Solar sizzle or environmental fizzle? The Muddy Creek agrivoltaic conundrum

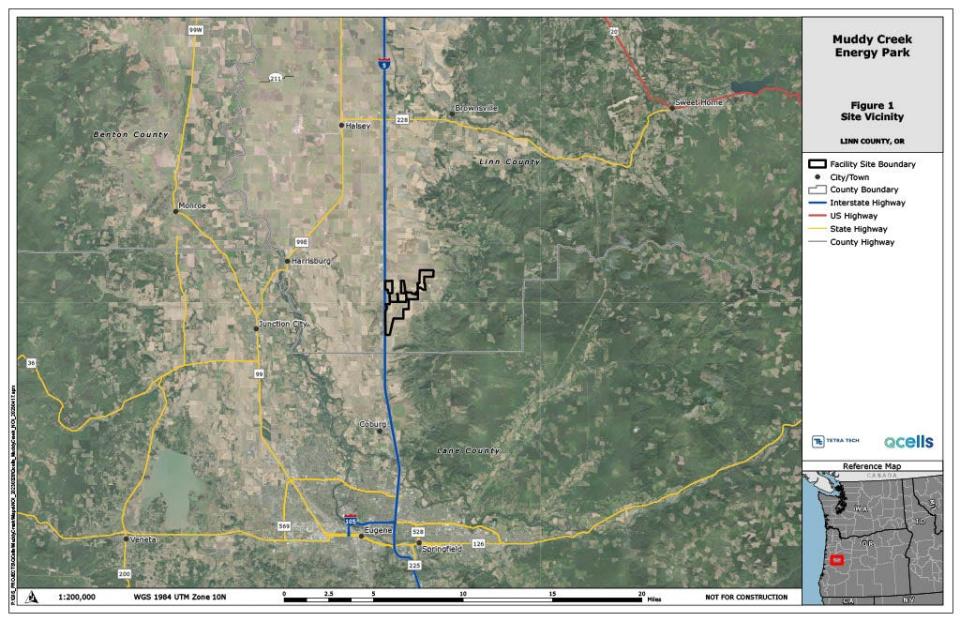

The checkered green hills south of Brownsville are bursting with life in the spring, home to seasonal wetlands and migratory birds, a picturesque scene motorists take in as they make their way up Interstate 5 between Eugene and Salem.

Those hills could be changing, though, taking on an entirely different shade of "green," if plans go forward for a proposed 2.5-square-mile agrivoltaic solar energy park.

The Muddy Creek Energy Park, under consideration in Linn County, has drawn backers and detractors alike as it's made its way into local conversation.

For many, it has raised questions about what the project might look like and how it might affect the surrounding environment. In March, dozens of stakeholders gathered at an area high school to learn more about the project from the Friends of Gap Road, a volunteer advocacy group campaigning to stop the project.

At the same time, supporters say the Muddy Creek facility could offer an enticing way to produce renewable energy without sacrificing the type of agriculture historically associated with the Willamette Valley.

The project is being proposed by QCells USA, a subsidiary of solar energy company Hanwha QCells USA Corp., based in South Korea with engineering headquartered in Germany.

The proposed energy park site boundary would occupy approximately 1,588 acres of private, cultivated, high-value Exclusive Farm Use zoned land, according to the Oregon Department of Energy. The Project Order Notice of Intent states the facility would generate approximately 199 megawatts of energy expected to be able to power 34,000 homes.

The Project Order notes the energy park may be subject to the issuance of at least 21 necessary permits obtained through 11 different authorities ranging from the federal, state and county levels. In order to move forward with project planning, a two-year wildlife study will need to be conducted.

What is agrivoltaics?

The term agrivoltaics combines the facets of agriculture, or food production, and voltaics, or energy production.

This combination of food and energy production addresses an essential intersection of life as we know it between food, water and energy resources. This intersection is so fundamental that in 2021, Oregon State University established the North Willamette Research and Extension Center in Aurora to model sustainable farming systems. The five-acre research farm has put agrivoltaics under a microscope, to test how converting farmland to agrivoltaic lands could benefit communities across the globe.

OSU Associate Professor Chad Higgins has been conducting topic research and supporting this program for years. He explained the central idea of agrivoltaics as the effort to co-locate agriculture and photovoltaic energy generation on the same parcel of land in a way that mutually benefits and acts as an asset for both ventures.

Plants can’t use all the light they receive on a sunny day, which is where co-locating solar panels comes in. With excess sunlight, plants begin to overheat, leading to wilting or crispy leaves. Plants will release water much like humans will sweat to regulate temperature. Shade benefits plants by reducing the amount of time they experience stress from prolonged heat or light. In reducing that stress, Higgins said plants need less water. If roughly 30% of crops are shaded, those plants will use about 30% less water, according to his research.

If you have ever gone from a space with asphalt to an area with lots of greenery on a hot day, you’ve felt the cooling effects of plants. Much like how a phone will overheat in a hot car, solar panels can overheat and lose productivity. Having plants co-located with solar panels can help keep them at an optimum operable temperature for peak performance by producing a “micro-climate that is more conducive to solar,” according to Higgins.

For Higgins, it’s vital that agrivoltaic energy parks implement what he calls “ag-first design,” where adapting design to the practices of the land managers and farmers for that parcel is prioritized. His “farmers-first” perspective centers on agricultural needs.

Designs that focus on the agricultural production of land come in two formats: steel posts holding solar panels can be raised to allow for farm equipment to pass underneath them, or panels can be placed on hinges that give them the ability to tilt out of the way of machinery that moves past. Hinging solar panels is the model utilized at OSU’s research farm.

“A solar project has to be of the community, not above the community. It has to be part of the community in which it exists and if that’s a farming community, that community is going to want to see farmland preserved and maintain the farming legacy of that site,” Higgins said.

“Discussing the qualities of land that is attractive to solar, that basically describes ag land so a lot of large-scale solar development is aimed at places and communities that have had a traditionally ag focus.”

Higgins said land suitable for solar development is often flat, gets lots of sun, is near to infrastructure and has already disturbed, deep soils.

“That has a lot of overlap with agricultural lands in terms of a description,” Higgins said.

“There are very few spots that have that ‘Goldilocks’ combination of things.”

Agrivoltaics are being woven into design planning for solar parks and Higgins said this co-location stems from the often shared concerns of residents near solar projects that they want to see the agricultural heritage of that land preserved. He said this philosophy of preservation is reflected in Oregon’s land use laws with Exclusive Farm Use zoning.

“Agrivoltaic practices have been adopted extensively in solar production and solar development now as part of the practice of developing solar projects. I think that’s market forces pushing them in this direction because a solar project has to be of the community, not above the community. It has to be part of the community in which it exists,” Higgins said.

“If that’s a farming community, that community is going to want to see farmland preserved and maintain the farming legacy of that site.”

As for whether or not agrivoltaic projects are still considered farming if solar panels are present, Higgins said this is a philosophical question. He argues that yes, it is still farming because solar panels optimally manage a farming resource — light — and sees solar panels as another piece of farming equipment.

“I come at this from a farmers-first perspective. It seems a shame and a lack of imagination to me to not farm land under solar panels when you can easily design systems that make them almost fully accessible to ag equipment and still farm them,” Higgins said.

“I think companies have woken up to the fact that it’s a much easier path toward engaging with the community if you’re not completely disrupting the community in terms of what that land use would be.”

Friends of Gap Road and community concerns

Public comments provided to the Oregon Energy Facility Siting Council throughout the summer of 2023 cited numerous concerns with the development. The Project Order cited the issues most discussed in public comments as: conversion and preservation of high-value farmland, possible habitat and wildlife impacts, potential soil and hydrological impacts, impacts to health and safety and concerns about solar facilities materials, waste and lifespan.

Dave Rogers is a founding member of Friends of Gap Road. He has lived south of Brownsville for about 45 years and owns a business, River Refuge Seed, and a 750-acre farm. River Refuge Seed has been in business since the mid-80s, growing specialty restoration crop seeds and selling them nationwide to individuals, businesses and government entities restoring wetlands.

Rogers said his whole family, including his son and five grandchildren who work at River Refuge Seed, all have a deep love for waterfowl, wildlife and wetlands. He said he is primarily concerned about the seasonal wetlands the project is proposed to occupy.

“I love what I do. I create wetlands not just for me but for other people, neighbors and friends as well as a business,” Rogers said. “Our River Refuge philosophy is that we are a wetland.”

Rogers formed Friend of Gap Road alongside Troy Jones, Arnie Kampfer and Stephanie Glaser Hagerty about six months ago when community members were made aware of the proposed project. About a month after forming, the group had amassed nearly 100 supporters. Now, Rogers estimates the number of supporters backing Friends of Gap Road is pushing 200.

He said it has been easy to stay involved in opposing this energy park because of his relationship to the land already coupled with the support of other members of Friend of Gap Road. Many folks voice the same concerns for preserving existing wetlands and maintaining the land for Exclusive Farm Use.

“I am really passionate about this, I work on wetlands all the time so it's really close to my heart,” Rogers said.

“It was really gratifying to see how close it was to the majority of these people that have joined us.”

Rogers said the optimal outcome from the work Friends of Gap Road is doing would be to see the project moved elsewhere, ideally to the eastern side of the state where the climate is drier, there are more days of sunshine and the land is more suitable for grazing livestock. He said the biggest concern Friends of Gap Road has is that if approved, this project could set a precedent for the introduction of other large-scale photovoltaic energy parks to move onto Exclusive Farm Use land across the Willamette Valley.

“Our group absolutely believes this: we are not against solar power, absolutely not,” Rogers said.

“What we’re against is where they’re going to put it.”

Opposition to the project spans across the aisle, coming from both liberals and conservatives, according to Rogers.

“Most of us are pretty conservative but in this particular instance, we’re working hand-in-hand with 1000 Friends of Oregon and 1000 Friends of Linn County,” Rogers said.

“We are working hand-in-hand with environmentalists at the same time so it's great meeting in the middle, too.”

Expert input

Higgins said solar project developments are subject to many surveys before they are built to make sure that wildlife, habitat, cultural and community impacts are considered. Long before any project is allowed to be placed, standards must be met. Even after a project is set for decommissioning, Higgins said the impact on the land from the panels themselves is minimal due to the placement of steel poles hammered into soil being the only part of a solar panel in contact with the ground.

As far as removing solar panels to decommission a project, Higgins said installations need to minimize roads and gravel added to the site to make removal easier and less impactful to the land.

“A good removal starts with a good installation,” Higgins said.

He said uninstalling panels includes unbolting them from the poles they’re on and shipping the solar panels to a recycling facility in Texas, where about 95% of the material is recyclable. The steel poles holding the panels are also sent to a steel recycling facility, where Higgins said nearly 100% of that material can be recycled.

There is a misconception that solar projects could be abandoned, leaving a slew of non-operable equipment to occupy the land that could be otherwise used, Higgins said. He said companies developing these projects are required to put up bonds specifically for decommissioning the panels before efforts to place them can be made. This bond is made to adjust for inflation and ensure that even if a company goes belly-up, there is no bankrupting out of properly decommissioning a solar energy park.

He said concerns about leaching chemicals pertain to batteries storing power. With the Diamond Hill substation located at the edge of the proposed project boundary, power generated from the Muddy Creek Energy Park would theoretically not need batteries for energy storage on-site, although finalized project plans are not currently available.

Higgins said he hears questions about the validity of modeling a roughly 1,600-acre project after OSU’s five-acre research farm, where people wonder whether it would still be effective at a larger scale. He said this concern is “fair enough,” but that economies of scale dictate that if a project works effectively at five acres, then it would be even more profitable per acre at a larger size due to discounts and economies of scale.

“I know that it works because we literally already built it,” Higgins said.

Higgins said the jobs generated for folks farming the land and for solar energy employees help benefit the community the project is in and lease payments from solar companies can help family farms stay solvent.

“I think a lot of people have concerns about ag land being taken out of production because agricultural land is very precious, they’re not making any more of it. We have to be good stewards of the ag land that we have,” Higgins said.

“It just preserves the land as farmland. That’s what it does and I think that’s a good thing.”

What's next?

The Notice of Intent filed by Q Cells is set to expire on May 18, 2025, unless the applicant files a petition with the Energy Facility Siting Division of the Oregon Department of Energy to extend the date. Q Cells did not respond to requests for comment.

While the company conducts wildlife and environmental surveys to assess the land of the proposed project, Rogers said Friends of Gap Road will continue to educate others about their concerns for this project.

“There isn’t anybody that shouldn’t take some interest in this,” Rogers said.

“This project is going to affect everybody in the valley. Right now, it’s just south of Brownsville but in the long run, it's going to affect everybody and there is nobody who wouldn't be at least a little bit concerned about it.”

Hannarose McGuinness is The Register-Guard’s growth and development reporter. Contact her at 541-844-9859 or hmcguinness@registerguard.com

This article originally appeared on Register-Guard: 'Muddy Creek' solar agrivoltaic plan near Brownsville sparks debate