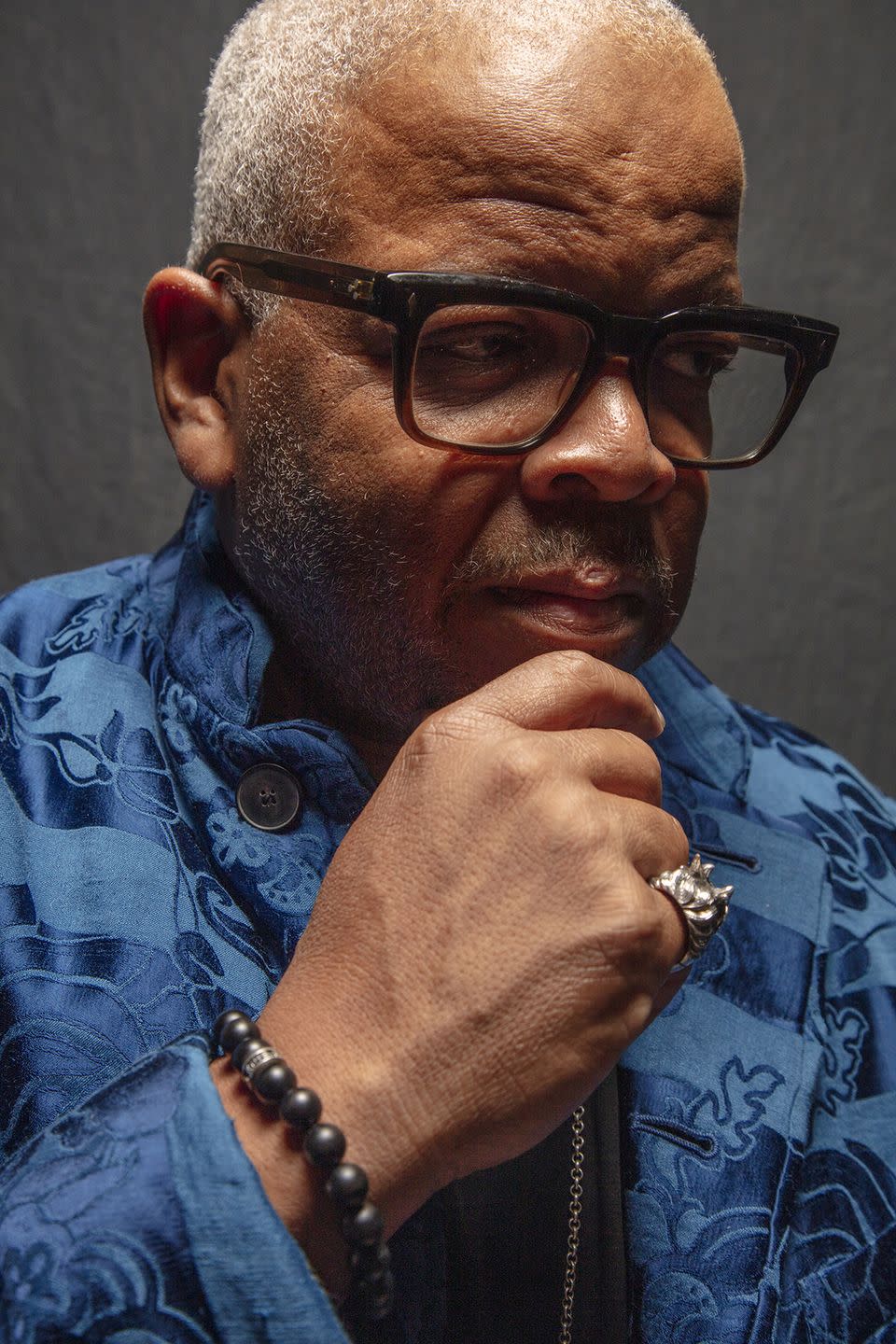

Terence Blanchard Can't Escape the Opera

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

When Fire Shut Up in My Bones opened the current season at New York City’s Metropolitan Opera on September 27, it was the first performance at the Lincoln Center opera house in nearly 18 months—and the first-ever production there by a Black composer.

On October 23, Fire, which was composed by Grammy winner and Oscar nominee Terence Blanchard (with a libretto by writer, director, and actress Kasi Lemmons) and based on the memoir by Charles Blow, will make its final performance at the Met and will be screened live in movie theaters around the world. It promises to be a grand finale for an opera the New York Times called “a fresh, affecting work.” The next stop for Fire will be Chicago's Lyric Opera in 2022.

Here, Blanchard—who also recently released a new album, Absence, and will be touring the United States throughout November—talks to T&C about creating Fire, finding comfort in opera, and why he’s become wary of opening nights.

How did you begin adapting Charles Blow’s memoir into an opera? What made it feel like the right medium?

My manager, who’s also my wife, read Charles’s book and said, “I think this would be a good story.” She had me read it and agreed, and at the same time she sent it to Jim Robinson at the Opera Theatre of St. Louis. We all decided to call Charles and once we agreed, we brought him to St. Louis to meet Kasi, who we had hired to write the libretto; we knew if anyone could do it, it would be her, she’s brilliant and we’ve worked together on several films. There wasn’t a lot of going back and forth about should we or shouldn’t we.

So, it began in St Louis. It was my second opera for the Opera Theatre of St. Louis. They commissioned me for the second opera the night of the premiere of the first one; I’ve got to stop doing premieres because every time I do, I get another commitment. The Met commissioned me to write a third one the night of the premiere of this one. Can I at least take a nap first?

Fire is your second opera, but you might have previously been better known for jazz and film scores. What about the medium speaks to you?

You can tell very vivid stories in opera, but the first thing you must do is get over the notion of writing an opera. That word carries a lot of history with it and can be daunting or overwhelming if you let it. My composition teacher told me, “Don’t write opera, tell a story.” It’s the same thing with jazz and people who aren’t fans, they generalize about it. And that’s true for people and opera as well. I do it too; I had generalizations in terms of my expectations about what the music should be, but like jazz, it can be whatever it wants. You just need to be confident enough in your skills to tell a story in a clear, concise fashion.

Do you feel differently about working in different mediums?

It’s all part of the same expression of what I love, but the different genres do stretch different muscles. With jazz, I have more of an opportunity to create on the fly. In opera, there’s room, but not as much, because there’s dialogue that must be delivered to help tell a story. With film, I’m not helping with dialogue at all, I’m supporting it more than anything. There are slight differences in terms of the intent behind the music, but stylistically it all comes from the same place.

How did Fire change between St. Louis and New York?

When Kasi originally wrote the libretto, she wrote it like a film, where the scenes could go back and forth rapidly, and we had to structure some of that differently to make it flow for the theater. For this performance, we fine-tuned a few things and added an aria, there were also little lines that were spoken before that were sung this time. We also added an overture at the beginning. The way things started in St. Louis is that the Charles character would run on stage, out of breath, and suddenly, the music would start. We couldn’t do that at the Met—he’d have to be Superman to run down that aisle and jump onto stage. So, we decided to have an overture to open it up.

This production is the Met’s first in almost two years, and its first ever by a Black composer. Are those things that add weight to your job?

I wasn’t feeling any of that, because being the first Black composer here is an honor with an asterisk. I know I’m not the first one to be qualified. As a matter of fact, some of the guys at the Met pulled out a ledger that shows William Grant Still had submitted three operas and had them rejected by the Met. The comments that were made in the book called him amateurish and a dilletante who didn’t deserve to have his music presented. My focus was on honoring people like him, not wanting to let any of those souls down after their efforts. I’m standing on some strong shoulders, so I focused on making rehearsal the best it could be. I didn’t know what the response was going to be, it could have been awful, so we just worked as hard as we could. But I wouldn’t call it pressure; it was a joy to go to rehearsal every day. And by now, most of my work is done—I’m going to see a free concert almost every day.

Until you start on that next one, right?

Really, you had to remind me of that?

You Might Also Like