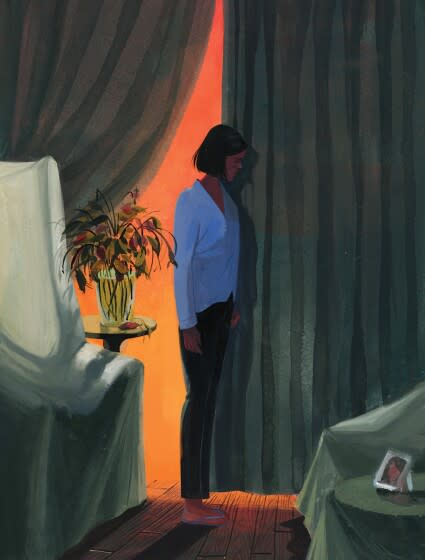

'Ted Lasso,' 'Severance,' 'White Lotus': TV series explore the grief haunting characters

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In “Ted Lasso,” an American football coach, his marriage falling apart, escapes to England, where he hides his grief and anxiety beneath can-do optimism.

In “The White Lotus,” a hopeless neurotic takes her mother’s ashes to a luxury resort in Hawaii, where she can talk about little else besides her sadness.

In “Severance,” a recent widower takes a job with a corporation that surgically splits his work self memories from his home self, fleeing from the grief that haunts him whenever he’s not in the office.

These three Emmy juggernauts — “Ted Lasso” and “The White Lotus” earned 20 nominations each, while “Severance” picked up 14 — are largely driven by grief. After two-plus years that have seen COVID-19 claim more than 6 million lives, death’s aftermath has become a storytelling staple (not that it’s ever been very far away). On the best TV shows, emotionally battered characters go to any length to postpone grief, or sever it, or take it on a vacation, only to find that it won’t be denied. You can only wait it out, and even then, it doesn’t really go away. The rest of one’s life just grows new roots around it.

Take Mark, the grieving office drone played by Emmy nominee Adam Scott in the Apple TV+ drama series “Severance.” He just wants to forget his wife’s death, and for eight hours every day he can do just that. The Lumon Corporation has pioneered a surgical procedure that severs a worker’s “Innie,” or life inside the office, from his or her “Outie,” or life outside. For Mark and his co-workers, this means an opportunity to leave real life, and grief, behind.

Not surprisingly, complications arise.

“Grief, and specifically in Mark's case, the loss of his wife, is very much the driver of the story, on both sides of the severance barrier,” says series creator Dan Erickson. “He doesn’t know it, because he doesn’t know anything he’s doing at work, but it's all part of this massive avoidance of this deep pain that he's feeling. The show overall really is about disassociation and avoidance and sort of cutting ourselves off from the parts of us or the parts of our lives that make us uncomfortable or make us sad.”

It’s an understandable impulse. Talk to a grieving person and you’ll hear of a desire to just stop the hurting, to press pause or fast-forward or bring back the reality that existed before loss erased it. The pain is like nothing else. Some turn to drinking and drugs, numbing agents with obvious consequences. But the grief is always waiting on the other side.

Loss doesn’t always mean death. You can grieve a way of life, or a job, or, as just about anyone can tell you, a relationship. In the Apple TV+ comedy series “Ted Lasso,” Jason Sudeikis, also an Emmy nominee, plays a fish out of water who always seems to have a positive spin on everything — a joke, a pun, a pop culture reference, some bit of sage wisdom. A successful college football coach in the States, Ted has moved to England to coach soccer, a sport he knows nothing about. Leading with his blinding optimism, he’s actually falling apart. We learn he’s moved abroad not just to coach but also to escape the reality of a dying marriage (the marriage isn’t dying because he moved; he moved because the marriage is dying). Eventually, he has a panic attack on the sideline. Anxiety, a frequent companion of grief, has taken its toll.

Erickson can relate. The inspiration for “Severance” came largely from a devastating breakup he endured. “I was having a lot of trouble coming to terms with it,” he says. “At that time, I found a weird level of comfort in being at work and being able to just follow directions and not be able to even really think about my own pain. There was a real solace in that. So I think it's baked into the concept of the series. It's inextricably part of the idea.”

Work is a popular escape strategy: see also “The Bear,” the popular new FX series about a five-star chef (Jeremy Allen White) who throws himself into running his late brother’s Chicago sandwich shop. Or maybe a vacation is in order. In the HBO limited series “The White Lotus,” Tanya, played by Jennifer Coolidge, another Emmy nominee, travels to a Hawaiian resort, where she joins an emotionally stunted group of guests for a week of idle sunshine. She is carrying her mother’s ashes, a fact she is eager to share with anyone who will listen. She plans to scatter Mom at sea, maybe pay respects and lighten her load a little.

But Tanya is, to put it mildly, a mess (if she weren’t, she wouldn’t be part of this show). She’s a hopeless narcissist, and she clings to her grief fiercely, as many do. She meets a guy (Jon Gries), who gives every indication that he too is dying. That means she’ll get to go through the whole ordeal again.

As much a part of life as life itself, grief is included in everyone’s story. It makes sense that television would claim a piece for itself and reflect our pain back to us.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.