Ten years later: A family destroyed

Ten years ago Wednesday, 40-year-old Karen Dickson died in the crash of USAir Flight 427. Her death was quick, the destruction left behind incomprehensible.

In all, 132 people perished when the Boeing 737 nose-dived into a Hopewell Township hillside.

But for Karen's husband and two young children, the horror of that day never ended. Like the malfunctioning rudder that caused the crash, Karen's absence pitched her perfect family into a slow tailspin.

Her husband, Dennis, wallowed in beer and bourbon, trying to numb the agony of losing his best friend. He quit working and blew through the $2.1 million he received in compensation from USAir. Their children, Leah and Eric, then 14 and 10, were left with an ever-flowing river of cash and no rules. They skipped school and took drugs.

Family members tried to intervene. Karen's mother cooked and cleaned and attempted discipline. Dennis' brothers and sisters offered to raise the children until Dennis could find a way out of his free fall. He refused. No one would be taking away the only pieces he had left of Karen.

So the family fell apart. Leah became addicted to OxyContin. Eric ended up in jail.

The money dried up. Dennis' disapproving parents stopped speaking to their grandchildren. And Dennis continued to drink until his body could take it no more.

He died in January of cirrhosis of the liver. He was 50.

Leah, 24, and Eric, 20, were left orphans, staring into a cold world of family conflict and petty rumors about what they had become. But they took quiet comfort in knowing their father was finally where he had longed to be for all of those years - with Mom.

In ancient Chinese philosophy, there is a black and white circular symbol called the yin-yang. The yin is the black half of the symbol with a white eye; the yang is the white half with a black eye. Together they are responsible for all that happens in the world. They are opposites, and yet they cannot exist without each other.

That was Karen and Dennis Dickson.

Karen grew up in the Glenwillard section of Crescent Township, where everybody knew their neighbors' names and their neighbors' business. Her father, William Waldron, the service manager at a Cadillac dealership, liked to drink too much bourbon. Her mother, Mary Waldron, was devoutly Catholic and counted her daughter as her best friend.

Karen's only sibling was her brother, Bill, older by seven years. But she and neighborhood friend Kim Hudie spent so much time together, they might as well have been sisters. They met in first grade.

The girls rode the school bus together, walked to the corner store to buy milk for their mothers together, went on vacations together and, when the summer sun beat hot enough, lounged by the pool together.

Karen wasn't much of a swimmer, but she looked good in a bathing suit.

She was tall and curvy with shiny golden hair that spilled halfway down her back and a smile that could have melted glaciers. Except for a little lipstick, she never wore makeup. She didn't need it.

Dennis called her a knockout.

An A student, Karen was every bit as smart as she was pretty, and sweet, too. Friends say she probably never had an enemy in the world. All of the boys wanted to date her, and all of the girls wanted to be her best friend.

Dennis was more of an acquired taste. He talked too much, laughed too loud - usually at his own jokes - and offended people with his needling frankness. But his marshmallow heart, soft and sweet, won over good-girl Karen.

She kept him straight. He kept her giggling. They started dating their junior year of high school, just before prom.

Dennis lived only a few miles from Moon Area High School on Beaver Grade Road and was raised under the stern eyes of a steamfitter named Paul Sr. and a no-nonsense homemaker named Lula, though everyone knows her by her childhood nickname, "Pete."

Dennis, 6-foot-3 and 235 pounds with dark hair and a square chin, was the only one of his seven siblings to play football, which made him his father's favorite.

High school football coach Rip Scherer said Dennis could have played any position, but his real talent was punting. With legs like tree trunks - he had a 34-inch waist but wore size 38 pants to make room for his thighs - Dennis could clobber the football. He had so much hang time, occasionally it looked as if the ball would never come down.

He was the best punter Scherer ever coached and, to this day, the best he's seen.

He was so good that, after graduation in 1971, Pittsburgh Steelers scout Dick Haley invited Dennis to Montour High School's stadium for a tryout.

Afterward, Haley pulled Paul Sr. and Dennis aside. Dennis had the talent, and he had just kicked for more distance and hang time than any punter in the National Football League that season, but he needed more experience.

Play some college ball, Haley told him, and then come back and see us.

Paul Sr. was elated. Dennis already had scholarship offers from a half-dozen schools, including a full ride to Syracuse University. But Dennis didn't want to go to New York or anywhere else without Karen.

He declined every offer.

Meanwhile, Karen, whose father had given her money to pay for college, shocked everyone when she announced she wanted to be a nurse. She was afraid of needles. She had best friend Kim Hudie go the doctor's office with her when she needed a shot.

"It's going to hurt, I know it's going to hurt," Karen would cry as they waited.

"You baby," Hudie would tease her.

Karen chose Sewickley Valley Hospital School of Nursing for her schooling and lived in its dormitories, on the Moon Township campus of Robert Morris College.

She was an exemplary student, a critical thinker and problem-solver who always made eye contact with her lecturing teachers. But what really set her apart from her classmates was her gentle spirit.

It struck Karen's clinical instructor Faith Savasta as she watched her young student sit at the bedside of a dying young mother, holding her hand and shedding tears with her and her family.

"She was so gentle," Savasta said. "She had a maturity beyond her years."

Dennis did not. When he finally decided to attend Potomac State, a junior college in Keyser, W.Va., he was more interested in football and beer than teachers and books. Instead of studying, Dennis would dig out the boxing gloves his dad had given him and challenge the guys in his dorm to matches. They sparred until they were bleeding or laughing, or both.

By the time Karen graduated from nursing school in 1974, one of the top students in her class of 34 and winner of the "Outstanding Nurse" award, she had already made plans to attend the University of Miami and earn a bachelor of science in nursing.

Miami had a unique program that allowed its nurses to live in dorms and go to school for free in exchange for working at Mount Sinai Medical Center, a nationally acclaimed teaching hospital.

It was a four-year program, but Karen managed to complete it in two, testing out of half of her required classes.

While Karen worked and went to class, Dennis, who couldn't stand to be without her, had left Potomac State to follow her to Florida and worked as a welder. They were happy, but poor. On Thanksgiving, they sold their blood for money to buy a turkey.

One night, Dennis took Karen out to dinner and slipped a tiny diamond ring onto her slender finger.

They married on Aug. 21, 1976, at St. Catherine Catholic Church in Crescent Township. Karen dressed in the church basement, pulling her lacy white dress over her head and pushing pearl earrings into her lobes.

Dennis dressed in his bedroom at home, blasting Three Dog Night - his and Karen's favorite band - while he buttoned his ruffled shirt and straightened his bow tie.

At the reception that night, Karen's maid of honor, Hudie, gave a speech about friendship. Karen and Dennis would live a long, happy life together, she said, because they were best friends.

Their wedding song, "Pieces of April," played. Glasses clinked and the newlyweds danced into the best years of their lives.

April gave us springtime and the promise of the flowers

And the feeling that we both shared and the love that we called ours

We had no time for sadness, that's a road we each had crossed

We were living a time meant for us, and even when it would rain we would laugh it off.

I've got pieces of April, I keep them in a memory bouquet

I've got pieces of April, but it's a morning in May.

Three Dog Night

Pieces of April

During 18 years of marriage, Dennis Dickson and Karen Waldron experienced plenty of rainy days, but they always managed to laugh them off. They were best friends, and their love never wavered.

Through it all, Karen was the guiding force. She was the pilot; she kept the marriage aloft.

If Dennis was the jokester, Karen was his straight man. He was the life of the party. She was the quiet planner. Dennis never made a major move without consulting Karen, and she always had the last say.

For the first few years, they lived in various apartments in the Coraopolis area. Then they moved back to Karen's old Glenwillard neighborhood, buying a split-level house on Walnut Street.

It wasn't the fancy house in Sewickley that she dreamed of one day owning, but it was a beginning and a safe neighborhood to raise children, plus it was close to her parents.

The small, close-knit community knew and adored Karen, with her perpetual smile, gentle manner and girl-next-door good looks. They grew to like Dennis.

She taught nursing at Ohio Valley General Hospital, where her students loved her. One told Dennis' mother that Karen was the only reason she made it through nursing school.

Dennis followed in his father's steamfitting footsteps, working at construction jobs in the tri-state area, with most of his work coming from the mammoth electric plants at Shippingport.

They were making good money, enough to start a family.

Leah Katherine Dickson was born April 15, 1980. Her brother, Eric Jon Dickson, was born four years later, on April 24. Their parents called them "Stinky" and "Dude."

With two children to rear, Karen and Dennis got into parenting with a relish.

There were picnics at Raccoon State Park, excursions to the Waldron family cabin in Cook Forest, meatloaf dinners at the Dicksons, swimming at Chanticleer swimming pool in Crescent, boating on the Youghiogheny River, summer vacations to Myrtle Beach, S.C., and Ocean City, Md., and snowmobiling in the winter. Karen and Dennis had matching black snowmobiles.

Dennis faithfully recorded family doings on video: Leah and Eric throwing snowballs in the back yard; Eric as a bow-legged toddler running in Cook Forest with Dennis running to catch him before he got to the road; and hours of the kids painting Easter eggs in the kitchen.

Karen and Dennis also had their time apart from the kids, but they set rules. They had girls' nights out and guys' nights out, but weekends were for the family.

Dennis loved to golf and had a gentle touch with the putter. He also liked Jim Beam and Coke, a bone of contention with Karen, who kept his drinking in check. He was a social drinker in those days.

Karen went to slumber parties with the Dickson family girls. She and Dennis were complete opposites, she admitted during one sleepover, but she adored him; he was not only a great father, but also a great lover.

Every Friday, the family went out to dinner. Hoss's Steak and Sea House was their favorite.

Saturday was cleaning day. Leah and Eric cleaned their rooms while their parents did chores around the house.

On Sundays, Karen took the kids to St. Catherine's with her mother. Dennis, a Presbyterian, usually stayed at home, but always made the holiday services.

Friends said they were the perfect family. Leah described it as the "Brady Bunch." For Eric, it was like "Leave It to Beaver."

They had arguments, but Leah and Eric can't remember their parents ever having a full-blown fight in front of them.

Leah was a chubby little girl with short brown hair and a mischievous gap-toothed smile who inherited her dad's personality. She loved her little brother dearly, but enjoyed tormenting him.

She would lock Eric in the bathroom because she knew he was afraid of the dark, luring him into playing a kid's game called "Bloody Mary." It involved twirling around in the blackness and peering into the bathroom mirror to see the ghostly, spinning reflection.

Then she would slam the door shut and hold it until he cried to be let out.

Eric, on the other hand, was gentle like his mother. He was the baby, and mother and son were close. She would rub his back before he went to sleep at night and let him brush her hair. He was a quiet, sensitive towheaded blond who sang songs to Karen and brought his grandmother purloined daffodils from a neighbor's yard.

Mary Waldron can still see Eric - a little white-haired boy proudly walking through her yard with an Easter flower in his hand.

Both kids played sports when they were younger. Leah played soccer and Eric soccer, football and baseball.

Dennis and Karen attended every game. Karen brought orange slices for the soccer teams to eat at halftime. Dennis stood on the sidelines, videotaping games and yelling instructions, "Leah, get in there!" or "Eric, hit somebody!"

Karen, who had quit her job at the hospital just before Eric was born, took a new job in 1985 as a supervisor for Intracorp, a managed-health-care firm in North Fayette Township. The job paid very well, and the family's finances improved considerably.

In 1986, Karen and Dennis bought a house for her parents, just four doors from theirs. William Waldron had cancer, and Karen wanted to be close so she could take care of him. He would die five years later.

Mary Waldron, in turn, was close enough to help her daughter's family. She baby-sat while Karen and Dennis were at work, cleaned house, washed clothes and made dinner.

Around 1988, construction work in the area began to dry up, and Dennis had to travel farther for jobs. It was time for a change.

He and Karen bought the Essex Beer Distributor in North Fayette for two reasons: The business was steady, and Dennis could make his own hours.

It allowed him to watch the kids when Karen was at work. He often took Leah and Eric with him when he made deliveries of chips and beer to local bars.

At Intracorp, Karen was moving up the ladder. Diane Redington, her boss, trusted her with the most important projects because her work always exceeded expectations.

But the projects meant long hours. She had to travel. Philadelphia was a common destination; on occasion, she flew to Chicago.

Eric and Leah hated when Karen went on business trips. They cried every time she had to leave overnight. And Leah had nightmares. One night, she dreamed Karen died in a plane crash, and that made the separations even more frightening.

Redington, who traveled with Karen a lot, remembered Karen always brought gifts home for her kids. One time, she searched for hours to find a coonskin cap for Eric and was thrilled when she finally found one.

As Leah and Eric grew older, Karen started scaling back at work. She declined promotions to spend more time at home. Leah and Eric were more important, Karen often said. She thought they would need more of her attention when they became teenagers.

She enrolled at Carnegie Mellon University to earn a master's degree. She told Dennis' sister that a teaching job at one of the local universities would give her more time with Leah and Eric.

She graduated in May 1994 with a master's in public management. A picture taken after the commencement shows a beaming Karen, her long hair now cut in a business woman's bob, in her cap and gown with one arm wrapped around her diploma and the other around Leah.

The future couldn't have been brighter.

At work, she was heading up a special project. It would mean one last trip to Chicago.

'Did Karen get on that plane?'

The morning of that Chicago trip was like any other. Karen roused the children early and got them ready for school. She kissed everyone goodbye and told them she would be home that evening.

I'll catch an earlier flight if I can, she promised Dennis.

On her way to the airport, Karen passed Leah, who was standing at the corner waiting for the school bus. She beeped the horn on her old car and waved.

Just a few minutes later, she passed her brother on Flaugherty Run Road. He recognized her car and raised a hand from his steering wheel.

Karen was traveling to Chicago for meetings about her latest health insurance project. The meetings lasted all day, and Karen had to settle for her scheduled flight on a Boeing 737, the most widely used jetliner in the world.

This particular 737 - N513AU - had already taken off and landed six times that day. In Chicago, USAir mechanics gave the plane a once-over and sent it on its way. Designated Flight 427 to Pittsburgh, N513AU left its gate at 6:02 p.m. and was airborne by 6:10.

It was a spectacular day for flying. The evening was warm and clear, with only a few cotton-ball clouds dotting the blue sky. Capt. Peter Germano and his first officer, Charles Emmett III, switched on the autopilot and let N513AU fly itself.

Karen was in 5F, a window seat on the right side of the plane, three rows behind first class. She was sitting next to a pregnant Paula Rubino-Rich, 29, of Poland, Ohio. The two women might have chatted about motherhood during the flight, but Mary Waldron doesn't think so. She desperately hopes her daughter was sleeping. Karen was always tired.

Shortly after 7, and only a few miles from the runway at Pittsburgh International, the pilots saw the first signs of trouble.

They had just turned the plane into a gentle bank when the left wing dipped slightly and inexplicably.

"Whoa," Germano said. Emmett grunted.

For a moment, the plane righted itself. But then it dipped again, this time at a steeper angle, and began falling from its assigned altitude of 6,000 feet.

Germano and Emmett clicked off the autopilot. Its disconnect horn blared in the cockpit.

The plane was flying low and fast then, growling hoarsely as a plane does just before takeoff. It zipped crookedly over houses, rattling shingles.

The pilots, swearing and grunting, grabbed the controls and tried to pull the plane's nose up. Instead, it tipped vertically, so the nose was pointing directly at a wooded hillside, and began to dive.

On a soccer field behind Green Garden Plaza in Hopewell, 12-year-old midfielder Katelyn Stroup and her teammates from the Moon Area Soccer Association watched in horror as the plane twisted out of the sky.

A few miles away at Beaver Lakes Country Club, where Beaver County Coroner Wayne Tatalovich and his wife, Val, were hitting golf balls, Val's friend Norma Figley began to scream.

"Wayne! Wayne! A plane! A plane!"

The sickening thud of an airliner plowing straight into the earth at 300 mph rocked Hopewell. Tatalovich looked up just in time to see a cloud of black and gray smoke mushroom into the sky.

He turned to Figley.

"How big was the plane, Norma?"

"Big, Wayne. I think a USAir plane."

Tatalovich ran for his Jeep.

—

Ten miles away, in the split-level house on Walnut Street, Leah and Eric had just finished eating dinner with Grandma Waldron. Leah changed into her pajamas and settled on the couch in front of the television. She still had math homework to finish, but she needed Karen's help. It was word problems, and Karen was good at those.

Eric waited for his mother outside, crouching before a box car Dennis had built for him. He was painting orange flames when he heard the screams of passing firetrucks.

—

Paul Dickson Sr. was sitting at his kitchen table in the house where Dennis had grown up when his daughter-in-law rushed in. A plane had crashed in Hopewell, she told him.

"Geez," he said, turning to his wife. "Karen was due in about that time."

Pete picked up the phone.

—

Dennis' little sister Terri was standing on the lawn of her Brighton Township home, watering the plants when her housemate, Mary West, pulled into the driveway.

West had already heard the news on her car radio. Details had been sketchy, but reporters said a commercial airliner had crashed. She was worried Terri's sister, Lois, a flight attendant for United, was on the plane.

"Call your mother," West said.

The two ran into the house, but before Terri could pick up the phone, it rang. Pete was on the other end.

"Karen might have been on that plane," she told Terri.

—

Debbie Barone, Dennis' younger sister by two years, was on her way home to the Moon Township neighborhood of Twin Oaks when her cell phone rang. It was Pete.

Debbie listened to her mother's terrible words and hung up, stunned.

She made it home, but she doesn't remember how.

—

Diane Redington returned home from dinner with a co-worker to find her husband watching television. News of the crash flickered across the screen. Redington froze.

That's Karen's plane, she told her husband. She was almost certain.

She frantically dialed her colleagues in Chicago.

"Did Karen get on that plane?" she asked them.

She did.

—

Karen's best friend and maid of honor, Kim Hudie, who had married and moved to Las Vegas, was on her way to her son's second-grade open house when she heard about the plane crash in Hopewell.

Hopewell?

She paused for a moment.

Thank God I don't know anyone who flies to Chicago, she thought.

—

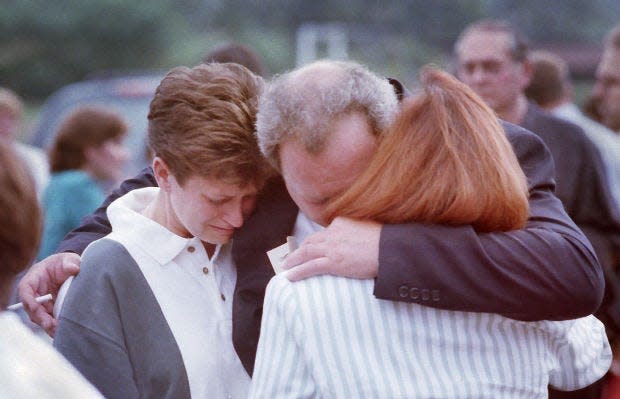

Within hours of the crash, a crowd of family and friends had gathered at Dennis and Karen's house. They hovered around the television waiting for more details and lingered in the kitchen, where a calendar confirmed their fears.

Penned into the box for Sept. 8, in Karen's handwriting, was a single word: Chicago.

Dennis couldn't believe it. He folded his heavy body into a chair and buried his face in his hands.

He had gone golfing with a buddy that afternoon and stopped at a local bar for a few drinks after finishing the round. He heard about the crash on the bar's television, but ignored it. He was sure Karen was flying in from Philadelphia that night, not Chicago.

Now his mind was wildly sputtering all of the possibilities. She could have taken a later flight. If she were on Flight 427, maybe she was among the survivors.

While Dennis weighed the odds, Leah sat on the couch, numb. She was 14, and her mother was gone. She didn't have a voice or tears to cry.

Eric stood at the window, peering down Walnut Street. He was waiting for his mother's old car to turn the corner. He was 10, and he didn't understand.

Pete punched numbers into the phone. She had friends at USAir, and she was certain somebody had to know something. But nobody did.

After a while, Dennis' sisters, Debbie and Terri, and Terri's housemate offered to go to the airport. They were hoping to find more information, but when they arrived, they were ushered into a USAir lounge, where others had already begun to gather.

Nearly two hours passed without answers from the airline. At 11 p.m., Dennis arrived with younger brother David.

Two more hours passed.

At 1 a.m., USAir President Seth Schofield appeared in the lounge with a spokesman at his side. The room fell deathly silent.

There are no survivors, they told the crowd.

A woman standing near Dennis began to howl and sob, her screams ripping through the room like a knife. Her brother was on the flight.

Dennis stared at her for a moment with empty eyes. Then he wrapped his bulky arms around the stranger and held her close.

—

When he got home, Dennis grabbed his older brother, Larry, a Kennedy Township cop, and begged him to go to the crash site. He wouldn't believe his wife was gone until he had proof.

"Larry," he said. "Find Karen."

Then Dennis scooped his children into a suffocating hug.

"It's going to be all right," he told them.

On their first night without Karen, Dennis, Leah and Eric all climbed into Leah's bed and went to sleep.

A loaded gun

Larry Dickson had seen plenty as a police officer, but nothing prepared him for the horror of the Hopewell crash site. Even 10 years later, he can barely talk about it, and he avoids Green Garden Road, which runs nearby, at all costs.

But on Sept. 9, 1994, Larry donned his uniform and drove to Green Garden Plaza. He didn't want to go, but he felt obligated.

The first thing he saw at the command center was a paramedic who looked enough like Karen to be her twin. The crash site was unlike anything he had ever seen.

The plane and its passengers were in unrecognizable pieces on the ground and in trees, scattered about like a jigsaw puzzle strewn to the wind. The largest piece of the plane was no bigger than a car door. There was no possible chance of finding Karen's body among the smoldering wreckage.

Larry left with a pitiful image branded into his mind: Karen calling out for her husband.

It would be years before he could tell his brother what he saw that day. At the time, he simply urged Dennis not to go there.

For the first couple of days after the crash, Dennis hunkered down at home and waited for a body that never came. His children were there. So were plenty of friends and relatives, who filled the house with so much food that a local appliance store donated a spare refrigerator to help store it all.

The family was in shock. Dennis smoked cigarette after cigarette. Eric kept taking apart his bicycle and putting it back together. Leah cried and cried.

As days turned into weeks, Dennis was obsessed with finding Karen. He visited the airport, haranguing USAir representatives and anyone else who would listen. He helped form a support group made up of relatives of crash victims. Dennis publicly criticized how USAir and crash investigators handled the situation. He felt relatives were not being informed of what was going on.

Nearly a month passed. Finally, a break came during a chance encounter with Val Tatalovich, the coroner's wife.

Among other things, she was in charge of identifying victims' personal belongings that were stored in a hangar near the airport. She happened to be talking to Dennis and noticed his gold wedding band.

I've seen that ring before, she said.

It prompted a search that turned up an identical band. The ring, nearly smashed, was on the third finger of a hand that was attached to a forearm. They were the only pieces of Karen that were found.

At last, Dennis had the proof he so desperately needed.

Crescent Township and St. Catherine's held a memorial service for Karen, and the entire town showed up with scores of people coming from neighboring communities. The throng filled the township fire hall.

They turned out again for Karen's funeral, held at St. Catherine's. There wasn't enough room in the church, and mourners spilled onto the sidewalk. Intracorp closed its local office, and local schools dismissed students early so they could attend.

Karen was buried in St. James Cemetery in Sewickley Heights. Dennis asked his mother-in-law, who owned the cemetery plot, to have her buried deep enough so he could eventually be buried on top of her. He designed her tombstone himself. It's in the shape of a teardrop. Etched into the face are a deer in a grassy bed, an angel with a golden halo and a string of roses. He also left room on the stone for his own name.

Dennis had Karen's wedding band straightened and wore it around his neck on a gold chain. He continued to wear his own on his left hand.

Nearly a month had passed since the crash, and it was time for Dennis to move on. He had work to do and children to raise, but he was lost without Karen.

She was the one who took charge in family emergencies. She paid the bills. She made sure the kids got up for school and kept the house in order. She was Dennis' crutch. Now he turned to bourbon.

When Karen died, Dennis felt he died with her. He lost his faith in God and his ability to care. He simply gave up.

"She's just in a hole," he told people who asked whether he thought Karen was watching from heaven. "No God would let something that terrible happen to someone so good."

For the life of him, he couldn't erase a recurring vision of the last 23 seconds of Flight 427. The image of the plane with Karen aboard, plunging and spinning toward the ground, and the horror inside the cabin, haunted him day after miserable day.

Leah thinks her dad was hounded by the guilt that he had been drinking the night his wife died. Others believe he loved Karen so much that he simply could not live without her.

At first he turned to friends, showing up at their homes at all hours. Then, as time wore on, they saw less and less of him. He didn't want to hear them tell him to stop drinking. He hired a manager at the beer distributor and stopped going to work.

Two months after the crash, Dennis filed suit against USAir, seeking more than $25,000 in damages. Then he waited for the settlement that would come less than one year later.

Through it all, he drank. Half-gallons of Jim Beam a day.

Meanwhile, Leah and Eric were left to their own devices, unsupervised by their dad. Mary Waldron made their meals and continued to keep up the Dickson house, but it was impossible to discipline the kids.

Waldron said she never could be mad at Dennis, even though he shirked his responsibilities. She felt sorry for him. Dennis knew what he was doing, but just couldn't stop.

In the year after Karen's death, Leah's grades dropped. Eric's grades, fine at first, dropped in seventh grade, and he was held back a year.

Both children started spending more and more time away from home. They began to drink Dennis' liquor when he was gone, replacing what they took with water. They also began experimenting with drugs.

Dennis' family and friends repeatedly urged him to seek professional counseling for himself and the kids, but Dennis didn't think they needed it. Leah didn't either.

Karen was never far from their thoughts.

Dennis started a scholarship in her name at Moon Area High School that first year after the crash. As it happened, Katelyn Stroup, who witnessed the plane crash from the Hopewell soccer fields at age 12, was one of the recipients.

He also made wooden plaques in memory of Karen, posting one outside his beer distributor and nailing another to a tree at the crash site.

Intracorp agreed to give Dennis his wife's old desk, and he placed it in a room at home along with pictures and her clothes.

He often visited Karen's grave, and he spent hours at the crash site, going there so often that neighbors came to know his car by sight. Leah went there, too. She said she felt closer to her mother there than anywhere else.

Dennis would spend hours at home, drinking and wallowing in sorrow as he watched old home videos. He was a regular in Moon Township bars, especially the Skylark.

In July 1995, he was at the Skylark when he met a woman named Marcy Cuervo. She was nine years younger and had recently lost her father in a car crash. Both knew the pain of suddenly losing a loved one. They agreed to a date.

They doubled with Dennis' good friend Tom Burgunder and his girlfriend, traveling to Pittsburgh for a Pirates baseball game. The Pirates lost that night. It was an omen for Dennis and Marcy.

USAir settled federal complaint No. 94-1862 in October 1995 during a closed-door hearing in U.S. District Court in Pittsburgh.

The judge sealed the agreement, but Dennis' brother, David Dickson, executor of his will, said Dennis received a lump-sum payment of about $2.1 million. The lawyers got at least 40 percent of that.

In addition, Eric and Leah each got around $300,000. The money was placed in an annuity designed to pay them sums annually through their college years, and then monthly for the rest of their lives after they turn 30. The two won't talk about the amount of the payments.

The money combined with the absence of Karen - the one person who could have pulled the family together - sent Dennis, Leah and Eric spinning completely out of control.

With the money, Dennis didn't have to work. He had time on his hands, time to think about Karen and the demons that were always only one sober breath away.

"It was a loaded gun," Larry Dickson said.

Out of control

On May 25, 1998, Dennis Dickson remarried. He wore leather this time and rode to his reception at Settler's Cabin Park in Robinson Township on a motorcycle.

His parents and brothers, who didn't approve of Marcy or Dennis' indulgent lifestyle, refused to attend the biker-themed wedding, but Mary Waldron was there. She thought Marcy, the daughter of a friend and a graduate of Moon Area High School, might be able to rein in Dennis and the children, just as Karen had.

Dennis' best friend, Paul Burgunder, agreed to be best man.

Burgunder, mustached and built like a bulldog, had known Dennis since their high school football days. They still called each other by their old nicknames. Dennis was Lips, because the coach said he was kissing the players instead of tackling them. Burgunder was Stubby, because the trainers who wrapped his hands before games always had trouble taping his short thumbs.

Stubby wasn't particularly fond of Marcy - "She was no Karen," he said - but he felt Dennis needed the support of his friends if he hoped to turn his life around.

But even after the wedding, Dennis continued his excessive drinking. Friends, Stubby included, pleaded with him to stop. Dennis knew they were right, but he didn't want to hear it. He either laughed their words off or pushed his friends away.

His marriage, rocky from the start, was suffering, too. On the worst nights, he would tell Marcy that he still loved Karen and that she would never be able to replace her. He kept pictures of Karen hanging on the walls and took Marcy to visit her grave and the crash site.

Dennis might have married Marcy, a friend said, but Karen was still his wife.

Her omnipresent ghost haunted and frustrated Marcy. The children say she often turned violent, slamming doors in her husband's face or smacking him.

One afternoon, the neighbors found Dennis, who had apparently tired of the door slamming, ripping all of the interior doors off their hinges and tossing them into his steep driveway. The doors raced down the slope like pucks on ice and piled up in the street.

Leah and Marcy didn't get along much better. Spats between stepdaughter and stepmother escalated quickly to fistfights in the living room. Dennis usually ignored the fights, sitting in his chair and eating popcorn. He wouldn't intervene until they spun entirely out of control. Once, Leah grabbed a knife.

It was a long way from the days of Karen, who would whack her kids' behinds so gently they would run away giggling.

Eric, meanwhile, was falling into a world of drugs. Buoyed by the $50 bills Dennis handed him for lunch money and looking for a way to numb his emotions, Eric was buying and smoking marijuana by the age of 11, selling it in school by the age of 12 and popping OxyContin pills before he got his driver's license.

Dennis didn't reprimand him. He thought his children had suffered enough when Karen died. He didn't want to stifle them with rules or boundaries, and he tried to bandage their wounds with money. He bought so many cars, boats and motorcycles, he had to enlarge the driveway to fit them all.

He took Marcy, the kids and their friends on vacations to Myrtle Beach and the Virgin Islands. He lent money to strangers, once handing more than $20,000 to a man who wanted to buy a hunting cabin. No one ever paid him back.

And in 1999, he bought a $239,900 house in Economy. It sat on two acres and had a pool and a guest house. He thought it would help the kids and his marriage to leave the house on Walnut Street where so many memories of Karen lingered.

It didn't. By year's end, Eric was skipping school, Leah was sniffing OxyContin, and Dennis and Marcy's marriage was racing down the same tumultuous path. One night, after a pool party, Marcy took the car keys from her husband, who wanted to drive to his beer distributor to pick up another keg. Dennis dug an ax out of the garage.

"Give me the keys, bitch!" he yelled.

When she didn't, he took the ax to the sport utility vehicle, smashing the windows and hood, and screaming the same line between whacks.

Leah and Eric, along with Dennis' parents, siblings and friends, all say Marcy only added to the family's lethal mix of alcohol, drugs and sadness with her own substance-abuse problems. And her many calls to the police claiming Dennis had hit her were all fabrications. She's the one who hit him, they say.

Marcy adamantly denies their charges. She married Dennis thinking she could end the madness, she said, but it was already out of her control.

Dennis didn't bother to go home some nights. He would show up at the old house on Walnut, which he had sold to family friends Glenn and Delores Chimile, and ask to sleep in the basement. Other nights he would arrive on Stubby's doorstep, wanting to talk.

No one ever turned him away.

The visits stopped in December 2000, however, when Dennis bought a house in Tarpon Springs, Fla., a popular tourist town with a Greek flavor along the Gulf of Mexico.

Dennis and Marcy bought a $170,000 stucco house on Waterford Circle West, an upscale neighborhood with a park view, where they lived what Dennis called a year-round vacation.

Leah, then 20, stayed in Pennsylvania and lived with friends. After graduating from Moon high school, she worked in spurts, first as an Avon representative and then as a beauty shop receptionist, while squandering her portion of the USAir settlement meant for her college education on friends, cars and drugs.

Eric, who at 16 looked like a slimmer, younger version of his father, split his time between the house in Tarpon Springs and Grandma Waldron's home in Glenwillard.

He was drowning in drugs and skipping school, but somehow managed to earn nearly all A's in his classes before dropping out his junior year.

His teachers and guidance counselors adored him. They thought him well-mannered and upbeat, too kind a kid to have such a life.

But as much as they wanted to, they couldn't save him. Eric's misfortunes and drug addiction followed him everywhere.

One evening in Florida, while he was cooking steak in the kitchen, Eric passed out. He had taken too many methadone pills. The burning meat set off the smoke alarm, which woke a sleeping Dennis. He found Eric on the floor choking and gasping for air. Paramedics managed to save him, though they said another few minutes and he would have been gone.

Legal problems began to plague the young man as well. Though OxyContin was his drug of choice, Eric, at 18, was arrested twice in summer 2002 for cocaine possession and drunken driving. Later that year, he became a suspect in the murder of a friend.

Ron Ford, 25, of Aliquippa, who loved eye-catching cars and rap music, was one of the few friends who discouraged Eric's drug abuse. He was always up for anything, so when Eric asked whether he wanted to drive to Tarpon Springs, Ron said yes.

Their trip began with walks on the pier, drives on Dennis' Harley-Davidson motorcycles and bathing in the sun.

It ended on Oct. 22, when Ron was found dead in Eric's customized Honda Civic, a bullet hole in his side. He had borrowed the car that morning to drive to the beach. It was found along a bayfront street later that afternoon.

Eric was devastated. He blamed himself. That bullet, he believed, was fired by one of his drug connections and meant for him.

Ron's family blamed Eric, too. They thought he had something to do with the murder, though the police never arrested or charged him.

Eric wrote Ron's family a letter of apology. A short time later, he was sentenced on his drug charges: three months in county jail and nine months' probation. It looked like a death sentence at the time, but it would end up saving his life.

Meanwhile, Dennis was in a struggle for his own life. His liver had begun to deteriorate, and his esophagus to bleed from his years of drinking. In December 2001, he ended up in a Florida hospital. Doctors told him he was lucky to be alive.

He called Marcy, who had moved out of their Tarpon Springs home and into an apartment. The two had tired of the fighting and both filed for divorce, but she stayed with him all through the night. When Dennis was released a few days later, he made two decisions: If he wanted to live, he needed to quit drinking. And if he was going to die, he needed to be with his family.

Dennis boarded a plane bound for Pittsburgh.

We're orphans now

The man who returned from Florida was not the same Dennis that relatives in western Pennsylvania had known for the previous 10 years.

He had sworn off booze - for good this time - but the cirrhosis had taken its toll. Three-hundred-pound Dennis had wasted to about 185, and the swagger was gone from his step. The Dennis who got off the plane in Pittsburgh - the same man who had built tree houses for his children and booted footballs 80 yards - moved along the exit ramp in a wheelchair.

He was due in the night before, but missed his connecting flight in Atlanta. That triggered a series of frantic phone calls from his brother, Larry, to Georgia State Police, who finally found Dennis sleeping under an airport restaurant table. He had become disoriented from high ammonia levels in his body, a symptom of his liver disease.

He lived with his parents during his first months back and seemed to improve under his mother's care. He was taking his medication, going to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, and despite several hospital stays, he seemed to be back to his old self.

His close call in the Florida hospital had shaken him. Dennis, who had courted death over the past nine years, wanted to live again.

He teased Pete and begged her to make his favorite dinner of liver and onions. "Run a rake through that hair!" he would jokingly bellow to Pete. On shopping trips, he always bought little trinkets and toys for her beloved 100-pound boxer, Max.

After one of the hospital stays, Dennis developed a staph infection in his elbow that required intravenous medication. That was too much for his mother. Dennis moved in with his sister, Debbie, who worked for years in a doctor's office and could handle the IVs.

Caring for Dennis took much of Debbie's time. She administered his medicine (he often forgot to take it himself) and drove him to doctors' visits, his AA meetings and to the Cleveland Clinic, which had placed him on a liver transplant list.

On those two-hour drives to Cleveland, Dennis would blast music over the car stereo, dancing along in his seat.

At home, Dennis lived on the Internet, and Debbie would come home to find questionable Web sites popping up on the computer. A woman in a bikini still pops up every time Debbie signs on, but she refuses to delete it because it reminds her of her big brother.

He also exchanged e-mail with Marcy, who was still living in her apartment in Florida. Deep down, Dennis loved Marcy and hoped to reconcile, but the messages that Debbie would sometimes find were often abusive on both sides.

When Dennis first moved in, Debbie hid all the alcohol in her house and refused to take him to restaurants that served it, but she began to have confidence that this time Dennis was heeding his doctor's warning: One more drink would kill him.

Sober for the first time in years, Dennis realized what he had done to his children, and he was ashamed. Eric was in a Florida jail, and Leah was addicted to drugs. Dennis blamed himself.

The sober Dennis regained his faith in God. He started going to church and joked with Eric during visits and in phone calls that all his praying had restored his balding scalp and transformed gray hairs to brown. And he began wearing his wedding ring again, the one that Karen had slipped onto his finger so many years before.

Dennis was feeling better and decided to move out on his own. He leased an Oakdale town house in August 2003 and let Leah, who was out of money and places to stay, move in. But time was running out and so was the money. He had begun mortgaging his properties for cash.

Dennis spent his last months making amends. He visited old friends and bragged about Eric, then in a Florida rehab. His son was a good kid, he would say, and finally on the right track.

Dennis visited Karen's mother, Mary Waldron, in Crescent Township and had a fit when he found out that her television received only one channel. He showed up one day after that with a new TV and a recliner chair for her to sit in while watching it.

During one of the visits, he made Waldron promise that if he died, she would make sure he was buried in the same grave as Karen. Waldron agreed.

And he visited the old house on Walnut Street.

Dennis started remodeling the place before Karen died, and he finished after he got the settlement from USAir. Now he wanted to revisit his handiwork and his memories.

Its owners, Delores and Glenn Chimile, barely recognized him.

Dennis walked through the house from basement to bedroom, pausing in every room for a few seconds to look around. He seemed to sense it was for the last time.

He wrote letters to Marcy and Eric, apologizing for his past lifestyle.

He told Marcy that he always cared for her, no matter how he acted when they were together.

He wrote Eric that God had given him a second chance, and it was time for the family to pull together "after nine years of trying to kill ourselves." He asked Eric to forgive him for being such a lousy father and accepted all blame for Eric and Leah's drug problems. He urged Eric to always remember Karen.

"She was the best human being I've ever met," he wrote.

At the end of 2003, against his doctor's advice, Dennis flew again to Florida to see Eric. While he was there, he called Marcy to talk about their divorce settlement, and she agreed to meet with him. When he arrived, the police were waiting for him, Dennis' family said. Marcy had invoked a protection-from-abuse order that she had filed against him more than a year earlier.

Dennis spent several days in jail without his medication and then flew home. Three days later, he began complaining that he couldn't breathe. The old staph infection had resurfaced in his lungs. They were filling with fluid.

Debbie took him to Pittsburgh's Mercy Hospital. He was sick, but still the character. While there, he overheard a woman questioning a nurse about her father in surgery. The daughter complained that the hospital couldn't tell her anything about his condition.

"Get used to it!" Dennis yelled through a curtain that separated them.

"We don't even know where he is," the daughter told the nurse.

"Neither do THEY!" Dennis shouted.

Dennis insisted on leaving after that, and Debbie drove him home. The next day, his condition was worse. This time, they went to Allegheny General Hospital.

Dennis had a favorite pair of slippers that looked like two hairy gorillas. In the hospital waiting room, he realized he had forgotten them in the car and refused to see a doctor without the slippers. Debbie got them.

Two days later, he was jaundiced, emaciated and his breathing was shallow. The doctors wanted to put him on a ventilator. Before they did, he talked to Eric by phone.

"Hey, buddy," he said. "I don't think I'm going to make it this time."

It was his last conversation.

For a week or so, he was able to communicate to his family by squeezing their fingers. Then he lapsed into a coma.

Leah visited him daily, often with her good friend Dave Krestal, and bawled all the way to the hospital. Dennis had given her specific instructions about life support: "Pull the plug," he said.

On Jan. 15, the family honored his wishes. Dennis died peacefully about 45 minutes later.

Eric, who was still serving his probation in Florida, had received special permission from a judge to be at Dennis' bedside when he died. But Dennis' family gave doctors approval to disconnect life support while Eric was still on a flight home.

Dennis' old friend Stubby Burgunder was there, along with Dennis' brothers and sisters and Leah. They were devastated, but drew comfort from the fact that Dennis was finally at peace. Finally, he was with Karen.

At the funeral, Paul Dickson Sr. refused to speak to his grandchildren, and Pete blamed Leah for her dad's death. Marcy was not permitted to attend the funeral, and her name was omitted from Dennis' obituary, but Eric sneaked her in between viewings. Mary Waldron greeted her with a big hug and condolences. She never minded Marcy.

Dennis was buried in a favorite leather Steelers jacket. In the casket was his favorite T-shirt with "Chicks Dig Me" written across the front. Leah and Eric had intended to bury their father with the wedding ring that their mother had given him, but it had disappeared. Leah thinks one of her former drug-using friends stole it from her jewelry box.

It was the coldest day of the year, and ice was so thick in the cemetery that the cars were skidding on the road. Dennis hated the cold, winter being one of the reasons he moved to Florida, and Debbie could almost hear him saying, "This weather sucks!"

He was buried on top of Karen.

Afterward, Eric and Leah hugged their Grandma Waldron.

"We're orphans now, Grandma," they said.

"I've been an orphan for a long time," she replied. "We'll just stick together."

Picking up the pieces

Ten years after the crash and six months after their father's death, Leah and Eric are trying to pick up the pieces of their fractured lives.

As Dennis Dickson wrote in the weeks before he died: "Now it's time to do what God put us here to do, respect life, respect people, respect each other and thank God for the second chance."

They are adults now, and it's time to move on. They're trying.

When he was home for his father's funeral, Eric relapsed with drugs, a violation of his Florida probation. Authorities sent him back to jail for several more months. He returned to Pennsylvania in May. He is clean now and living with his Aunt Terri, who reminds Eric of his dad, and her housemate, Mary West.

For the first time in 10 years, he has rules and responsibilities. He has to mow the lawn and be home by curfew. He's not allowed to take phone calls during dinner, not even from his sister.

So far, he's happily obeyed. He seems to like the rules.

Over the summer he worked two jobs - one at a gas station, the other at an industrial park - and this fall, he is taking classes at the Community College of Beaver County, driving his new cherry-red pickup to campus.

He thinks he wants to be a teacher or a counselor.

Leah, who has "Mom" and "Dad" tattooed on her left leg with their birth and death dates, moved out of her grandmother Waldron's old house and into a town house in the Robinson Township area in July.

To pay the rent, she had to break her trust. The lump sum she received will cut down on her monthly payments when she turns 30, but Leah said she will still have enough for the future.

What that future holds, she's not sure.

She is in outpatient drug rehab and says she is trying to turn her life around. She still visits Grandma once a week and drives her to the store when she needs to pick up a carton of milk or a loaf of bread. She hopes to soon get a job, maybe something in an office. Her mother used to take Leah to work in her office, and she always liked that.

Family members have warned Eric to keep away from Leah and her world of drug addiction, lest he be pulled back in.

He knows he should heed their warnings, but sometimes he just needs his sister. He calls her his world. She says she would die for him.

They are bits and pieces of their parents. Eric has the diplomacy of Karen and her straight white teeth. He cloaks his words in soft cotton and laughs easily.

Leah is polarizing like Dennis and shares his jutting square chin. She speaks quickly, firing her words like a nail gun, with a biting wit.

But they are more cynical than their parents, having grown up with tragedy and under the judgmental eyes of outsiders. Leah and Eric know what people say about them: They had it made with the money, and they blew it.

It's true, their Uncle David says, but still somehow unfair.

"Everyone has an opinion on what they should have done after she died, but we haven't been in Dennis' shoes, or Eric's shoes or Leah's shoes," he says. "Dennis always said that he would give every nickel of that money back to have Karen back."

But he couldn't, and it's all gone now. Dennis left a legacy of debt. The house in Economy is up for sheriff's sale; the house in Florida recently sold. Dennis' estate owes money on Grandma Waldron's house and the beer distributor, and David imagines they will have to be sold to pay off Marcy, now a department store manager, who has filed for her third.

Most of the family treasures that Leah and Eric would have inherited from their parents are also gone.

Leah has her mother's china, Eric a velvet pouch with her jewelry and cracked credit cards and tattered pictures found at the crash site. The rest has been locked up in a storage unit, and their Uncle David will not give them access. Leah said David is angry with her behavior, but they have become accustomed to the disapproval of the Dicksons.

Dennis' parents hold the kids responsible for their father's death; his brothers and sisters pin most of the guilt on Dennis.

If Dennis would have died on that plane, "Karen would have held it together," Terri said.

But Leah and Eric don't blame their dad for what they have become. They don't blame him for the way that he died or the mess he left behind. Despite his problems, they know he loved them dearly, probably too much.

"Rules would have helped us, but he was a good dad. I don't care what anyone says," Leah said. "He was there when we needed him."

And they feel Karen has always been there, too, a guiding spirit to help them overcome the turbulence in their lives. They believe she kept Dennis on earth long enough to know they would be OK.

And they truly believe they will be.

Some days will still be hard. They will still envy people who have parents. Eric will still wish Karen could see him graduate from college. Leah will still wish Dennis could walk her down the aisle at her wedding. They will both wish their children could have grandparents.

"It's tough," Eric said. "I love my aunts, but sometimes I …"

He pauses and tucks his chin into his chest.

"… want to talk to Mom and Dad," Leah said. "I know."

JUNE 19, 1953

Dennis Dickson is born.

OCT. 28, 1953

Karen Waldron is born.

1970

Karen and Dennis begin dating during their junior year at Moon Area High School.

1974

Karen graduates from Sewickley Valley Hospital School of Nursing, winning the "Outstanding Nurse" award, then enrolls at the University of Miami to pursue a bachelor's degree in nursing.

AUG. 21, 1976

Karen and Dennis are married at St. Catherine Catholic Church in Crescent Township.

MAY 4, 1978

Karen and Dennis buy a house on Walnut Street in Crescent Township.

APRIL 15, 1980

Leah Katherine Dickson is born.

APRIL 24, 1984

Eric Jon Dickson is born.

MAY 12, 1986

Karen and Dennis buy a house on Ridge Avenue in Crescent Township for Karen's parents.

MAY 1994

Karen graduates from Carnegie Mellon University's H. John Heinz School of Public Policy and Management, with a master's degree in public management.

SEPT. 8, 1994

Karen dies with 131 others when USAir Flight 427 crashes in Hopewell Township. She is returning from a business trip to Chicago.

SEPT. 9, 1994

Federal investigators launch what will become the longest airplane crash investigation in U.S. history.

SEPT. 13, 1994

Rumors circulate citing a bomb, a fire, reversing engines, birds and turbulence as possible crash causes, but investigators find no tell-tale clues among the wreckage.

SEPT. 16, 1994

More than a week after the crash, recovery workers continue to remove human remains from the crash site.

SEPT. 28, 1994

Funeral services for Karen are held after her left hand and forearm are identified. Her remains are buried in St. James Cemetery, Sewickley Heights.

NOV. 4, 1994

Dennis files suit against USAir.

JAN. 23, 1995

The National Transportation Safety Board begins a week of public hearings into the crash but offers no definitive cause. Investigators focus on a malfunctioning rudder, pilot error and possible turbulence from another jet.

SEPT. 8, 1995

One year after the crash, investigators are no closer to announcing the cause.

OCT. 25, 1995

Dennis settles his suit with USAir for about $2.1 million, plus $300,000 each for Leah and Eric.

NOV. 17, 1995

Tests rule out turbulence as the cause of the crash.

MARCH 1, 1996

Crash investigators determine that a sudden large movement of Flight 427's rudder caused the airplane to veer left, roll over and plunge to earth. They are not sure what caused the rudder malfunction.

SEPT. 8, 1996

A second anniversary passes with still no definitive word on the cause.

MAY 25, 1998

Dennis marries Marcy Cuervo of Moon Township.

MARCH 10, 1999

Dennis and Marcy buy a house on Green Forest Drive, Economy, for about $240,000 and move there.

MARCH 25, 1999

The NTSB rules that a hydraulic valve on Flight 427 jammed, causing the rudder to radically deflect and the plane to crash.

DECEMBER 2000

Dennis and Marcy move to Tarpon Springs, Fla., after buying a bayfront house there.

DECEMBER 2001

Dennis, suffering from cirrhosis of the liver, moves back to Pennsylvania to live first with his parents then with his sister. He and Marcy have both filed for divorce.

SUMMER 2002

Eric is arrested twice for cocaine possession and drunken driving. Later that year, he becomes a suspect in the murder of a friend but is never charged.

EARLY 2003

Eric serves three months in a Florida jail on drunken-driving and drug charges.

JAN. 15, 2004

A Florida judge allows Eric, who is on probation, to return to Pennsylvania to be with his dying father. Dennis dies before Eric can arrive.

MAY 2004

After serving another several months in jail for violating his probation, Eric is released and returns to Pennsylvania to live with an aunt.

This article originally appeared on Beaver County Times: Ten years later: A family destroyed