly invasive species in Florida found in 2020