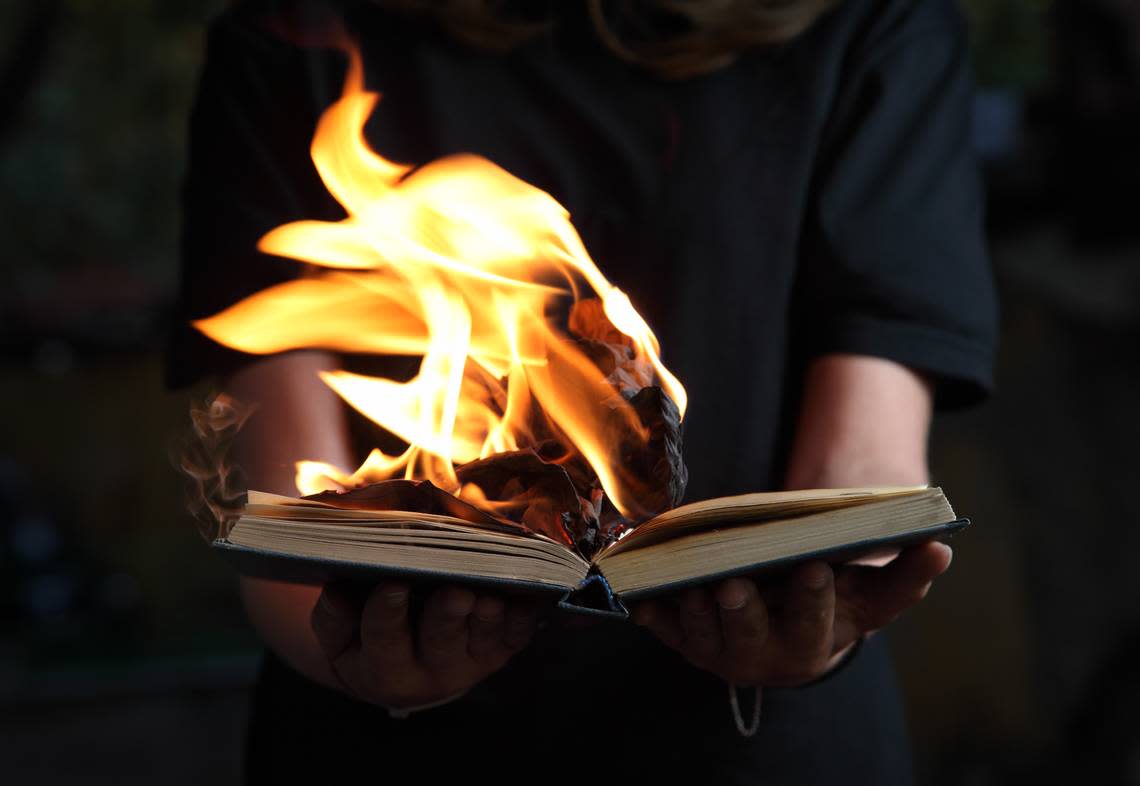

Targeting books is the first perilous step down a slippery slope to more censorship | Opinion

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This week, the national spotlight was once again on Florida — and not just because it was the week when a North Florida congressman named Matt Gaetz, a Donald Trump acolyte, staged a mutiny that ousted of House Speaker Kevin McCarthy.

No, this was more serious. Oct. 1-7 is Banned Books Week, an annual observance in which those on front lines in the defense of freedom sound an alarm about what they perceive as recent trends toward censorship.

Florida’s dubious distinction as the national leader in book bans was mentioned in a National Public Radio story that aired on Sept. 21. Citing a report by the writers group PEN America, NPR reported that “Florida had more bans than any other state.”

NPR’s story also noted that “Overall, PEN America said it found 3,362 cases of book bans, up from 2,532 bans in the 2021-’22 school year,” adding “The organization counts any move that restricts access to a book as a ban, including books removed from classrooms or libraries or both.”

Granted, many Floridians will find this definition of book bans overly broad. The fact that a book is removed from a kindergarten classroom after being deemed inappropriate for very young children does not necessarily mean it has been banned, at least not in the usual sense of the word.

Indeed, such books are widely available online, at chain bookstores such as Barnes & Noble, and at local bookstores such as Miami’s beloved Books & Books, which this week featured displays and events related to Banned Book Week.

So, if banned books are widely available, what’s the big deal? It’s this: There’ a legitimate concern that targeting books that allegedly corrupt the young could be just the first step down a slippery slope toward more censorship.

There are numerous precedents in many different societies for this kind of creeping censorship where the first steps are taken “to protect the young.” An extreme example was the topic of a Monday lecture by Dr. Monte Finkelstein at Temple Israel in Tallahassee.

A historian of the Holocaust, Finkelstein outlined the evolution of censorship in Germany prior to World War II. Book bans, the persecution of authors and ceremonial book burnings enabled the Nazis to stifle free speech and manipulate public opinion so that when the stage was set for the mass genocide of the Holocaust, there was no one left to protest.

Moreover, as Finkelstein noted, it did not begin with the Nazis. Germany’s initial crackdown on the freedom to read occurred during the Weimar Republic’s brief reign prior to the Nazis’ ascent to power.

With the nominally democratic Weimar regime beset by public complaints about hyperinflation and other economic problems, it imposed regulations “to protect the morals of youth from filth.” Under the Nazis, of course, the regulations were tightened to ban any material the regime disliked.

Granted, nobody is going to believe that the kind of censorship that occurred in Nazi Germany could possibly happen in the United States. After all, we are assured that the First Amendment protects us.

Then again, in Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 novel “It Can’t Happen Here,” it did happen here after the economic woes of the 1930s led to a rise in fascist populism. That was fiction, but the current rise in right-wing populism is a troubling fact and, as Mitt Romney recently pointed out, the movement includes extremists who do not really believe in the Constitution.

Moreover, even within the United States, there are precedents for heavy-handed censorship. Some of the worst occurred during the “Red Scare” after World War II, when the West’s Cold War with the Soviet Union led to a political climate in which dissent was too often equated with disloyalty.

It’s a reminder that one technique national governments sometimes use to stifle dissent is to posit that the nation is facing some kind of dire threat from a foreign power and, thus, the people must rally behind the regime. Will paranoia about China now fill the villain role once played by the USSR?

Inciting fears of a foreign rival is but one of the justifications that governments use to justify forms of censorship. Protecting children — and adults — from depictions of sex is another common rationale.

Indeed, in the decade following publication of Lewis’ book, state and local governments in many parts of the United States censored books, magazines, plays, radio, TV and movies — especially movies — over concerns about their sexual content.

As the American Civil Liberties Union’s 1954-55 annual report pointed out, “Three states (Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania) and 60 cities have official censorship with full administrative paraphernalia.”

Meanwhile, in many other jurisdictions, police frequently pre-screened and banned movies they deemed immoral. Often, they relied on lists supplied by various religious denominations.

When it came to books, the censors in that era had a powerful ally in the federal government. Postal inspectors could decide which books could be legally sent through the mail, and violators were prosecuted.

In those days, much public attention was focused on comic books, which the censors claimed were corrupting America’s youth and contributing to a surge in juvenile delinquency. Now the would-be censors are turning their attention to the role of the internet and social media as corrupters of youth.

All these disparate events — book bans in Florida, book burnings decades ago in Nazi Germany, book and movie censorship in the America of the 1950s — may seem totally unrelated to each other, and so they are.

Nonetheless, taken together they are troubling examples of the kinds of threads that could be knitted together to produce a cloak concealing an authoritarian leader’s quest for absolute power.

That’s a scenario that we cannot allow to happen here.