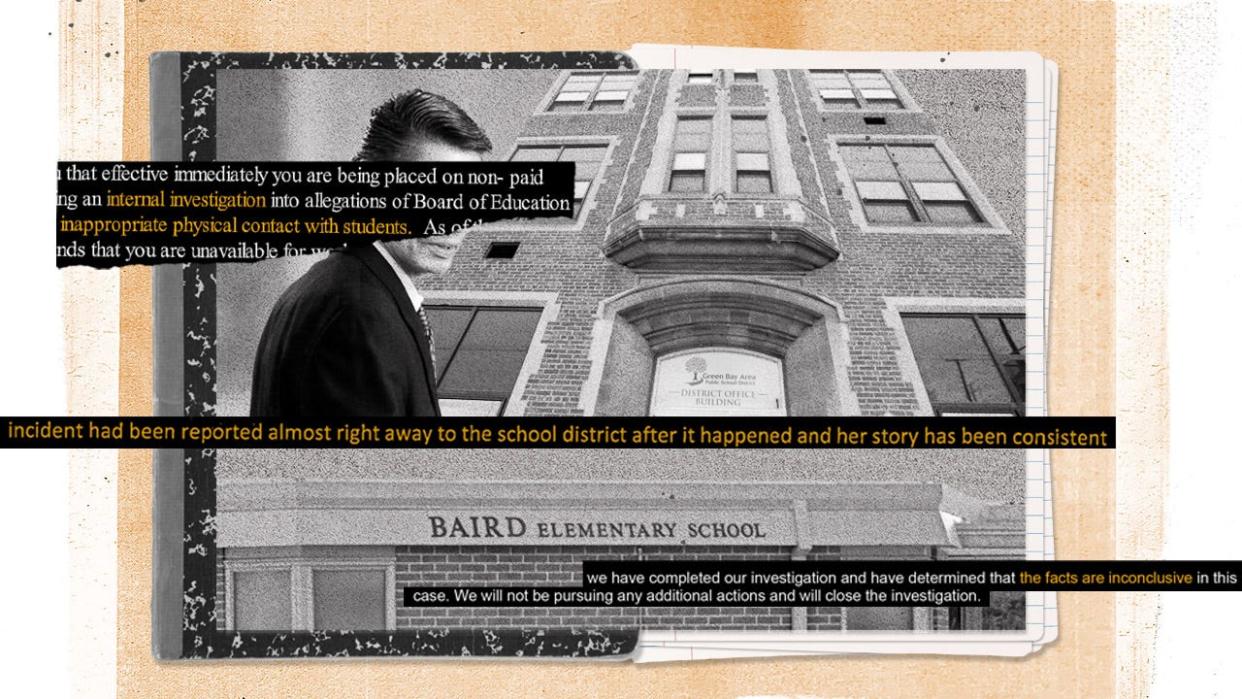

A teacher, a sexual abuse allegation and a botched investigation: '4 lives altered forever' by David Villareal in Green Bay School District

Editor’s note: This article contains descriptions of child sexual abuse that some readers may find disturbing.

GREEN BAY - Every day, David Villareal would have lunch in his classroom with a small group of his female second-grade students. The lights were usually off, and they were alone.

In his mind, these lunches were “dates.” He would give the girls toys, trinkets and candy, asking them not to tell anyone, a student later testified.

At Baird Elementary School in Green Bay, he wanted to be known as the cool teacher, the funny teacher. He volunteered in an after-school running club, and he taught summer school in Sheboygan, where he lived.

Then, in January 2017, the mother of one of his students told the principal Villareal touched her daughter's "private parts."

The Green Bay Press-Gazette found that, instead of conducting a thorough inquiry into the allegation, the Green Bay School District botched an investigation and kept Villareal in the classroom — until another girl came forward four years later.

Experts say these missteps included asking the child to recount what happened in front of Villareal and closing the investigation without interviewing other students.

The Press-Gazette also found gaps in the county's child welfare system and state reporting laws that kept the extent of Villareal’s abuse in the dark.

Because Brown County Child Protection Services failed to notify police about the girl’s allegation, police didn't investigate her complaint at the time.

A loophole in state law also meant the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, which had the power to conduct its own investigation and revoke Villareal's teaching license, wasn’t notified.

In an email to the Press-Gazette, the Green Bay School District defended its actions, saying that it "promptly conducted” an investigation and “screened out” the complaint as not violating Title IX, according to spokesperson Lori Blakeslee. Title IX is the federal civil rights law protecting students from sexual abuse and harassment at federally funded schools.

The district followed its obligations under state and federal law, according to Blakeslee. The district denied the Press-Gazette’s multiple requests to interview staff and didn’t answer questions about case specifics.

Four Title IX attorneys who reviewed the case said the district should have conducted a Title IX investigation. At the time, that would have required the district to share the outcome of its inquiry with Villareal and the mother and give them a chance to present evidence.

"They did a very botched investigation. I wouldn't say even a fair investigation,” said Shiwali Patel, an attorney with the National Women's Law Center who focuses on gender and sexual harassment in schools.

Child sexual abuse is underreported and comprehensive data on educator abuse is lacking. Best estimates show one in 10 kids experience some form of sexual misconduct at the hands of an educator during their K-12 education, according to a 2004 analysis by the U.S. Department of Education.

Four years after the original complaint against Villareal, more students came forward, saying he sexually abused them, too.

The 48-year-old was convicted in April on four counts of felony child sexual assault and was sentenced in July to 50 years in prison.

In court, Villareal maintained his innocence and said there's a conspiracy against him. He intends to appeal the conviction, court records show. He declined to be interviewed by the Press-Gazette.

While it would take years for the full nature of Villareal’s behavior to be known, the girl who originally came forward told the Press-Gazette he touched his second-graders so often, they thought it was “normal.”

"It was so common," she said. "It was like nothing."

Years of concerning behavior

Villareal started teaching second grade at Baird Elementary in 2014. The school is on Green Bay’s east side not far from Interstate 43, and with 539 students, it’s one of the district’s largest elementary schools.

Baird is also one of the district’s five Spanish bilingual schools and has a student population that’s over 40% Hispanic. Villareal was the second-grade bilingual teacher.

For Villareal, it was important that his 7-year-old students liked him, he later testified in court.

His approach to teaching was less structured than the practices of others, one of his former colleagues testified. Villareal agreed.

This meant giving his students prizes and Jolly Rancher candies, which the kids called “jollies.”

Every year, he would offer them the incentive of $1 million to find him a Christian, beautiful, never-married woman, Villareal testified. He suggested maybe one of their moms, maybe an aunt, students told investigators.

Villareal would also make comments about sleeping with women and then ask his students not to tell anyone, according to the criminal complaint.

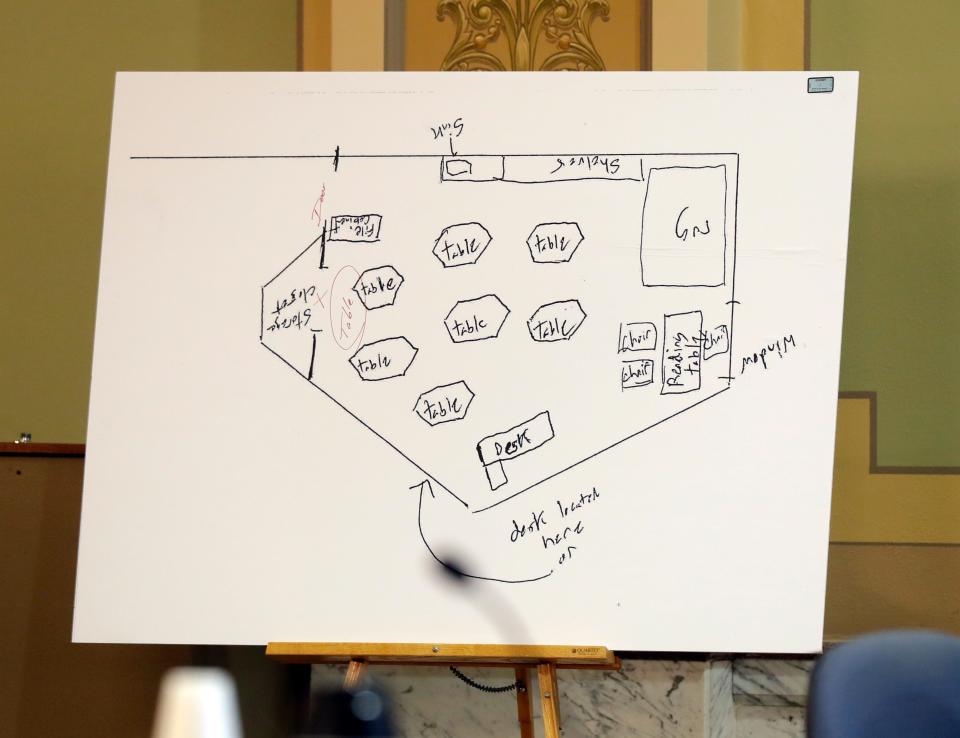

He didn’t make students raise their hands, and they would come up behind his L-shaped desk if they had questions.

A few favorites would eat lunch in the classroom, instead of with their peers. These lunch “dates,” as Villareal described them in testimony, were always with three to four female students, and they happened daily.

He’d share his lunch with the girls — feeding them with his own spoon, one of his students later told investigators.

Then there were the challenges: Who could pull out the largest chunk of their hair? Who would drink some hand sanitizer? Who could hold their breath the longest?

He would ask the girls to do these challenges during lunch, two students later told investigators. The winner would get a prize.

Villareal didn’t hide these lunches. Some of his colleagues knew he ate lunch alone with a small group of female students most days, according to police records and trial testimony.

He’d been doing the lunches even before he got to the Green Bay School District.

From 2000 to 2006, he held them with his kindergarten students when he taught in the Madison Metropolitan School District, according to his testimony and police records.

The Madison district has no record of any sexual misconduct complaints against Villareal, but district policy only requires complaint records to be kept for five years. Because the district doesn’t track what records it destroys, it isn’t known whether any complaints were filed against Villareal while he taught there.

Villareal’s behavior toward his students was a textbook case of grooming, which is when someone progressively tests a child’s boundaries with the ultimate goal of sexual abuse, according to Ian Henderson, the policy director for the Wisconsin Coalition Against Sexual Assault.

“It may be isolating the child. It may be showing special favors to a child, all designed to make the child feel special,” he said. Part of that is encouraging secrecy.

For years, no one seemed to take serious issue with Villareal’s behavior or teaching style — not his colleagues, not his principal and not the school district.

Then, one of his 7-year-old students told her mother that Villareal touched her.

The first allegation

On Jan. 3, 2017 — the second day back from winter break — the mother met with Baird principal Michael Sheean at the school. (The Press-Gazette doesn’t name child sexual abuse survivors or their parents without their consent to protect their privacy.)

Sheean, who was in his third year as Baird's principal, had over a decade of school administration experience.

The daughter had told her mother Villareal touched her "private parts," according to Sheean’s notes of the meeting, copies of which were obtained by the Press-Gazette through an open records request.

A translator also attended because the mother mostly spoke Spanish.

The mother told the principal something else: Her daughter said Villareal touched other girls the same way, according to Sheean's notes.

The girl is now 14, and while she doesn’t remember much about her short time at Baird, she does remember Villareal touching her buttocks.

“From what I remember, I had a paper in my hand, and I was walking over towards him,” she told the Press-Gazette. “I was going to give it to him. I remember turning around, and he touched my butt.”

The touching made her feel embarrassed and humiliated, she said.

In the same interview, conducted with the help of a Spanish translator, the girl’s mother told the Press-Gazette that Sheean defended Villareal during their meeting.

“What I was told by the principal — when the incident happened — is that the teacher was very friendly, he loved the children a lot, and that he was adored by the children because he was a Christian,” she said.

The mother gave a similar statement to police in 2021 where she recalled the school saying it wasn’t like Villareal to do that because he's Christian.

The principal also said Villareal likely meant to pat the girl on her back and accidentally touched her buttocks, the mother told the Press-Gazette.

Sheean did not respond to the Press-Gazette’s multiple requests for an interview.

According to his meeting notes, Sheean asked if he could speak with her daughter, but the mother didn't want him to do it without her. The two agreed to meet with the girl the following day.

After school, Sheean spoke with Villareal and asked him if he remembered any situation like this.

Villareal said he didn’t remember anything like that but had to “stop the girl’s head from hitting a drawer being opened on the filing cabinet,” according to Sheean’s notes.

A tense meeting

At 8 a.m. the following day, the mother and the daughter sat down with Sheean, a translator and Villareal.

In a room full of adults — including Villareal — the principal asked the 7-year-old girl to tell them about the touching.

Experts said talking with a child in front of the alleged abuser should never happen.

Having the alleged abuser in the room compromises the integrity of the investigation, said Child Advocacy Centers of Wisconsin’s Elizabeth Champion, who conducts trainings on investigating child abuse. She said she couldn’t speak about case specifics but talked with the Press-Gazette about best practices.

“What are the odds that (a child is) going to say what they want to say?” she said.

Adele Kimmel said interviewing a victim with the accused teacher present is “terrible.” She’s an attorney with Washington-based legal advocacy organization Public Justice who focuses on gender-based harassment in schools.

“I have not — at least in the last decade — generally heard about schools interviewing the victim with the accused teacher in the room,” she said.

That also went against the U.S. Department of Education’s guidance on investigating sexual abuse complaints at the time.

In an interview with the Press-Gazette, the girl recalled being uncomfortable talking about what happened with Villareal there.

“I felt like he was trying to intimidate me by the looks he gave me, and I felt kind of scared,” she said.

Sheean knew the girl was scared, too.

He wrote in his meeting notes that the girl was “reluctant to say what happened in front of all of us.”

The girl whispered to the translator that “the teacher touched her after helping her with math,” Sheean wrote.

Because she “seemed reluctant to talk,” Sheean had the girl go into a separate office with just the translator.

The translator came back and demonstrated being touched “on the side of the buttocks with an open hand,” Sheean wrote.

The meeting was tense, the mother recalled.

“All the time (Villareal) was looking at my daughter, like trying to say, ‘Don’t talk.’ That’s what I saw in his look,” she told the Press-Gazette. “And the principal looking at me like I was a crazy (person) that went there to create a problem just because.”

Sheean didn't write about any perceived tension in his meeting notes. Instead, his notes stress that the mother said she didn't think there was any intent behind the alleged touching and “doesn’t think anyone should be in trouble.”

However, the mother also told him she might pull her daughter from the school if the girl was too scared to attend, Sheean wrote.

Villareal then deflected the conversation from the alleged touching to academic issues that might have been causing “unhappiness in the classroom,” Sheean’s notes show.

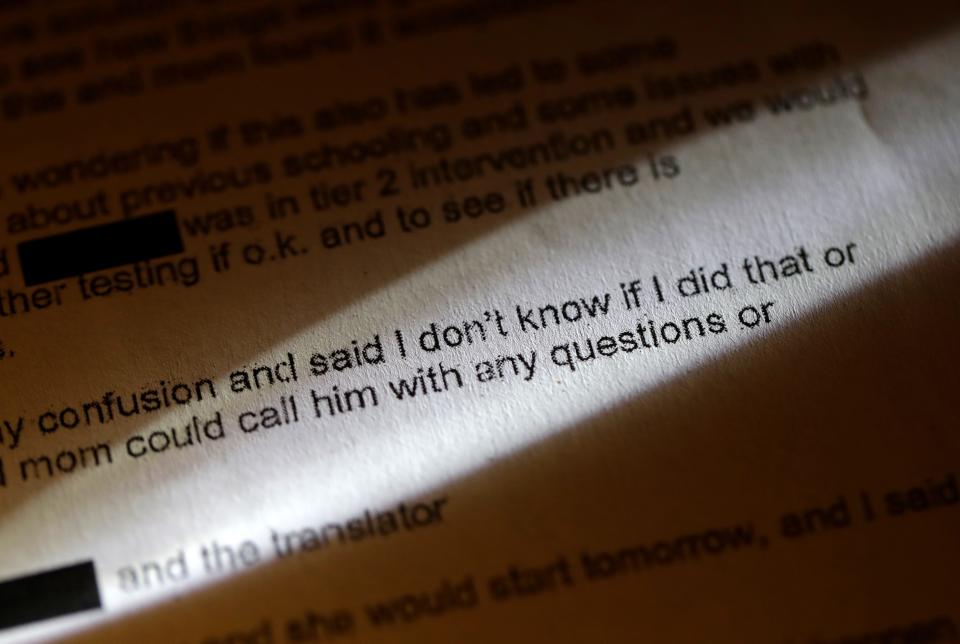

But he didn’t outright deny touching the girl. Instead, Villareal said: “I don’t know if I did that or not. If I did, it wasn’t with any intention.”

Sheean agreed with Villareal’s assessment.

“I told the mom I agreed that there was no intention, but we have to make sure this does not happen and won’t happen again,” he wrote.

A botched investigation

After the meeting, the mother took her daughter home and began making plans to transfer her to a new school the following day.

Randall Etten, the district’s human resources director, interviewed Villareal after school and didn’t require a follow-up, according to Sheean’s notes. Etten did not respond to multiple requests for an interview.

As required by law, Sheean also made a report to Brown County Child Protection Services, according to his meeting notes and emails between Sheean and Etten.

A week later, Sheean emailed Etten and the associate director of pupil services, saying he got a letter from child protection services.

Sheean said his report didn’t warrant “family intervention and no further action was taken” by the agency, according to emails obtained by the Press-Gazette through an open records request.

Child protection services has no legal authority to remove a teacher from the classroom or make determinations about whether a crime occurred, according to Lauren Krukowski, the coordinator of Brown County Child Protection Services. She couldn’t speak about case specifics but told the Press-Gazette about how these cases are typically investigated.

The agency’s role is to offer support services to families and collaborate with police, Krukowski said.

Yet police records show Brown County Child Protection Services never notified law enforcement, as required by agency standards. All reports of sexual contact with children 15 years or younger must be referred to law enforcement.

Had child protection services reported the complaint to police, they would have conducted a separate investigation into the allegation.

In response to the Press-Gazette's questions, Green Bay School District officials repeatedly emphasized that Brown County Child Protection Services came to the same conclusion as the school.

“What is most important is that when the parent brought forth concerns, they were immediately investigated and that the district's determination was the same as another agency (child protection services),” Blakeslee said in an email.

But Title IX investigations are separate and distinct from child protection or police investigations, Title IX attorneys pointed out. Even if another investigation is conducted, schools still must investigate under the federal law.

Because child protection services records are not public, it’s unclear how thorough the agency's investigation was or whether it conducted one at all. The nature of Sheean’s report to the agency is also unknown.

While police records indicate that a Brown County Child Protection Services worker met with the mother on Jan. 4, 2017, she told the Press-Gazette she didn't recall ever meeting with the agency.

The same day Sheean got the letter from child protection services, the Green Bay School District determined through its own investigation that the facts were “inconclusive,” according to emails between Sheean and Etten.

District records show district officials labeled the complaint as “not Title IX.”

Blakeslee, the district spokesperson, said attorneys who believe the district should have pursued a Title IX investigation were likely using new federal regulations and guidelines. But all four attorneys who spoke with the Press-Gazette analyzed the district's response under the laws in place at the time.

Maha Ibrahim, an attorney with Equal Rights Advocates, a California-based legal organization that focuses on gender discrimination, said the district was not exempt from investigating the complaint under Title IX because the mother didn’t want anyone to get in trouble.

“In what universe are you exempted from following the law because a mother told you something?” Ibrahim said.

Kids also don’t have to say the words “sexual assault” for Title IX to apply, Kimmel said.

“If they are talking about touching them on their chest or on their private parts, like they're saying something like that, you have to investigate this as a Title IX complaint,” she said.

The girl and her mother also should have been interviewed separately from Villareal to give their own witness statements about what happened, Kimmel said, calling it “a huge mistake” that the school didn’t do that.

The girl told the Press-Gazette the only time she was interviewed was in the meeting with Villareal.

Since the mother told Sheean her daughter wasn’t the only child Villareal was allegedly touching, the school should have interviewed other students, Kimmel said. U.S. Department of Education federal guidance from the time also emphasized that for similar cases.

School case records do not show the district spoke with any other students in Villareal’s class.

The district also did not notify the mother of its determination, she told the Press-Gazette. At the time, Title IX required that both parties receive written notification of the investigation's outcome.

“I didn’t even know they had done an investigation,” she told the Press-Gazette.

Other gaps in the system

The day after the meeting with Villareal, the girl transferred to a different school, and nothing else happened with the case, the mother said.

The district also didn’t file a report with the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, the state agency overseeing the licenses of teachers and other educators. It conducts its own, separate investigations into reports of educator sexual misconduct.

But state law doesn’t require districts to report sexual misconduct or abuse to the licensing agency unless the educator is arrested, fired or resigns because of that conduct.

Otherwise, it’s discretionary for a school district to report it and for the agency to investigate.

Since Villareal continued teaching, this loophole meant the Green Bay School District was not legally required to report the 2017 complaint to the agency.

The agency supports changing the law and requiring all misconduct be reported to better protect students, according to spokesperson Chris Bucher. In June, Wisconsin legislators introduced a bill that would require all educator sexual misconduct that's reported to child protection services or police be shared with the Department of Public Instruction.

After the district's investigation was closed, Villareal continued teaching for a year with no other official complaints.

Then in August 2018, he arrived at a school training an hour and 40 minutes late, under the influence of alcohol, according to school records.

Placed on administrative leave for a few weeks, Villareal returned to the classroom in mid-September 2018.

Villareal continued teaching until March 2021, when another student came forward saying he sexually abused her.

More girls come forward

On March 26, 2021, at the Willow Tree Cornerstone Child Advocacy Center in Green Bay, a 13-year-old girl sat in a beige interview room.

Across from her was a Willow Tree forensic interviewer — someone who collaborates with police and specializes in interviewing child sexual abuse victims.

In a separate observation room, Scott Asplund, the lead Green Bay police officer on the case, watched the interview on a video feed.

The girl said that Villareal squeezed, slapped and pinched her buttocks every day while she was in his class from 2015 to 2016, according to Asplund’s summary of the interview in the criminal complaint.

The girl talked about “Mr. V’s” lunches, the candy and the toys. One time, Villareal asked who would drink some hand sanitizer, and the girl did, she said.

From the beginning of the school year, she said Villareal would touch her buttocks as she walked away from his desk — similar to what the child who came forward in 2017 said. It happened behind the L-shaped desk, which was pushed up against the wall and had enough height so students couldn’t see behind it.

She also knew of another girl — different from the first child who came forward — with similar experiences.

A few hours after the interview, the Green Bay School District placed Villareal on administrative leave.

Three days later, the district told Asplund about the original abuse complaint against Villareal, the one brought to the district’s attention in 2017.

Asplund and a child protection services worker interviewed the original girl over video call four years after she came forward, according to the criminal complaint and Asplund’s case report of the interview.

The girl told them about Villareal touching her buttocks and having to confront him in the meeting with Sheean. The mother told Asplund she pulled her daughter out of Baird because of that meeting, according to a police report of the interview.

Asplund apologized to the girl’s mother for how the investigation was handled, including the fact that police were not originally involved, according to his case report.

The next day, a third victim spoke with a forensic interviewer at Willow Tree. She was also 13.

The girl was in Villareal’s second-grade class during the 2015-16 school year, the same time as the second victim. She told investigators about the lunches, the requests for a girlfriend, the challenges and the prizes.

She also told them about the touching. When she went to Villareal’s desk to ask a question, he rubbed her vaginal area with his hand.

About a week later, Green Bay Police arrested Villareal at a Sheboygan Kwik Trip off I-43 during his commute to work. He was charged with three counts of child sexual assault.

Two more allegations and years of waiting

Five days after Villareal’s arrest, a fourth victim came forward, saying that he touched her buttocks while she was in the school running club.

Villareal volunteered with the club and was often the group’s “caboose,” the last chaperone making sure kids didn’t fall behind. The girl, who was about 8 at the time, ran in the club from 2015 to 2016.

Villareal would grab her buttocks, pushing her to go faster, the 13-year-old told investigators.

On April 23, 2021, another former student told a school social worker that Villareal had touched her.

The fifth girl — who was also 13 when she came forward — was a second-grader in Villareal’s class during the 2015-16 school year.

On a cold, winter day, she stayed inside with Villareal instead of going out to recess. She didn’t have her snow pants or boots, she later testified.

She was the only one in the classroom with him, and when the girl went to get pretzels from the classroom closet, Villareal followed her.

He cornered her in the closet and rubbed his erect penis against her chest, according to the criminal complaint.

She tried to leave, but Villareal pushed her back against the wall. The girl eventually got away and went outside to recess.

Five days after the fifth girl came forward, Villareal resigned from the Green Bay School District.

In February 2022, prosecutors filed two more child sexual assault charges against Villareal, related to the two girls who came forward after his arrest.

He sat in Brown County Jail on $65,000 bail as he cycled through five attorneys.

After two years of waiting, Villareal went to trial in April.

Villareal’s former students testify to his abuse

One at a time, the girls walked into the largest courtroom at the Brown County Courthouse and took the stand.

The girl who came forward in 2017 didn’t testify. She now lives out of the country, and the mother couldn’t afford to put their lives on hold, travel to Wisconsin and testify for the case, she said.

Because she couldn’t come, that charge was dropped.

The four other girls, now 15 years old, told their stories in front of 14 jurors, a judge and Villareal. All but one is Latina, and they all experienced the abuse during the 2015-16 school year.

The second girl who came forward broke down in tears on the stand, hyperventilating and unable to speak. In seventh grade, she told a family friend about the abuse because she was having nightmares about Villareal.

The friend “told me that wasn’t OK, that that shouldn’t have happened, and it kind of opened my eyes and made me look at it differently,” she testified. That’s when she told her parents.

The third girl to come forward cried as she walked through the courtroom doors, taking deep breaths. When she testified, at times she was no louder than a whisper.

The girl who said Villareal touched her at running club, the fourth to disclose, fidgeted on the stand. She told the jury how Villareal would call her “darling” and touch her buttocks every day at the club.

The fifth victim, the last one to come forward, struggled to get her words out.

In a quiet voice, she described how Villareal trapped her in the closet and testified how she had flashbacks and nightmares.

After their testimony, she and the second girl to come forward embraced each other outside the courtroom, crying.

Brown County Deputy District Attorney Wendy Lemkuil, who prosecuted the case, called 18 witnesses over two days, including students, police officers and Villareal’s former colleagues.

The defense called only one: Villareal.

Villareal takes the stand

In a dark suit with his hair slicked back, Villareal testified for almost two hours.

He confirmed most of what the other 18 witnesses said.

He didn’t enforce classroom expectations and didn’t care if students blurted out questions, he said. Villareal said he kept snacks and Jolly Ranchers in his bottom desk drawer and the classroom closet.

"It was an exception that we would not have lunch in my classroom,” he said.

The lights were usually off, so the girls could see scenes from “Nacho Libre” and other video clips, he told the jury.

“I assumed that teachers knew that I had lunch, lunch dates with my students,” Villareal said.

He clarified that he’d ask his students to help him find a spouse, not a girlfriend.

“I didn’t have issues with that, with finding a girlfriend,” he said. “I told them I would pay some, million dollars if they’d show me an individual that was, first of all, believed in God, they were beautiful and that was never married.”

The prosecutor asked if he ever touched the girls inappropriately. Without hesitation, Villareal denied it.

“I believe that there's quite a bit of conspiracy against me," he said.

On the third and final day, 16 of Villareal’s supporters, including his family, filed into the courtroom for closing arguments.

The jury deliberated for about an hour, and it had its decision: Villareal was found guilty of sexually assaulting four second-grade students at Baird Elementary School between 2015 and 2016. Both his family and the victims were in tears.

In handcuffs, Villareal walked out of the packed courtroom with no visible reaction.

At his sentencing in July, only one victim was there: The girl who Villareal sexually abused at the running club.

When the girl was in second grade at Baird, she had angry outbursts and was suicidal, the mother told the court.

It wasn't until years later, when the mother learned of the abuse, that she connected the dots.

"I will never be able to get the words and images out of my mind of my little girl screaming and crying for help. She almost tried to jump out of our front window to kill herself," the mother said.

"My daughter had been permanently impacted by the actions of someone she was supposed to trust. We will never know what (she) was going to be and the type of person she would be in her future because David took that from her. He stole her innocence," she added.

Villareal continues to not take responsibility for his crimes, according to a presentence investigation report referenced in court. He didn't speak at the sentencing.

Brown County Circuit Court Judge Donald Zuidmulder, who presided over the case, sentenced Villareal to 50 years in prison ―18 years longer than what the state recommended. It's effectively a life sentence, given his age.

“How is it not absolutely the fact that every parent in this town, in this state and in this nation should be confident, when they send their children to a public school, that that’s a safe place?" Zuidmulder said at the sentencing.

The girls were entitled to positive life experiences and a normal journey, he said.

“Four little lives have been altered forever."

The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction revoked Villareal's teaching license in May, as required by state law.

The Green Bay School District has made no changes to the way it handles Title IX complaints because of the Villareal case, according to Blakeslee. The district maintains it followed Title IX requirements correctly.

The girl who originally came forward didn't get her day in court. It's been six years, and her mother remains frustrated that school officials, especially Sheean, have not acknowledged mismanaging her daughter’s case.

“It makes me mad that everything is based on David Villareal,” she said. “Because (Sheean) had knowledge and ignored the situation.”

"It bothered me," she said. "And still does."

Danielle DuClos is a Report for America corps member who covers K-12 education for the Green Bay Press-Gazette. Contact her at dduclos@gannett.com. Follow her on Twitter @danielle_duclos. You can directly support her work with a tax-deductible donation at GreenBayPressGazette.com/RFA or by check made out to The GroundTruth Project with subject line Report for America Green Bay Press Gazette Campaign. Address: The GroundTruth Project, Lockbox Services, 9450 SW Gemini Drive, PMB 46837, Beaverton, Oregon 97008-7105.

Green Bay Press-Gazette reporter Ariel Perez contributed to this report.

How we reported this story:

This story is the result of eight months of reporting.

The Green Bay Press-Gazette obtained records from the Green Bay School District, Green Bay Police Department and Brown County Circuit Court, which included hundreds of pages of the victims’ accounts, case documentation and school district emails.

The reporter attended the entirety of Villareal’s jury trial in April, listening to over seven hours of testimony from the victims, parents, students, police, teachers, and Villareal himself.

Most of the details about Villareal’s behavior toward his students and the nature of the abuse come from witness accounts in public records and trial testimony.

The reporter reviewed more than 100 pages of federal Title IX requirements and guidance that were in place when the first complaint was made against Villareal in 2017. Much of that federal guidance has since been rescinded due to changes in federal regulations.

We also interviewed four Title IX attorneys and two experts who work with child sexual assault survivors in Wisconsin.

We didn’t name the survivors or their parents to protect their privacy.

In May 2023, the Press-Gazette interviewed the mother and the child who made the original complaint against Villareal in January 2017 about how the Green Bay School District handled the complaint. Key points in their story were corroborated in police, court, and school district records — along with trial testimony.

Reporters tried to contact all the victims’ families for interviews, but only the mother and daughter who originally complained responded to our requests.

Where to get help:

If you or a someone you know is a survivor of sexual abuse, here is where you can get help.

For children:

Contact your local Child Protective Services agency to make a report and receive supportive services. The Wisconsin Department of Children and Families has an interactive map listing local agencies in Wisconsin: dcf.wisconsin.gov/reportabuse

If it’s an emergency, contact your local law enforcement by calling 911.

If your child discloses something and they’re not in immediate danger, call your local police non-emergency number to make a report to law enforcement.

For adults:

The Wisconsin Coalition Against Sexual Assault lists crisis centers and support services across the state. Find service providers in your area at www.wcasa.org/survivors/service-providers/

The 24/7 confidential National Sexual Assault Hotline is available at 800-656-HOPE (4673).

The Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN) has crisis support services such as online chat hotlines for survivors at www.rainn.org/resources

RALIANCE has a directory of rape crisis center’s in each state: www.raliance.org/rape-crisis-centers/

This article originally appeared on Green Bay Press-Gazette: David Villareal investigation botched by Green Bay school district