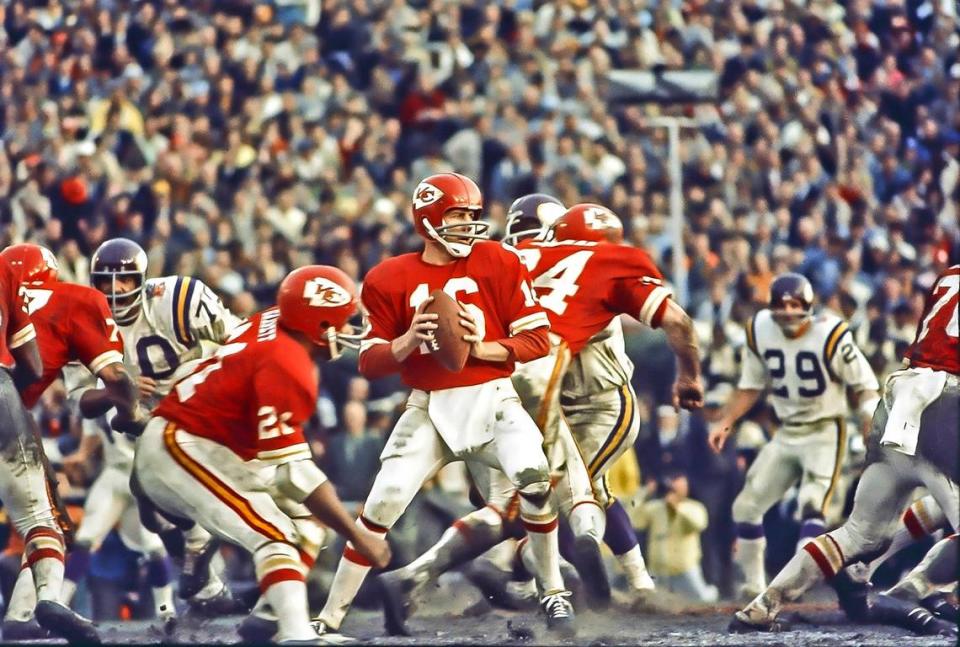

Remembering Super Bowl IV, from multiple Chiefs Hall of Famers to 65 Toss Power Trap

Editor’s note: Super Bowl IV, played 50 years ago this month between the Kansas City Chiefs and Minnesota Vikings in New Orleans, was a milestone in many ways.

The Chiefs won the game, cementing that team in franchise lore forever. In 2010, then-Star sportswriter Randy Covitz wrote the following piece from Miami, where the Indianapolis Colts and New Orleans Saints were set to square off in Super Bowl XLIV on the 40th anniversary of Super Bowl IV.

At game’s end that night, it was Len Dawson, the Hall of Famer and Chiefs legend, who presented the Lombardi Trophy to the victorious Saints on the field after they beat the Colts.

We’re republishing this piece now as the Chiefs get set to face the San Francisco 49ers 10 years later, 50 years after Super Bowl IV, in Super Bowl LIV — Kansas City’s first Super Bowl since Super Bowl IV on Jan. 11, 1970.

MIAMI GARDENS, Fla. — Tonight, Len Dawson will be in the Super Bowl spotlight again.

Dawson, the Chiefs Hall of Fame quarterback, will hand the Vince Lombardi Trophy to the winners of Super Bowl XLIV — 40 years after he and his Kansas City teammates helped spark the transformation of this game from curiosity to national holiday.

“To think we were part of that and what jump-started what this is all about today...” reflected Dawson, the game’s MVP when the Chiefs shocked heavily favored Minnesota 23-7 on Jan. 11, 1970, in New Orleans.

“No one would have dreamed in those days it would be this kind of spectacle.”

Two people did have an inkling that the Super Bowl had the possibility of captivating America. Ed Sabol, founder of NFL Films, and his son, Steve, came to Super Bowl IV with telephoto lenses, a wireless microphone they affixed to Chiefs coach Hank Stram, and a vision of how modern technology could bring the game closer than ever to a burgeoning audience.

Stram, always the showman, put on as riveting a performance as his players did. His exhortations to Dawson and his teammates to “Matriculate the ball down the field, boys” ... “Way to pump it in there, Lenny” and then sending in the most famous play call in NFL history, “65 Toss Power Trap,” punctuated the Chiefs’ victory and popularized the Super Bowl beyond anyone’s expectations.

“That’s the game that made the Super Bowl,” said Steve Sabol, now president of NFL Films.

Indeed, from there the Super Bowl mushroomed into the biggest sporting event of the year. The 10 most-watched television programs in history are all Super Bowl games, with fans just as interested in the high-dollar ads and the highly orchestrated pregame and halftime shows.

Super Bowl IV was at the epicenter of a changing professional football landscape. The Chiefs’ dominance of Minnesota, following the New York Jets’ 16-7 upset of Baltimore in Super Bowl III, gave the upstart American Football League the credibility and legitimacy it needed going into its merger with the National Football League in fall 1970.

“Super Bowl III with (Joe) Namath, that was great theater,” Sabol said. “But in the public’s mind, the NFL was still superior, and that was borne out by the betting line; the Vikings were 13-point favorites. In the public’s mind, there wasn’t any parity between the leagues.

“Because of the fierce physical beating the Chiefs put on the Vikings, this was the game that made the Super Bowl a legitimate competition.”

The success of the Jets and the Chiefs in those two Super Bowls convinced the staid NFL that there was another way to play the game. The AFL game was more creative on offense and more innovative on defense, and had one of the first great soccer-style kickers in Jan Stenerud.

“At one time in the NFL, it was almost a rule that you all played the same defenses and you used basically the same variations of formations,” said former NFL coach Dick Vermeil. “And along comes Hank Stram, and he’s doing things differently and successfully.”

The AFL was also more progressive in scouting, signing and playing African-American players than the NFL. Forty-five percent of the Chiefs’ players were black, as opposed to the Vikings’ 24 percent. Super Bowl IV hit home with the old-line NFL teams that to compete in the merged league, they must open their doors to more black players and abolish the unspoken quota system.

“It was a statement of opportunity to perform, showing that where you came from was not a question as long as you had the ability to compete,” said Willie Lanier, the first black middle linebacker in NFL history and one of six players from that Chiefs team (along with Stram and owner Lamar Hunt) in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

“If you look back at this being 2010, and that was 1970, all the changes that have come since then, all the diversity we talk about now, be it coaches, be it the president of the United States, nearly half a team showed a different population able to express itself in the biggest game being played.

“That set the stage for so many things, not just football.”

There have been plenty of famous plays in pro football history. Alan Ameche’s overtime touchdown run in the 1958 NFL championship game ... Bart Starr’s quarterback sneak in the 1967 Ice Bowl ... The Catch by Dwight Clark in the 1981 NFC championship game ....

Few people, though, other than the participants, know the names of those plays.

But “65 Toss Power Trap,” which broke open Super Bowl IV, was one of the game’s signature plays. It represented the power of the Chiefs and the bravado of Stram, and was perpetuated by the Sabols’ pictures and sound.

The Chiefs led 9-0 midway through in the third quarter on the strength of three Stenerud field goals and an overpowering defense when they faced third and-goal at the Minnesota 5. Though a pass appeared in order, Stram sent wide receiver Gloster Richardson into the game with a running play.

“Gloster, tell (Dawson) 65 Toss Power Trap,” Stram said. “It might pop right open.”

Dawson normally called his own plays and, like all his teammates, was unaware Stram was miked. He was surprised at the coach’s selection.

“We hadn’t even practiced it,” Dawson said of the play, an inside run to the left by Mike Garrett. “It wasn’t even in the game plan.”

Dawson took the snap and spun toward fullback Robert Holmes, who appeared to be running wide left. Left tackle Jim Tyrer pulled left, convincing Minnesota end Jim Marshall that was the direction of the play. Right guard Mo Moorman pulled to the left, trapping tackle Alan Page and clearing the path for Garrett.

Garrett bolted through the line of scrimmage, waited for tight end Fred Arbanas to wipe out middle linebacker Lonnie Warwick and pranced to the goal line.

“I told you that baby was there!” Stram chortled on the sideline. “65 Toss Power Trap. ... The coach pumped one in there.”

A depiction of that play will be carved in stone in the sidewalk in front of the Founder’s Plaza at the refurbished Arrowhead Stadium, where fans will follow Garrett’s footsteps to the end zone, where he jumped into the arms of wide receiver Otis Taylor.

Every year when the Super Bowl rolls around, Garrett’s wife, Suzanne, looks forward to seeing the NFL Films’ production of Super Bowl IV.

“She’s the first to say, ‘They’re going to run that trap play, aren’t they?’ “ said Garrett, now the athletic director at the University of Southern California. “I say, ‘Honey, they’re going to run it.’ After all these years, that play still rings in people’s minds. I never expected that to be the case, but Hank was so colorful, and with him yelling out ‘65 Toss Power Trap,’ it crystallized it in everybody’s mind.”

Indeed, the melding of Stram’s chatter with his players executing his plays appealed to casual fans as well as football aficionados.

“People responded to that and to the film,” said Michael MacCambridge, author of “America’s Game,” a definitive work on NFL history. “For serious fans who studied the game closely, there was a glimpse of the strategy they’d never seen before. For non-fans or casual fans, there was enough color and comedy in Hank’s repertoire that it was captivating to watch.”

Once the Chiefs had a 16-0 lead, their defense took over, punishing Minnesota quarterback Joe Kapp, who gamely played despite having to leave momentarily with a separated shoulder.

Kapp and defensive end Carl Eller said the Vikings, who went 12-2 in the regular season, did not underestimate the Chiefs, whose owner, Hunt, had outbid the more tight-fisted NFL teams for talent.

“If you look at the AFL teams we played against, look at the size of them,” Kapp said. “They were bigger than us, faster maybe, they had a bigger payroll, but we weren’t 13 points better. That was overstated. If we were not as good a team as we were, they would have wiped us out.”

The Vikings managed to draw within 16-7 with a third-quarter touchdown, but the Chiefs pulled away with another signature play captured by NFL Films -- Dawson’s quick hitch to Taylor, who shook off cornerback Earsell Mackbee and high-stepped his way 46 yards down the sideline as Stram chattered to anyone within earshot, “That’s it, boys, that’s it!”

“The majesty of Taylor going down that sideline and just destroying that Vikings secondary and strutting down for that touchdown, to me, that epitomized the AFL,” said Bob McGinn, author of “The Ultimate Super Bowl Book.”

NFL Films cameras also captured the poignant scene when Stram sent backup quarterback Mike Livingston into the game so Dawson could get a curtain call.

“Thataway to go, Lenny, you done good, kid,” Stram told Dawson, who had endured a draining week as well as a difficult season.

Dawson, who had missed seven games during the regular season because of a knee injury and whose father died unexpectedly during the season, was mentioned in an NBC news report during the week of Super Bowl IV, linking him and five other players to a Justice Department sting into sports gambling.

The story proved false. Dawson was never subpoenaed, and the story died.

After the game, President Richard Nixon called Dawson in the locker room to congratulate him on the game and exonerate him in the probe, to the relief of Dawson, who had insisted there was no truth to the report. It was the first presidential call to a locker room, a tradition that is now part of Super Bowls, World Series and other championship events.

So tonight, President Barack Obama, one of 1 billion viewers in more than 230 countries who will have watched Super Bowl XLIV, will call the winning locker room.

And Len Dawson will be there to relive the moment.