Before teen was killed, dead pines were a problem on Idaho 55. What the state knew

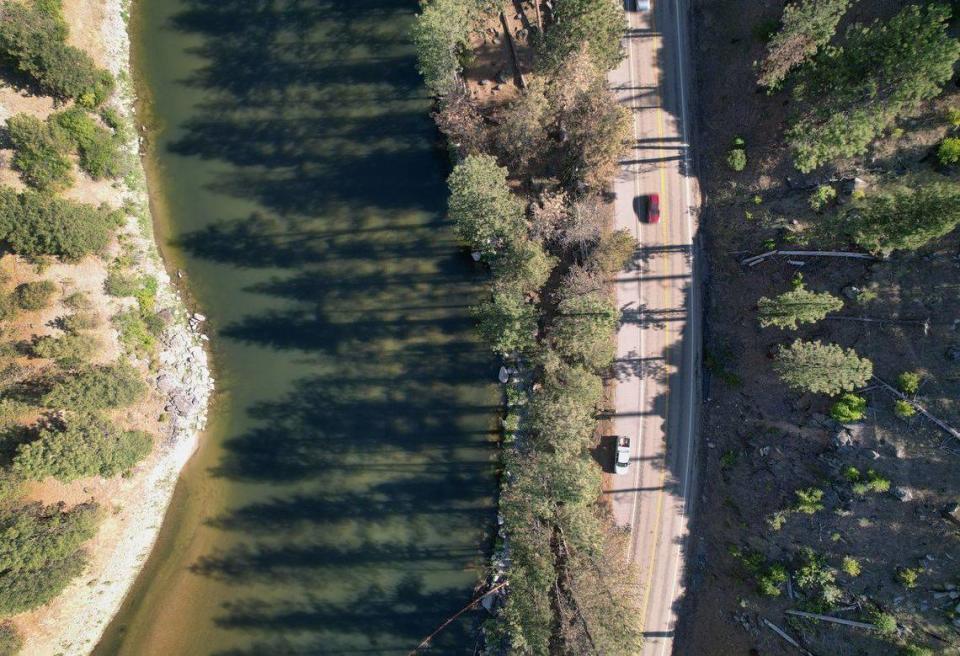

On a good day, Idaho 55, a popular highway connecting Boise to McCall, is a hazardous road. Cars and trucks whip around tight curves with little shoulder. Signs warn of falling rock. A couple of roadside memorials stand along the highway, a reminder of fatalities that occurred.

Ultimately, it was the many tall, dying ponderosa pine trees standing close to the road, especially north of Horseshoe Bend, that caused the death of a teen last month.

At around 5:20 p.m. on June 7, 13-year-old Coltin Jones and his grandmother were traveling during a windy storm on that road when the top of one of those trees snapped off and hit their car. The tree killed Coltin and put his grandmother, Marsha Gallagher, in the hospital with “serious injuries,” according to the Boise County sheriff.

A month after Coltin’s death, the Idaho Transportation Department and the U.S. Forest Service began cutting down about 150 trees near the area where the boy was killed. Forest Service employees cut the trees, while ITD staff removed trees from the road and directed traffic.

But those trees have been on the radar of the Idaho Transportation Department, which has the responsibility to maintain the highway, since at least November 2021.

Members of the public have also raised concerns. Before Coltin’s death, ITD officials planned maintenance projects to cut down what they termed “hazard trees” in internal emails, which were obtained by the Idaho Statesman through a public records request. They did not implement those initiatives before Coltin was killed.

ITD knew of trees’ safety hazards

In November 2021, Cory Kelly, a transportation technician for the Transportation Department, emailed David Dansereau, an ITD fleet business operations manager. “I would like to start working on getting a contractor to come in and remove the dead trees on Hwy 55 from Horseshoe Bend to Donnelly,” he said.

One year later, Eric Copeland, the field operation manager responsible for Idaho 55, echoed Kelly and sent another email to ITD colleagues about the trees in the area where Coltin was killed. “I just got off the phone with the Forest Service and they would like ITD to remove some hazard trees on ID-55 between Milepost 73-79,” he wrote.

“I think I know the trees they are talking about, been dead for a while now,” replied Aaron Bauges, an ITD supervisor.

Copeland responded that Idaho Transportation Department officials wanted to get them cut down in the spring, but that the project was more than their maintenance workers could handle.

“Putting this one together took a while,” Copeland told the Statesman months later. The project was dependent on the Forest Service’s schedule to cut the trees, he said. The department has been discussing it for two years, but it was hard to coordinate the two agencies, he added.

For the past two years, the Idaho Transportation Department has also discussed a larger contract to cut down trees on Idaho 55 that would be separate from the Forest Service work, partly because of concerns about driver safety, Copeland said. It’s taken that long because the state agency has a lengthy contracting process, he said.

The tree that killed Coltin, near mile marker 77, was dead for about two years, said John Wallace, the district ranger for the Emmett district of the Boise National Forest. “It had no needles, the top portion of the tree, the bark was flaking off. It had been there for a while,” he told the Statesman.

The Forest Service manages some of the land along the highway. But if there’s a dead tree next to the highway, it’s ITD’s responsibility to cut it down, Wallace said.

“We’re not necessarily directing them (on) how to do their job,” he told the Statesman.

The department removed some pine trees before Coltin’s death, but on a smaller scale. ITD cut about six trees on the road as of late June. Last year, they removed around the same number of trees, and in 2021, they took down 20 or more, Copeland told the Statesman.

People outside the agency have raised the alarm, too. Randy Fox, a conservation associate at the Idaho Conservation League, said members have contacted the organization and complained that the trees pose a safety risk.

Jon Carter, a retired lawyer who lives in McCall, submitted an editorial to the Statesman in 2021 about dead trees on the highway. “What was once a lovely drive has turned into a drive of death — tree death,” he wrote. “It is not a good look for Idaho.”

And in an email he wrote to Gov. Brad Little in March, he asked the question: “Is the state planning to remove them or leave (them) in place, where they will continue to be an eyesore and hazard for years and years?”

Little’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

Carter said he’d also made calls to the Idaho Transportation Department before Coltin was killed. “It’s a dangerous situation. It’s a nuisance. It’s ugly. It could start a fire,” he said he told the agency.

ITD responsible for maintaining roadway

Many people suspect road salt is killing the trees, but ITD and a tree expert have said that’s likely not the case.

“I don’t think we put out enough salt to kill trees,” Copeland told the Statesman.

Janusz Zwiazek, a University of Alberta tree physiologist who studies the impact of salt on soil and trees, told the Statesman it’s “very unlikely” the salt load is high enough to kill trees en masse.

Experts aren’t sure why the trees are dying, but forest health staff from the Forest Service have said factors can include drought, habitat issues and beetles.

Coltin lost his life near mile marker 77, Boise County Sheriff Scott Turner told the Statesman. That’s in Banks, a small community north of Horseshoe Bend.

“It was definitely extremely tragic for the family, obviously, and the first responders,” Turner said. “It was a pretty tough crash.”

In Coltin’s case, the top of a dead tree hit the car in which he was riding in the passenger seat, according to an incident report written by Deputy Sheriff Stacy Attinger. It struck Coltin on the top of his head and lacerated his arm. By the time Attinger responded to the scene, the teen had died and was covered with a sheet in the passenger seat.

The sheriff’s office system indicates that it took Attinger 22 minutes to respond after a call came in, Turner said, but she likely arrived sooner; dispatchers often delay logging times when things are busy, and there were multiple accidents that day. Garden Valley Fire Department personnel reached the scene before the sheriff’s department, he said.

The day after Coltin died, another tree fell across the road north of Banks because of a rock slide, Turner said. ITD blocked a lane and cleaned it up, he said.

In an obituary the family published in the Statesman, they described Coltin as an aspiring cowboy who rode bulls in a school rodeo. He loved the outdoors, the obituary said, and liked to tinker with his dirt bike, cook, sew and ride horses. At the time of the incident, he was about to finish eighth grade at Payette Lakes Middle School in McCall.

“He had a heart of gold,” his family said in the obituary.

Coltin’s grandfather, Joe Gallagher, declined to comment on behalf of the family members and said they weren’t ready to talk about the traumatic experience.

“I don’t think anybody really has responsibility for this incident,” Copeland said. “I think this was an act of God.”

Jeffrey Hepworth, a Boise personal injury and wrongful death attorney, told the Statesman it should be obvious that the state has a responsibility to keep public highways safe. If the state monitored and maintained trees regularly, they would assume the legal duty to care for them, he said. Planning to cut down trees and not doing it is also evidence of responsibility, he said.

The Transportation Department has an easement that allows it to maintain an area of about 40 feet from the center line of Idaho 55 on the uphill side and to the high water line of the Payette River downhill, Copeland said. ITD is supposed to keep the road safe but works “in conjunction” with the U.S. Forest Service on cutting down trees, he added.

The tree that killed Coltin appears to be on Bureau of Land Management property based on an agency survey, the agency’s spokesperson, Serena Baker, told the Statesman. BLM doesn’t have a role in taking care of its land along the highway, she said. “It’s (the Idaho Transportation Department’s) responsibility to maintain that right-of-way,” she said.

Coltin’s death ‘directly’ tied to tree removal

This month, ITD and the Forest Service started removing trees between mile markers 72 and 79. Some trees were already reduced to piles of wood chips when the Statesman visited the site. Dozens more were marked with an orange X.

That July day, Sam Lewis, the Forest Service feller boss for the project, walked up to a large tree with bug holes and dead branches. With an ax, he struck the ponderosa pine a few times, and cut his chainsaw into the bottom of the trunk as sawdust flew. The road was temporarily blocked to cars so that the tree could fall into the road without hurting anyone.

Will ITD do anything differently moving forward?

Spokesperson John Tomlinson told the Statesman the agency is not planning any new initiative to identify dead trees or cut them down more quickly. They also still don’t know what’s killing the pines on Idaho 55, he said, and have left that up to the Forest Service.

But the agency is moving forward with a $317,000 contract to remove more trees between Horseshoe Bend and Banks. That’s separate from the current Forest Service work and it still needs to go through a public comment period that ends July 31 and a board vote sometime in the next couple of months before work can start, he said.

Lewis, who was at the scene directing traffic the day Coltin died, said his death “directly ties to why we’re here today.” He thought it had expedited the project, he said; the tree that killed him was one of the first to go.