In a terrorism ignorant world, Spitz's Munich 1972 showing overshadowed

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor's note: Bob Hammel covered the 1972 Munich Olympics for the Bloomington Herald-Telephone, by far the smallest U.S. newspaper to have a credentialed reporter there. This is the second of two parts.

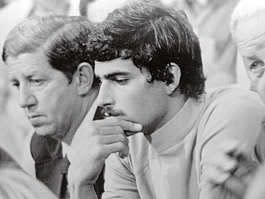

MUNICH — Olympic swimming officials set up a special mass interview for early morning the day after Mark Spitz finished his competition. It was at 8 a.m., on a Tuesday in an open room set up for maybe 300. About 1,000 journalists showed up.

And it was at that gathering most in the room, including me, heard for the first time what had happened overnight and was going on at the moment not far from where we were — maybe two city blocks. An Olympic official, not casually but a long way from sensationally, announced that an unidentified invading unit had come over the Olympic Village fences during the night and was in command of Building 31, where the Israeli athletes were housed. At least one Israeli was known to be dead, killed at the building entrance when the invaders stormed in. That brief announcement was the first that almost any reporter in the Village there knew about it, anyone outside ABC-TV, which already was telling America.

It was such a different, terrorism-ignorant world then. Inside Olympic Village, the Spitz interview went on. Amazingly, incomprehensibly now — so did competition.

Spitz had a better grasp of what all this could mean than the people running the Olympics. Raiders taking the Israeli building made their anti-Jew intent unmistakable. Spitz was, at the moment, the most famous Jew in the world, his face on every news magazine cover, leading off every TV newscast. Could anyone be a more inviting “prize” for armed Jew-haters?

The Mark Spitz-tells-all conference, where Spitz answers every question and flashes that handsome smile, didn’t happen. Security people stood in front of him, his face poked through cracks in their phalanx, and he woodenly answered a couple of questions. It was obvious this was going nowhere. The conference quickly ended.

Competition went on in all sports, on schedule, in venues all around the Village. I swear — though I have since scanned two officially published books of results and found no confirmation — that once I had a sheet of paper from the blizzard of fresh print-outs that each journalist received every morning, a sheet that listed the Tuesday morning competition results and showed in one event the name of an Israeli athlete and said: “Disqualified — DNA.” Did not appear.

It wasn't until noon did someone in Games officialdom decided they really ought to stop competitions, for a while.

One can only wonder what thoughts went on in the minds of captured Israeli athletes throughout the day Tuesday when they looked out their window and saw a blithe world playing games.

With 10 human beings in the hands of trapped maniacs, their colleagues boxed and raced kayaks and played volleyball. Others sun-bathed and went for strolls and even enjoyed convivial banter on the very lawn outside Building 31.

Seven events. Seven golds. Seven records. 50 years ago, IU's Mark Spitz became an icon.

I was one of the American journalists who sat that afternoon on the floor of the Associated Press office and watched a TV monitor. ABC had cameras everywhere, showing everything: Building 31, and the floor where the hostages were being held, because every now and then a head of one of the captors peered out to look around. On a balcony outside one of those upper floors, a man wearing a full facial mask and carrying an automatic weapon occasionally walked around brazenly, scanning for possible threats, or the escape vehicle they had demanded.

An afternoon deadline was set: If the invaders were not provided with a safe escape by 5 p.m., they would kill one of the hostages. That time passed; then another deadline at 6, another at 7. Peter Jennings, 30-ish, was ABC News’ man in charge. Rushed to the scene to take news-reporting command, he said in words I've never forgotten: “That is the Arab mentality.” They'll never carry out a threat, Jennings was saying. The implication: Wait them out. Keep them sweating. They won’t do anything.

Jennings was the first to say the words “Black September” on the air. In a Sports Illustrated interview 25 years later, the raid’s chief architect said the deadlines were phony all along, designed to build tension around the world — back home in America, for example, where 5 p.m. was 11 a.m. in New York, then 6-was-noon, then 7-was-1 p.m. And both tension, and worldwide attention, did build.

I left the AP office in late-afternoon and — no wiser about terrorism than Jennings — walked to the closest point to Building 31 outside the high fence the terrorists had scaled. It was a wire fence, see-through. I wasn’t alone. People were all around, almost festive — nowhere else to go and nothing else to see, they seemed to be saying.

Spectators by the thousands, their evening entertainment tickets no good because 12 hours after an act of murder and kidnapping somebody of authority decided to stop playing for a while, spent their idle time like picnickers in a park. They perched on the hillsides looking into Building 31, in such numbers they must have looked like a colorful wave of Alpine flowers to those frightened eyes inside the building … eyes that knew the waving color out there wasn’t floral at all but clothing for human bodies with eyes that looked back at them and their plight as a dull evening's saving entertainment.

Night came. In the dark we all left, went to bed, and heard during the night the hostages had been released safely.

It was an optimistic, premature public relations-conscious announcement that turned out to be a lie. An hour or so later, on ABC in the middle of the evening back home but about 3 a.m. in Munich, exhausted and distraught Jim McKay said:

“They’re all gone.”

All nine captive Israelis, and seven Palestinians became the human carnage from a Keystone Cops ambush police laid at the darkened Munich airport where all had been bused for an ostensible “safe” flight out.

We trouped that late-morning to a hastily scheduled memorial service in the same stadium where the Opening Ceremonies, just nine days before, had been so sacrosanct, so peaceful.

The morning quiet was penetrated for mournful Beethoven tributes, played by the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra … for words of memory, by Olympic Organizations Director Willie Daume of West Germany, German President Gustav Heinemann, International Olympic Committee President Avery Brundage of the U.S., and Israeli's Chief of Mission, Shmuel Lalkin.

“A truly despicable crime,” said President Heinemann … “A day of unspeakable sorrow,” said Daume … “Every civilized person recoils in horror,” said Brundage. Lalkin said: “Let the terror of the past hours finally awaken the consciences of the world.”

But Brundage pronounced stridently, “The games must go on,” and they will. And in the future, there will be Israeli teams there again, a solemn pledge Lalkin made of participation “in a spirit of brotherhood and fairness.”

“The Olympic ideal has not been contradicted,” Heinemann said. And indeed it hasn't, certainly not the idea that man should be able to gather and compete in a harmony of races and beliefs. It has worked better here, despite one horrifying aberration, than in the world outside Olympic Village.

Spitz was one of five IU swimmers at Munich who were billeted together in a four-room, second-floor apartment in the quarters assigned to the U.S. team, about a city block from the Israelis' building.

One of those five, sprinter John Murphy, said he knew nothing of it all until breakfast – while Spitz was at the press conference. Spitz returned to the apartment before Murphy, and it was obvious to Murphy that Olympic officials had realized Spitz’s particular peril.

“There were four guys from the Munich police there standing guard,” Murphy said. “One at the door, one inside and two in the room with Spitz … .”

Within minutes, they had Spitz out of the Village. By then, Murphy said, they had torn out the Spitz nametag on the door. “They didn't take any chances,” he said. “They cleaned out everything referring to Mark.”

They did finish those Games, among the items of post-disaster history (on the last Saturday night) the double do-over basketball victory by the Soviet Union over the United States, the most famous international basketball game ever – maybe the whole sport’s most famous game ever. Then, six nights after the raid, we were back in that stadium for the Closing Ceremonies.

It’s the Olympics the U.S. would prefer to forget – that section of the U.S. separated from direct association with Mark Spitz, who made the Games his personal passport to all-time sports fame.

Nothing in these Games, or likely any that came before or will come later, touches the scope of Spitz’s seven gold medals in swimming, the easy memory in a mental rerun of Munich happenings.

And nothing at these Games, or certainly before or hopefully after, approaches the sorrow of the mass murders perpetrated here, leaving 16 people dead. …

It's an Olympics that will be remembered for German efficiency and German misfortune at getting caught with its guard down in the very Olympics calculated to portray the country as newly non-military, a friendly sort of place. That face changed after bloody Tuesday, and the last five days no-nonsense guards patrolled … the entire Olympic area, many of them armed and some blatantly walking patrol with sub-machine guns in hand.

Above all, it was an Olympics of people’s achievements.

And people’s failures.

This article originally appeared on The Herald-Times: Bob Hammel covered 1972 Munich Olympics marred by terrorism