Task force looking for ways to ramp up Oregon housing says cutting down trees could help

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

As Oregon tries to ramp up housing construction to meet demand, an advisory council established by Gov. Tina Kotek is working on a proposal to loosen restrictions some communities have in place to protect tree canopies.

The governor charged her Housing Production Advisory Council with coming up with solutions to increase production of housing by 36,000 units a year for the next decade.

Among some two dozen ideas, the council has drafted a proposal that says: "No city or jurisdiction shall have a tree code that prohibits or charges a fee for the removal of a tree less than 60″ in diameter."

Cities or jurisdictions also would be required to offer a program allowing for replacement of trees larger than 60″ in diameter, or a fee "when the replacement tree option is not feasible.”

“The whole point is to figure out ways to reduce barriers to increase production of housing,” said Natalie Janney, vice president of WesTech Engineering and a Kotek appointee on the council.

"A lot of people think ... we should be able to provide housing and keep all the trees, but that’s not possible,” Janney said.

Oregon's housing crisis

On Kotek's first full day in office, she declared a state of emergency due to homelessness and established a goal of adding 360,000 homes - single family, apartments, condominiums - in 10 years.

“I set this target to reflect the level of the need that exists, knowing that we will not get there overnight, or even in one year. But we will ramp up over time,” Kotek said.

In 2022, Oregon approved the building permits for 20,404 housing units.

The state needs an additional 554,691 homes over the next 20 years to meet demand, and 176,300 of them need to be affordable for those earning less than 60% of area median income, according to the Oregon Housing Needs Analysis published in December 2022.

The number of housing permits statewide dropped to 12,637 between January and August 2023, compared to 13,778 for the same period the year before, according to HUD data.

Kotek's office formed the 25-person housing production advisory council to provide recommendations to increase the state’s housing production by 36,000 units per year.

The council has come up with about two dozen recommendations including using state-owned land for building housing, creating wetland mitigation “banks” with credits for builders, streamlining the building permit approval process, making it easier for cities to increase their urban growth boundaries, and looking at tree codes.

Natalie Janney, a member of the work group, said the tree proposal next will receive a public hearing, though it's not clear when.

From there the work group will decide if it will pass it on to the state legislature.

Oregon tree codes in Oregon's most populous cities

Each of Oregon's 10 most populous cities have codes protecting existing trees on property to be developed. How strict these codes are varies. The codes below are abbreviated.

City | Code |

Protects trees with 12" diameters. | |

Has exceptions for housing. | |

Protects trees with 30" diameters. | |

Protects trees with 8" diameters. | |

Protects trees with 8" diameters. | |

Has exceptions for housing, streets and utilities. | |

Has exceptions for middle housing and ADUs. | |

Only applies to trees on public property. | |

Allows removal of five trees without a permit. | |

Protects trees in certain areas. |

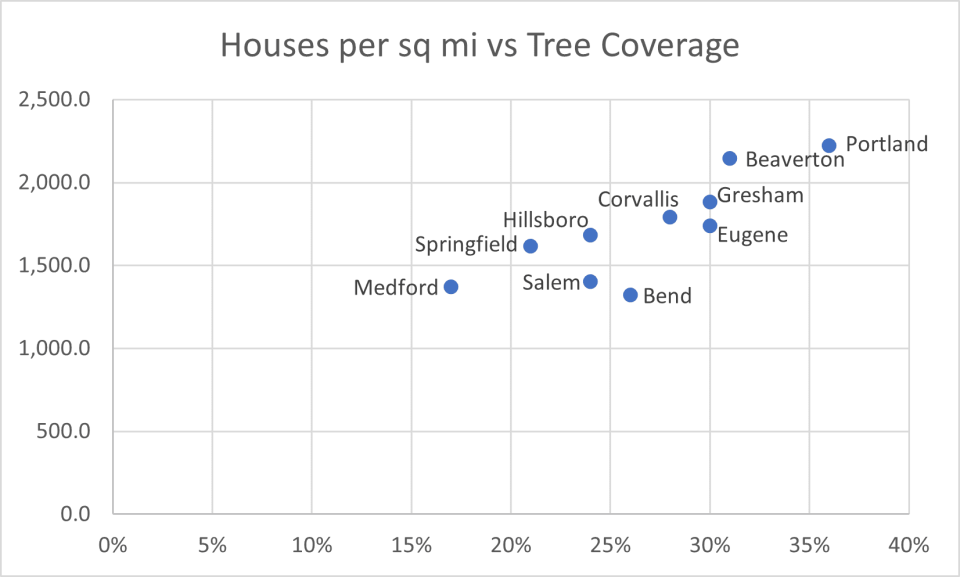

Many of the cities with the highest density of housing also have the highest density of trees.

Eugene already has an exception similar to what the council has proposed. Lots under 20,000 square feet are exempt from tree codes if the lot has or will have a single-family home, middle housing or ADU.

In previous fights between housing development and tree preservation in Eugene, development has usually won. Such as in 2021 when the city approved the 94-unit market rate Velo Apartment complex.

"We prevailed because we're working within the confines of what the code calls for on the site," the developer, Andrew Brand, told the Register-Guard at the time.

The council proposal would override Salem's 2022 tree code that says developers and builders must get permission to remove any white oaks more than 24 inches in diameter and Douglas firs more than 30 inches in diameter. The ordinance also requires developers to protect 30% of the roots of existing trees.

Developers say that most of the developable land inside Salem’s urban growth boundary is in south and West Salem where older trees are one of the things that make the areas more expensive to develop.

"With the tree protections that Salem has many of those parcels are economically undevelopable,” said Mike Erdmann, CEO of the Home Builders Association of Marion & Polk Counties.

“The trouble is because of these tree protections, we have a lot of parcels that really can’t be developed, and that’s the challenge that as an industry we run up against,” Erdmann said.

Developers and builders say it's more cost effective to remove problem trees and plant new ones.

"Obviously trees are an amenity, Erdmann said. And as much as possible we want to incorporate trees into developments because they really do add to the neighborhood."

Environmental justice

Yashar Vasef, executive director of Friends of Trees, an Oregon-based nonprofit that has planted nearly 1 million trees, said the governor's task force lacks environmental perspective.

He and other environmental groups are critical there are no members of the group with an environmental justice prospective, Yasef said.

“It’s an odd avenue to go down because I haven’t seen any evidence, that trees are a primary reason why we have a housing crisis,” he said.

Neighborhoods in cities where income is lower and diversity is higher have fewer trees than high income neighborhoods, according to a study by the U.S. Forest Service.

That study shows the lower income areas are nearly three degrees hotter than high income areas.

Vasef said a federal study conducted in Portland showed that trees that are 15 years old and older offer the biggest benefits in terms of things like the shade canopy, carbon sequestration and other environmental benefits that trees provide.

“If you take enough of those trees away, you create a pretty drastic public health environment there and that’s where I am concerned about what’s being proposed through that council,” Vasef said.

He points to a study of the June 2021 deadly Pacific Northwest heat dome that found the highest death rates in Multnomah County were in areas with the fewest trees.

“It’s disappointing because our position is that we don’t feel that housing and green infrastructure should be pinned against one another,” Vasef said.

Bill Poehler covers Marion and Polk County for the Statesman Journal. Contact him at bpoehler@StatesmanJournal.com

Alan Torres covers local government for The Register-Guard. He can be reached at atorres@registerguard.com or on twitter @alanfryetorres

This article originally appeared on Salem Statesman Journal: Task force says cutting down trees could help ramp up Oregon housing