The Term 'Drought' Is Out of Date for the American Southwest. They Call It 'Aridification' Now.

On Wednesday, representatives of the Colorado River Water Users Association, a consortium of seven western states, as well as representatives of the federal government, opened a meeting in Las Vegas. Nearly 20 years of drought conditions combined with increased usage in those states have shrunk reservoirs and generally depleted the water supply to the point where drastic-and, very likely, painful-collective action has become immediate and vital.

When the meeting was first called, its purpose was to develop a plan for that action, and a method by which the states that depend on the Colorado River and associated water could share the sacrifice that everyone agreed was necessary and imminent. That, alas, didn't happen. From the Wyoming News:

Arizona has been the holdout, with farmers, cities, Indian tribes and lawmakers in the state set to be first to feel the pinch still negotiating how to deal with water cutbacks when a shortage is declared, probably in 2020."There will be cuts. We all know the clock is ticking. That's what a lot of the difficult negotiations have been around," said Kim Mitchell, Western Resource Advocates water policy adviser and a delegate to ongoing meetings involving the Arizona Department of Water Resources, Central Arizona Project, agricultural, industrial and business interests, the governor, state lawmakers and cities including Tucson and Phoenix.

In Arizona, unlike other states, a final drought contingency plan must pass the state Legislature when it convenes in January. Federal water managers wanted a deal to sign at the annual Colorado River Water Users Association conference beginning Wednesday in Las Vegas, and threatened earlier this year to impose unspecified measures from Washington if a voluntary drought contingency plan wasn't reached.

The water associated with the Colorado River supports 40 million people and irrigates millions of acres of prime agricultural land, and, right now, today, all of that is in desperate shape, and there is no time remaining for dilatory measures.

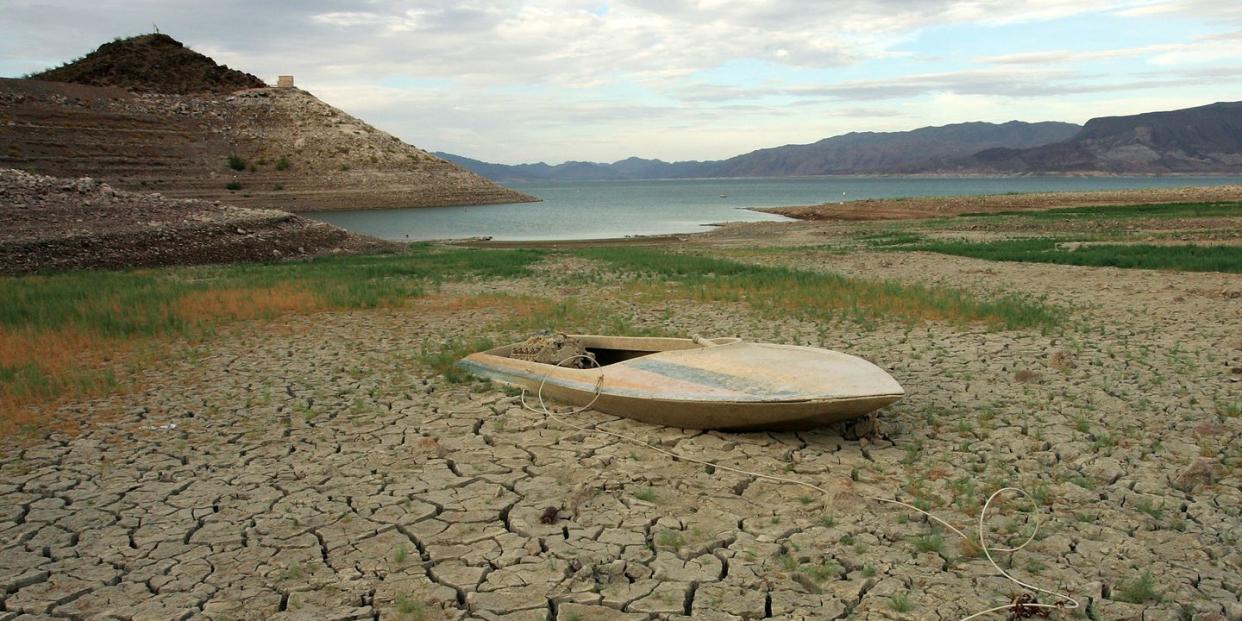

After 19 years of drought and increasing demand, federal water managers project a 52 percent chance that the river’s biggest reservoir, Lake Mead behind Hoover Dam, will fall low enough to trigger cutbacks under agreements governing the system. The seven states saw this coming years ago, and used Colorado River Water Users Association meetings in December 2007 to sign a 20-year “guidelines” plan to share the burden of a shortage. Contingency agreements would update that pact, running through 2026. They call for voluntarily using less to keep more water in the system’s two main reservoirs, lakes Powell and Mead.

In the course of looking at what's going on with the planet's water, I've learned a new word: "aridification." It was a word coined to describe what's going on with the area served by...wait for it...the Colorado River. From the High Country News:

This spring, the Colorado River Research Group, an independent team of scientists focused on the river, labeled the climate transition in the Colorado River Basin “aridification,” meaning a transformation to a drier environment. The call for a move away from the word “drought” highlighted the importance of the specific language used to describe what’s going on in the Southwest: It could shift cultural norms around water use and help people internalize the need to rip out lawns, stop washing cars and refrain from building new diversions on already strapped rivers.

Essentially, it means that dry places are getting drier, and that the transformation is likely to be permanent, unless human beings radically alter their behavior toward water usage. From the Colorado River Research Group:

Perhaps more importantly, moving forward means abandoning the mindset that current changes to climatic and hydrologic regimes are a temporary phenomenon. We are not likely to ever return to normal conditions; that opportunity has passed (Milly et al, 2008). Rather, there are two possible new normals.

First is a continuation (and likely acceleration) of the current drying trend and the accompanying increase in variability, an outcome largely “baked into” the system by existing atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations.

A second, and better, new normal would be to establish regional hydrologic conditions at a steady new level-a step change-that results from the stabilization of atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations at some new equilibrium. Achieving this second outcome will require many actions taken across the globe, and in sectors beyond water management. Nonetheless, the Colorado River management community can still be a leader in promoting and contributing to such actions.

There is much to gain in the basin by leading on these larger issues, as well as by exploring local opportunities-such as dust suppression-to slow or halt ongoing environmental changes. It is time for water managers to both adapt for the profound changes the future holds and to advocate within the political sphere for a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. A very modest starting point is to admit words such as drought and normal no longer serve us well, as we are no longer in a waiting game; we are now in a period that demands continued, decisive action on many fronts.

This has been your now-almost-daily Water Apocalypse update.

Respond to this post on the Esquire Politics Facebook page here.

('You Might Also Like',)