'Tecumseh's Eclipse' in 1806 event brought fear, threat of attack

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Tecumseh's Eclipse of 1806 was the last time the sky over Stark County − or anywhere in Ohio − went as dark as night during the day.

"On June 16, 1806 a total eclipse of the sun cast a shadow across much of the northeastern United States," noted a 2016 posting at the website for Middlebury College, which explained the astronomical event was "known as 'Tecumseh’s Eclipse' for the role it played in the Shawnee chief’s efforts to form a tribal confederacy."

On Monday, April 8, 2024, the darkness will come again. According to Ohio.gov, the next total solar eclipse after that in Ohio will be in 2099.

"Portions of Stark County fall within the path of totality for the solar eclipse," notes a posting at VisitCanton.com, which offered scientific information about this year's eclipse, along with advice about how to safely and conveniently view it.

The 2024 eclipse in Ohio will be from 3 to 3:20 p.m., Visit Canton explains. The path of totality will enter the state from the southwest and will progress northeast. Viewing in any given location can be from 30 seconds to more than four minutes, depending upon how close the position is to the center line of the path of totality.

"Find the best viewing locations and special events to experience this marvel of nature," the Visit Canton website adds. "The 2024 event is anticipated to be the most-watched total solar eclipse in history!"

The eclipse of 1806, while occurring too long ago for any of us to personally have experienced, was equally a "marvel of nature." The once-in-a-lifetime event has been hyped even more by claims it also was significant historically.

Or, was a prediction that was made of the eclipse just an interesting story occurring at a time when much history was recorded long after the fact?

"I can’t see that the eclipse of 1806 had any real impact on society – Native or European – in any significant sense with regard to enlightenment or Astronomical understanding in the era," said Thomas J. O'Grady, who has taught observational astronomy at Ohio University almost four decades. "People were more about getting their living. People were busy and media was a small, although important, part of people’s lives. Now it is a major part of people’s lives."

Still, regardless of its veracity or consequence, the eclipse of 1806 has captured the attention of both avid astronomy enthusiasts and infrequent skywatchers as the eclipse of 2024 approaches.

Astronomer to speak

O'Grady will speak on eclipses at 6:30 p.m. March 20 at Columbus Metropolitan Library in Dublin, Ohio. Part of that talk will be about the 1806 eclipse.

As a part-time astronomy assistant who teaches night courses at the Astrophysical Institute at Ohio University – offering "the hows and whys" of celestial mechanics – O'Grady claims not to be an astronomer or an eclipse authority.

"I am not a scientist. I am an observational astronomy Instructor and an astronomy enthusiast," he said. "My day job these days is working at the Southeast Ohio History Center. I am not a trained historian. I am a history enthusiast."

Still, he focuses for a time each class on solar and lunar eclipses. Such eclipses are a subject on which O'Grady can speak with an abundance of experience.

"I went to Columbia, South America, in October 1977 to observe my first total eclipse of the sun. It was a 29-second eclipse on the centerline," he recalled. "A long way to go for a 29-second thrill, even though clouds covered the event at the moment of totality."

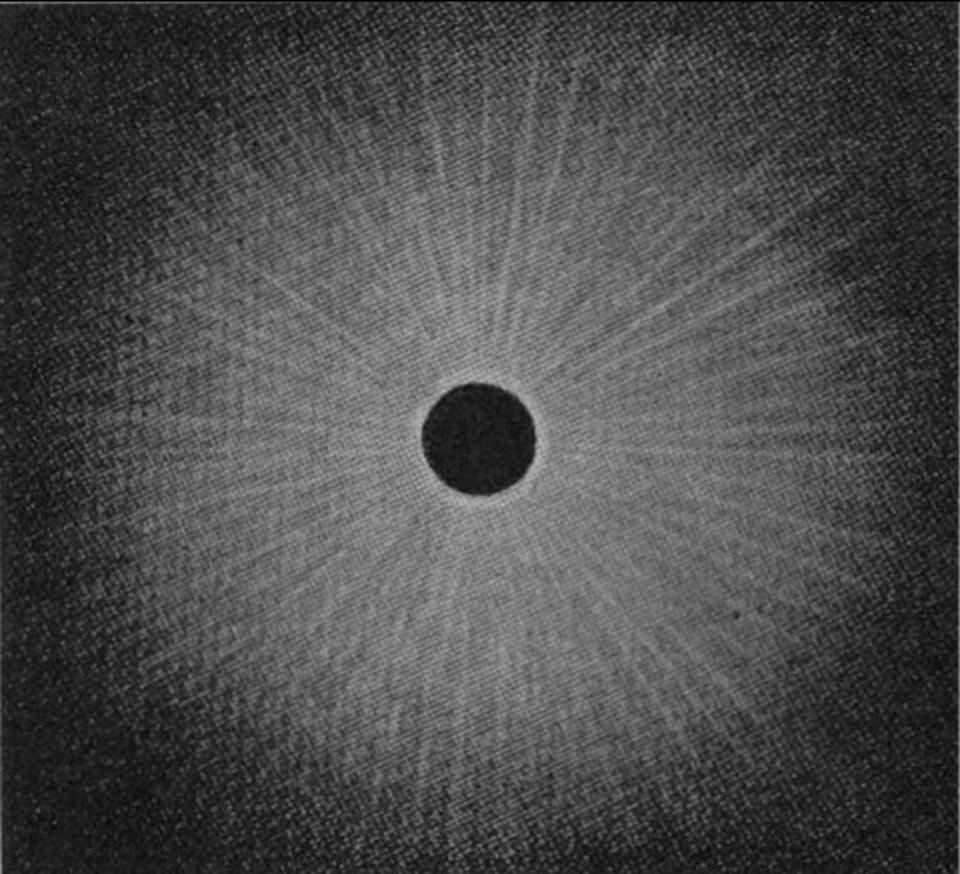

"There was an appearance of a sunset in all directions around us – a 360-degree sunset," he said, recalling the small gathering of people initially hooted and hollered. Then, "it got sublimely silent. I felt goose pimples and the hair seemed to stand up on the back of my neck."

Fueled by that "lasting impression," O'Grady traveled in 1979 to Manitoba, Canada, to see another solar eclipse.

"I have traveled to Assateaque Island in May 1984, Mexico in July 1991, Venezuela in February 1998, Egypt in 2006, and Oregon in 2017," he said. "So, I have made some effort at chasing the moon’s shadow."

Tecumsah sought brother's prediction

An equal passion for researching Ohio history led O'Grady to look into the eclipse of 1806.

"My interest in that eclipse has been on the periphery for a while," he said. "But now there is the solar eclipse of April 2024, which brings the eclipse of 1806 back into perspective. The first total eclipse in the Ohio country since Tecumseh is here. ... This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, and it is coming to Ohio."

History records the eclipse of 1806 provided Tecumseh with an opportunity to foster his quest to unite tribes in east and central North America in their struggle against the migration west of settlers. He enlisted the help of his brother, Tenskwatawa, who also was called The Prophet.

O'Grady said history places Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa at Greenville, Ohio, as weeks led up to the 1806 eclipse. William Henry Harrison, governor of the Indiana territory and later a U.S. president, challenged The Prophet to prove his power.

"If he (Tenskwatawa) is really a prophet," Harrison supposedly wrote, "ask him to cause the Sun to stand still or the Moon to alter its course, the rivers to cease to flow or the dead to rise from their graves."

After consulting with Tecumseh, The Prophet did what Harrison requested. He predicted the eclipse.

"Fifty days from this day there will be no cloud in the sky," is a version of The Prophet's reply. "Yet, when the Sun has reached its highest point, at that moment will the Great Spirit take it into her hand and hide it from us. The darkness of night will thereupon cover us and the stars will shine round about us. The birds will roost and the night creatures will awaken and stir."

How did it happen?

O'Grady notes there are "few details" proven concerning the incident.

"The facts are sketchy in many ways," he said. "It is difficult to ascertain who initiated the story for historic purposes. Not much in the way of interviews ... and newspaper articles or books written by eyewitnesses."

Word of mouth transfer "kept the story alive" before it became a part of the written history of Ohio, he said. "And it doesn’t show up in all histories.”

"Word of mouth transfer is, of course, subject to interpretation and choice of wording each time it is passed on. We’ll probably be as sure of the facts of this story as we are of the location of Tecumseh’s burial place."

Tecumseh and The Prophet likely got the "street cred" they sought, O'Grady said.

"With the eclipse of 1806 I believe it was a bit of a ruse promulgated by Tenskwatawa and Tecumseh after William Henry Harrison had notified other tribal leaders that these brothers were a hoax and if they had any powers they should demonstrate them," he said.

"Some imagine that Tecumseh learned about the upcoming solar eclipse when he was on his journeys trying to put together a confederation of Native tribes," explained O'Grady. "Sharing that info with 'The Prophet' was probably the opportunity for the knowledge to be used or exploited to aid the Native effort. Harrison probably helped the story to take place. It probably wouldn’t have happened without his input – inadvertently."

Few today will be afraid

That "darkness of night" during the day was almost 220 years ago. What kind of 'day-night' should people in Stark County − and much of the rest of Ohio − expect to see April? And how will they react to the darkness?

"Viewing a total eclipse of the sun does influence people," said O'Grady. "I would say that most people in 1806 did not see the eclipse. I would say that hardly any people traveled to the path of totality to witness it. ... I would say that nearly everyone along the path saw it get dark and it was clear they saw the corona and any planets that came into view. I would say hardly any knew or understood what was happening and probably many experienced some fear."

Few will be frightened by the darkness this time. Too many scientists, mainstream news outlets and social media networks have spread the word and offered an explanation.

"While some Native Americans and some early settlers were informed of the upcoming eclipse they had no hard data about exactly when and where it might occur (in 1806)," noted O'Grady. "Most just found themselves in the moon’s shadow, unexpectedly – for the most part."

"By April almost no individual in Ohio will be unaware of this (2024) event," observed O'Grady. "This is a world of difference from the last occurrence."

Still, expect an awesome occasion. Well, it might not impress everyone.

"I predict, however, that there will be people in ... locations along the path of totality that will not leave their (electronic device) screens or other distractions and go out of doors for a couple of minutes to observe this. ... That will be a phenomenon almost as amazing to me as the eclipse itself."

Reach Gary at gary.brown.rep@gmail.com. On Twitter: @gbrownREP.

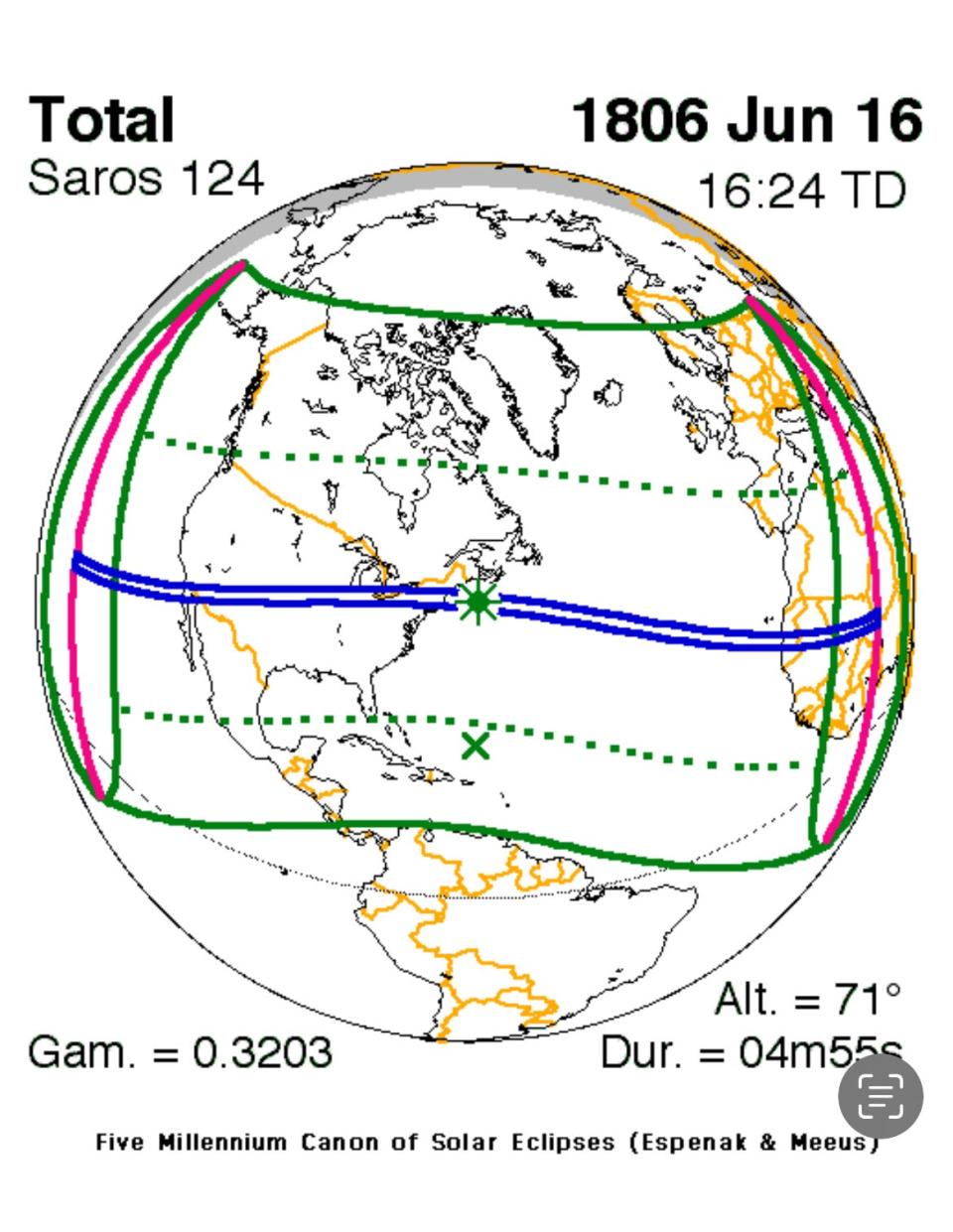

A pair of paths

How does the eclipse of 1806 compare with the upcoming 2024 eclipse?

Thomas J. O'Grady, an observational astronomy instructor for Ohio University, compares their paths.

"The path of totality in 1806 was from a more northerly location in the west and moved almost directly east across the planet from sunrise to sunset. In 2024 the shadow with hit out in the Pacific Ocean at sunrise and travel across Mexico and up through Texan and northeasterly across the U.S. to Ohio and over Cleveland and Buffalo, New York and Niagara Falls and Maine and end up in the north Atlantic at sunset.

"They are two very different paths."

This article originally appeared on The Alliance Review: 'Tecumseh's Eclipse': 1806 event sparked fear, threat of attack