I Taught the AP Class Ron DeSantis Gutted. He Can’t Shake This Racist Shooting.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

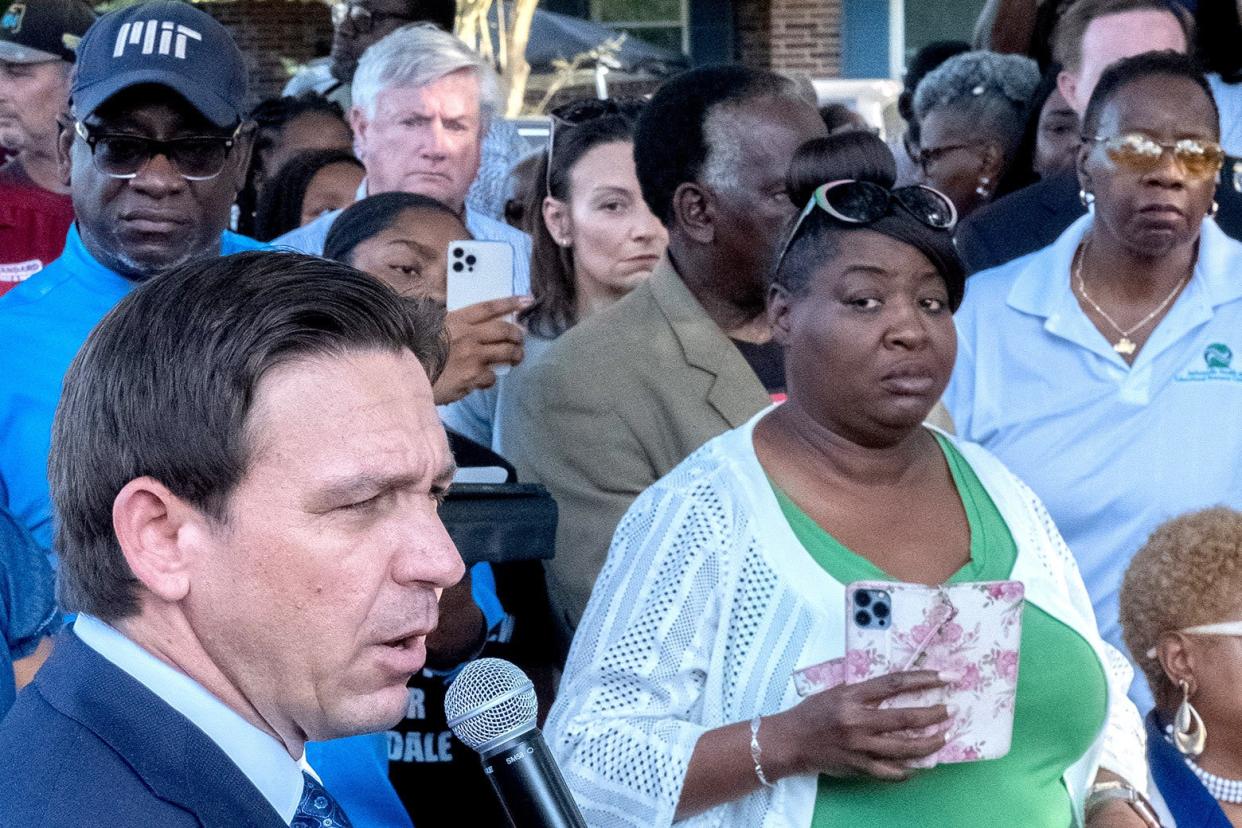

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis was jeered and booed this week at a prayer vigil for those killed and wounded by a racist mass shooter in Jacksonville, Florida. In the middle of his speech, Councilwoman Ju’Coby Pittman grabbed the microphone and scolded the crowd for the disruptive behavior. “It ain’t about parties today. A bullet don’t know a party,” she said.

But for many, there is a connection between the views of the gunman—who killed three Black people at a Dollar General after first stopping at the campus of the historically Black Edward Waters University—and DeSantis’ vehement crusades against “wokeness” and the teaching of African American history in public schools.

Marlon Williams-Clark, a high school history teacher and lifelong Floridian, wasn’t surprised by the reaction to the governor at the vigil. Williams-Clark—known affectionately by his students as “Mr. WC”—was one of only 60 educators in the country who were pioneering a new AP African American studies course, which aimed to comprehensively explore Black history, until his class was suddenly and unexpectedly canceled after the AP curriculum became a target for political controversy. In January, DeSantis’ Department of Education published a letter that said, “The content of this course is inexplicably contrary to Florida law and significantly lacks educational value” and that suggested that the curriculum was illegal, citing concerns of ideological indoctrination.

In an interview, Williams-Clark spoke about that pivotal moment, whether or not DeSantis’ concerns have any merit, and how he considers current events as he continues to teach his students about African American history in Florida. He made explicit that he was expressing only his own opinions and not those of any organization he is connected to. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Aymann Ismail: How did you become one of only 60 teachers across the country piloting the AP African American studies course?

Marlon Williams-Clark: Well, I was one of 60 in the pilot year. Now, in Year 2, there are over 800 schools that offer the course, and they still have not reinstated that course in my state. African American history is something I’ve always been passionate about. I’ve always included it in my curriculum, no matter what history I was teaching. When teaching world history, I went more into African history than a lot of teachers who focused on Rome and Greece.

Can you describe what you taught in your AP African American studies course?

In a larger sense, a deeper understanding of our democracy. When we look at the African American experience post-slavery, every time America has gotten ready to eat itself, Black people have been there to try to help save it. Where there was the Civil War, Black soldiers volunteered in enormous numbers to fight with the Union army. The Civil Rights Movement pushed this country to be the country that it said it was. Before America was America, Black people were here. In 1619 the first 20 or so Africans came into Jamestown, and we’ve been here ever since. Every single war America has ever fought, Black people have been involved in.

The students that took the class were ravenous for that information. They were so willing and ready to engage with that knowledge. I call my classroom a “brave space” so that we could talk out any differences or disagreements and try to understand each other’s perspectives. My students were able to do something that our own governor and education commissioner seem not to be able to do.

What exactly is a “brave space”?

A lot of teachers will say, “This is a safe space.” And I tell my students, “I can’t offer you a safe space.” I say, “We’re going to talk about some hard stuff that might trigger you. And once you’re triggered, that’s no longer a safe space. But this is a brave space to engage with the information, to be inquisitive and ask questions.”

What was your reaction after you first heard DeSantis liken what you were teaching to indoctrination and “a political agenda”?

It was surprise. I was shocked. On Jan. 25, when the article came out that the course was being banned, there was no communication or heads-up from the Department of Education or anything. It caught the College Board off guard as well. I’m not gonna lie: My first emotion was anger. For a politician to call that course indoctrination is disrespectful. And then after hearing their justification and seeing the graphic put out explaining why they were banning the course, I felt insulted. That graphic showed lessons that weren’t even in the curriculum that was given to teachers to pilot. So, I’m guessing they took some old information while the course was still being developed to attack “critical race theory” (which they still can’t define) and make a political play out of it.

You had zero heads-up?

We were in the middle of the course when that came out. My students were upset. I was upset. There was no follow-up. No direction. It was poor leadership to make such a decision. And now they’ve come back with these Florida standards for African American history in which they did not consult any real scholars in the field. Instead, they turned to politically appointed people in a commission that was created in 1994 to ensure that African American history includes teaching that, for example, slaves benefited from slavery. Which is just false. And the way that they try to justify it is to say that slaves gained skills through slavery. No. If we were teaching real history, we would know that Europeans were going to certain parts of Africa because of certain skills that African people had that they needed in order to make their plantations thrive.

What happened next?

I got a lot of support. Other pilot teachers were checking in on me and talked about connecting what was happening in Florida to direct lessons in their AP African American studies courses, and how, to borrow from Colin Kaepernick’s new anthology, Black history has always been contraband in America.

The governor’s slogan is literally “Florida is where woke goes to die.” How do you view your role as an educator in addressing current events with your students?

I try not to. However, when it comes to learning African American history, my students can’t help but see the connections. They ask questions, and in order to protect my butt, I allow them to have those conversations without giving any opinion. I just try and cultivate a conversation where they can have an intelligent dialogue about the matter. But I keep my opinion out of it.

Did you discuss with your students the recent racially motivated shooting in Jacksonville?

We talked about it a little bit. But also, the hurricane has been dominating the news as well, and so naturally they just want to know if they’re going to be out of school. The shooter’s first target was Edward Waters University, which is a historically Black college. And I have two former students that go there too, so it got very real for us. We didn’t talk about it too much, but my students do connect racial violence to lessons of the past. Students are not dumb. It just seems like our politicians want them to be.

Some people have already connected the Jacksonville shooting to DeSantis. Do you have any problem with that connection?

I think it speaks for itself. Look at the laws that have been signed, and look how that might be encouraging to people who have anti-Black attitudes. Look at the video of DeSantis speaking in Jacksonville. The amount of boos and side-eyes that he received … I think it all speaks for itself.

Politicians are acting oblivious, as if their words and the policies aren’t encouraging that kind of behavior. It seems to me that the leaders of our state are very much anti-Black, no matter how much they try to mask it. Their policies and speech are anti-Black, which is why the NAACP issued a travel warning for any Black people coming to Florida. Even the “Stop WOKE” Act … “Stay woke” was Black vernacular from the early 20th century, which Black people have used as a way of warning others what’s happening around them in their community. Because, as we know, just being Black in some areas was a crime.

DeSantis is doing some really hard damage to our state and educational system. We still don’t have the AP course back, even after modifications from the College Board. It’s funny to me that they were about to ban the AP psychology course right before school started again, but then quickly reversed it when there was an outcry about it. But there was a whole march and outcry and complaining and meetings and letters and so many other things about the AP American studies course. So, it seems to me that the government of Florida right now is very much anti-Black.

Do you see any merit to the conservative concern that teaching the nation’s dark past can lead to disillusionment and cynicism?

Our governor is quoted on camera saying that white kids should not feel uncomfortable learning about history. History is not supposed to be comfortable for anybody. History is history. We go with the facts. We go with what happened, and we listen to the voices of the past. We look at primary sources. It is not to make anybody feel bad. It is to teach us so that we don’t repeat bad behaviors of the past. And there is a certain element of our country that is hellbent on making sure that we don’t tell those truths.

It seems that we have many politicians—I won’t call them government leaders—that are okay with a dumbed-down electorate. And that’s not good for any of us. Denying history from being taught is quite insulting to the people that are still living that have experienced these things in real time. We are truly codifying white supremacy, in my opinion, and I think we’re better than that.

It’s got to be interesting teaching African American history while it seems that history is still unfolding around us. Can you walk me through how you think about current events in the context of your classroom?

I think we can learn more about current events through teaching history. For instance, when we look at organizations like Moms for Liberty and what they’re trying to do with controlling curricula and the way we talk about slavery, we can learn a lot by teaching about the Daughters of the Confederacy, who did the same thing in the early 20th century by changing the narrative about slavery in school textbooks. The whole idea that slaves were happy in their condition and they loved their masters—none of that was coming from African Americans who had been enslaved. Or the narrative about how the Civil War wasn’t about slavery; it was about states’ rights. If we just get back to basics and reading and look at the manifestos of the Confederate states, they were very explicit about upholding white supremacy. That was the states’ rights they wanted to have! They did these wordplays like calling it the War of Northern Aggression instead of the Civil War. And my kids are smart enough to see that they’re doing the same thing now.

There are recordings from the 1930s and 1940s of people who were enslaved. There’s one man—I can’t remember his name, but he said, “If I had to go back into slavery, I’d take a gun and shoot myself.” So, for people to act like slavery wasn’t that bad, like “It’s an economic system and yada yada ya,” is just very disingenuous and untruthful. I don’t care what they truly believe. There’s way too much information out there for people to be that ignorant.

As a lifelong Floridian, you had a front-row seat to watch your state go from a swing state to a Republican stronghold. Has that played a role in your classroom? What have you learned from teaching African American history to kids from conservative families?

My biggest strength as a teacher is my ability to build relationships. I’ve never really had an issue with students or difference of political opinions because all my students know that I love them and that I’m coming from a solid place with them. They know they’re not going to be disrespected. And regardless of whether they know my opinion about something or not, they know that I’m not going to disrespect their opinions. I might challenge them with questions to get them to think deeper and more about what they’re saying. But I always tell my students, “You believe what you want to believe, but you have to be able to defend it.” You have to be able to stand 10 toes down and be able to explain it to someone else. So, I’m just trying to push these kids to be competent people that can look at all sides of an argument or situation and form an intelligent opinion. It doesn’t seem to be what my state wants, even though they say that’s what they want. The only indoctrination that’s happening in Florida is coming from the state government.

As your students progress through the AP African American studies course and beyond, what outcomes do you hope to see in terms of their understanding of the societal issues that continue to unfold around them?

We have to be very honest about the policies and the social norms that were in place in the past, because they shaped the attitudes of today. If you are speaking some truth about race issues in this country, some people want to call that liberal indoctrination. There is nothing about my skin color that’s liberal or conservative. And I tell people, there is no particular way that you can be to escape the anti-Blackness that exists in our society. Because before anybody knows that you are a Christian, Muslim, liberal, conservative, or part of the LGBTQ+ community, they see your skin color first. And we have to address that. And we address it by teaching real history about how we came to these attitudes in the first place.

And people might say, “Well, I didn’t have anything to do with that, blah, blah, blah. That was so long ago.” To give my students a sense of how close we are to slavery in respect to time, I tell them the story about my great-great-grandparents, who were born into slavery. My great-great-grandfather died in 1919. My great-great-grandmother died in 1940. So, I ask them, “You know what that means, that she died in 1940? That means that my grandmother and her siblings lived with someone who was once enslaved.” That personal story definitely gives my students some clarification. We’ve got to tell it like that for people to understand. They see black-and-white video and pictures from the Civil Rights Movement. Those people are still alive! They’re banning books by Ruby Bridges? Ruby Bridges is in her 60s! You know what I’m saying?

It is very insulting and sad that there is no shame on the part of people that are trying to change the narrative of what really happened. We have photos. We have interviews. We have slave narratives and novels that tell us the real experience of slavery, which was psychological, physical, mental, and emotional abuse of one group of people. History is a beautiful, ugly story. You’ve got to teach all of it. Teaching only one side does us a disservice, and creates a misconception of what our country is and stands for. But it also creates a misconception about Black people themselves. And as D.L. Hughley said, “The worst place for a Black person to be is in the imagination of white people.” A lack of understanding creates dangerous attitudes towards Black people.

I love that you just quoted D.L. Hughley. … We talked a lot about how to make white students less uncomfortable with African American history. But can we talk for a second about what Black students in particular have to gain from learning this history?

By learning about your legacy and where you come from, you gain a sense of self and empowerment. Like finding out your own family history, understanding where we come from, what existed, what laws were in place and how that affected different groups of people, we gain a more understanding society, and a more intelligent electorate, making it less easy for politicians who mean to do harm. Everybody has things in their family that they don’t want to talk about. But because it’s not talked about, at some point in time, that secret comes to the surface and it blows stuff up. Honestly—and this might sound corny—but as the preamble of the Constitution says, “in order to form a more perfect union.” The Founding Fathers were not perfect. They put a pretty good document together for a government which was revolutionary at that time, but they were not perfect. I think they also understood that they weren’t perfect and that what they were starting with wasn’t perfect. That’s why they included those words, “In order to form a more perfect union.” And that says to us that it is continuous work to give everyone the ability to experience America in an equitable and equal way.

It seems to be a very hard concept for many people to understand two and three and four and five things can be true all at the same time. If we teach history in its entirety and authentically, we’ll understand that there is not just one story of American history.

What, in your mind, needs to change first?

Parents need to show up and get active. You got to put the pressure on. Pay attention to what your kids are learning in school. Just as one group of people are trying to control the curriculum in place, you have to show up and get active as parents that want their children to learn true, authentic African American history—the good, the bad, and the ugly. Put that pressure on your schools, your principals, your teachers, your school districts, your states. Because, at the end of the day, it’s our tax dollars that are funding hatred. And we cannot afford that.