Tapestries Exhibition at the Bechtler Museum of Modern Art Illustrates the Form's Continuing Relevance

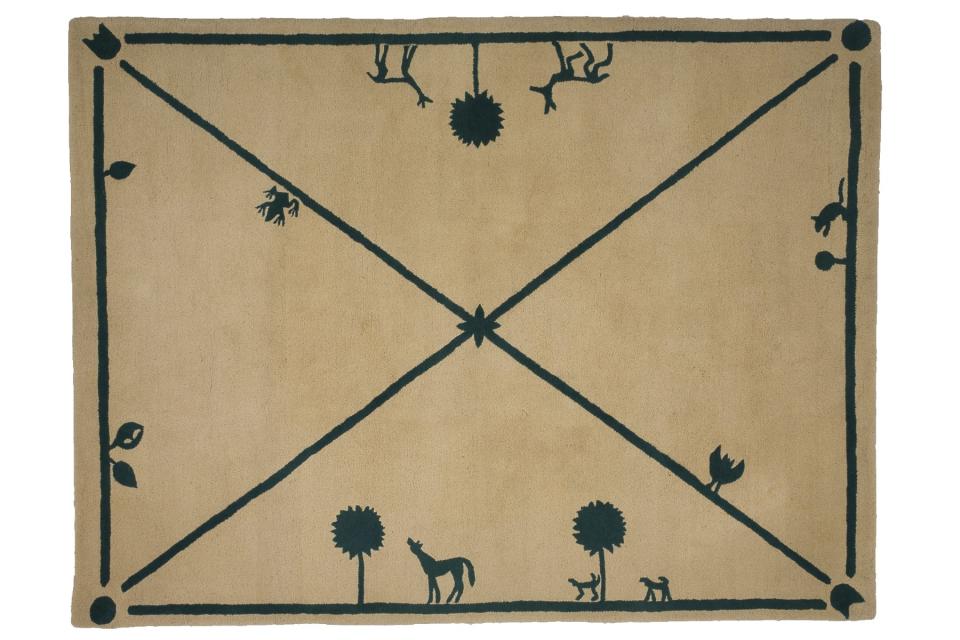

"Everything that we think of as modern today was at one point contemporary," John Boyer, director and curator at the Bechtler Museum of Modern Art in Charlotte, North Carolina, tells AD PRO. "The lines are undoubtably blurry." Nomadic Murals: Tapestries of the Modern Era, an exhibition opening at the museum today, makes that relationship clear, thanks to its 40 tapestries by modern and contemporary makers best known for their work in non-woven media. (Notably, five newly conserved works by Alexander Calder, Diego Giacometti, Fernand Léger, Roy Lichtenstein, and Pablo Picasso are included.) In addition to exploring the visual connections among tapestries across several decades, the show highlights the evolution of production processes and the sweep of approach and subject. Perhaps most interesting, the exhibition demonstrates why designers are continuing to explore the craft today.

Historically, tapestries were a practical necessity as well as a decorative accent, providing warmth and sound dampening to stone-walled homes as early as the 15th century. Because of their high cost, however, they were a status symbol—a luxury item composed of narrative textile images. In the 19th century, according to Boyer, their "functional role shifted to become one of purely aesthetic purpose." When French modernists rediscovered the artistic medium in the 1930s, it was with a more definite use: to amplify the contrast between the latest architectural trend—then-pared-down volumes of the International Style.

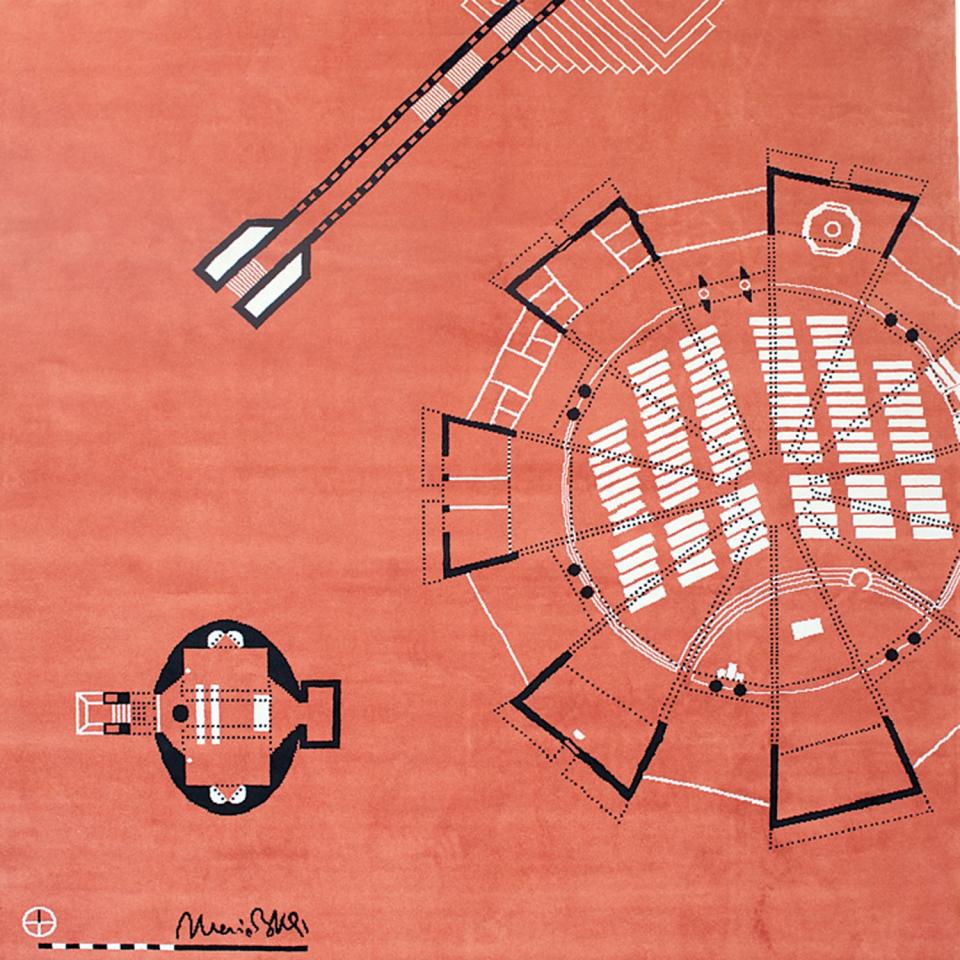

At the time, "a wide variety of artists elected to engage with another medium," Boyer says, citing the modernist Le Corbusier as an example. From his scale-drawing maquette of a tapestry, Le Corbusier would engage professional weavers to finish his design, allowing him to expand his exploration of ideas in a 2D plane. Though historians are quick to silo a designer within his or her most well-known medium, the history of modern tapestries proves that the artistic boundaries between disciplines are far more fluid. Says Boyer, "We should be thinking of people like Le Corbusier not just as a modernist but as a natural extension of the Arts and Crafts movement."

Today, too, designers elect to expand their creative palettes. While visual artist Ebony G. Patterson follows the traditional route of making her mixed-media tapestries by hand (often introducing jewels, objects, and hair as well), artist Jeff Sanders works with Oakland-based printmaking workshop Magnolia Studios to attain photorealistic results via computer algorithms. In the same modernist vein, a contemporary maker's expansion into weaving may require collaboration with craft experts, something Boyer has seen as a "delight and challenge."

Though historically overlooked in the design canon (in some circles, "craft" and "decorative art" are used pejoratively), tapestries are as important as any other visual art. Boyer hopes he has curated a show that is a "reminder of the seriousness in which great artists explored media." As he says, "The artist doesn't differentiate" between tapestry and other art forms, so why should we? As multidisciplinary work grows in popularity, the lines are increasingly blurred between art, design, and what has traditionally been thought of as craft. In the same spirit, within the world of decorative arts, tapestries are as relevant as ever before