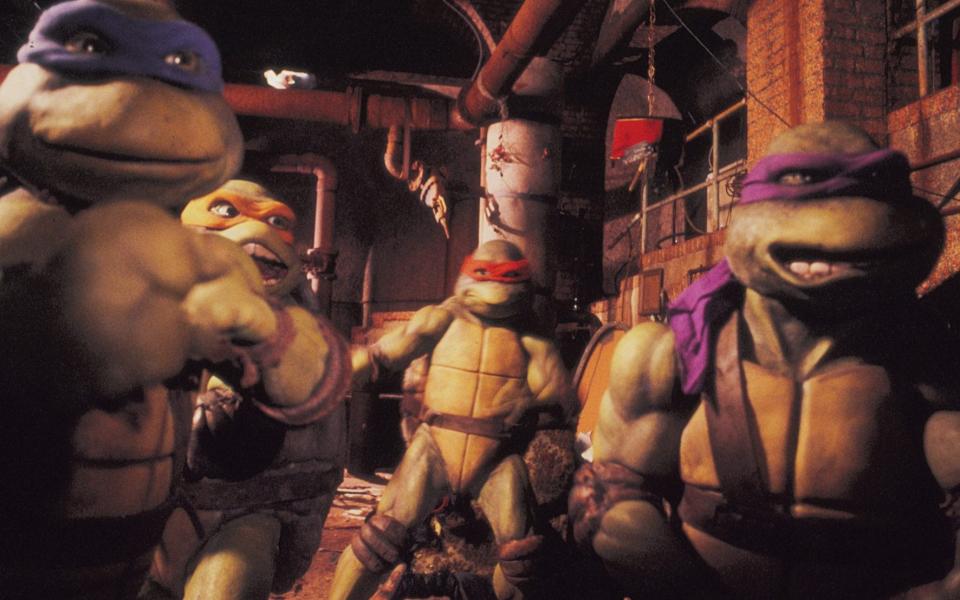

Teenage mutant ninja turtles bought during 90s craze now overwhelming sanctuaries

The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles craze led thousands of children in the Eighties and Nineties to convince their parents to shell out for a pet terrapin of their own.

But teenagers grow up – and so do turtles. Now Britain’s empty-nester parents are searching for ways to rehome the terrapins, which are invasive in the UK and can grow as big as a dinner plate.

Thirty years ago the comic book, television and film series sparked a boom in terrapin adoptions, but now hundreds are ending up in animal shelters, conservationists have warned.

Some have even been released by frustrated owners into the British countryside, where they are not well-adapted to live and may also be causing environmental damage.

Native to the southeastern US and Mexico, terrapins include several small species of turtle. Varieties including Red-Eared Sliders, Yellow-Bellied Sliders and Cumberland Sliders have been found living in UK lakes and ponds.

Andy Ferguson, a herpetologist at Lincolnshire Wildlife Park, said the park’s National Turtle Sanctuary had more than 200 of the reptiles and had taken them in from as far away as Inverness.

He said that in around a fifth of cases, terrapins – which can live for several decades – were coming from homes where children had left to go to university and parents were left holding the turtle.

Terrapins are work-intensive pets, requiring a heated environment, frequent cleaning, and specialist equipment and food.

“The parents are a good bit older now and lugging tanks of water and things like that is not really something that they can do that often,” he said.

The centre has built eight ponds to keep up with demand and is planning to build more. It has a Natural England licence for a thousand terrapins but doesn’t advertise for fear of becoming overwhelmed.

“I could jump on Facebook today and do a post about an incoming turtle, and then by tomorrow I could have 10 emails.

“So trying to keep up with the numbers versus the ponds that we're building, that's the hardest game,” he added.

The centre’s latest project is to rehome turtles found living in a lake in Black Park, near Wexham, Buckinghamshire, using humane traps imported from America.

So far eight terrapins have been removed from the lake using the traps.

Some species of terrapin are native to Europe but Britain does not have any native breeds. The animals are not well-adapted to cope with the cool, damp climate and may suffer from health problems. Releasing them is illegal under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981.

They may also be affecting Britain’s wildlife and ecology, though experts have said further study is required to measure their impact.

In Black Park they eat plants as well as amphibians and their larvae, and were removed in order to preserve vegetation newly introduced to stabilise the banks of the lake and reduce erosion.

Councillor Clive Harriss, of Buckinghamshire County Council, said they were disrupting the ecology of the lake.

“They start eating all the dragonfly larvae, tadpoles, birds’ eggs, depending on how big they are.

“So we end up with a situation where the eco balance within the park has been destroyed, and we start losing some of the vegetation that is so attractive, but also some of the species that people come to see. They've become a real problem.”