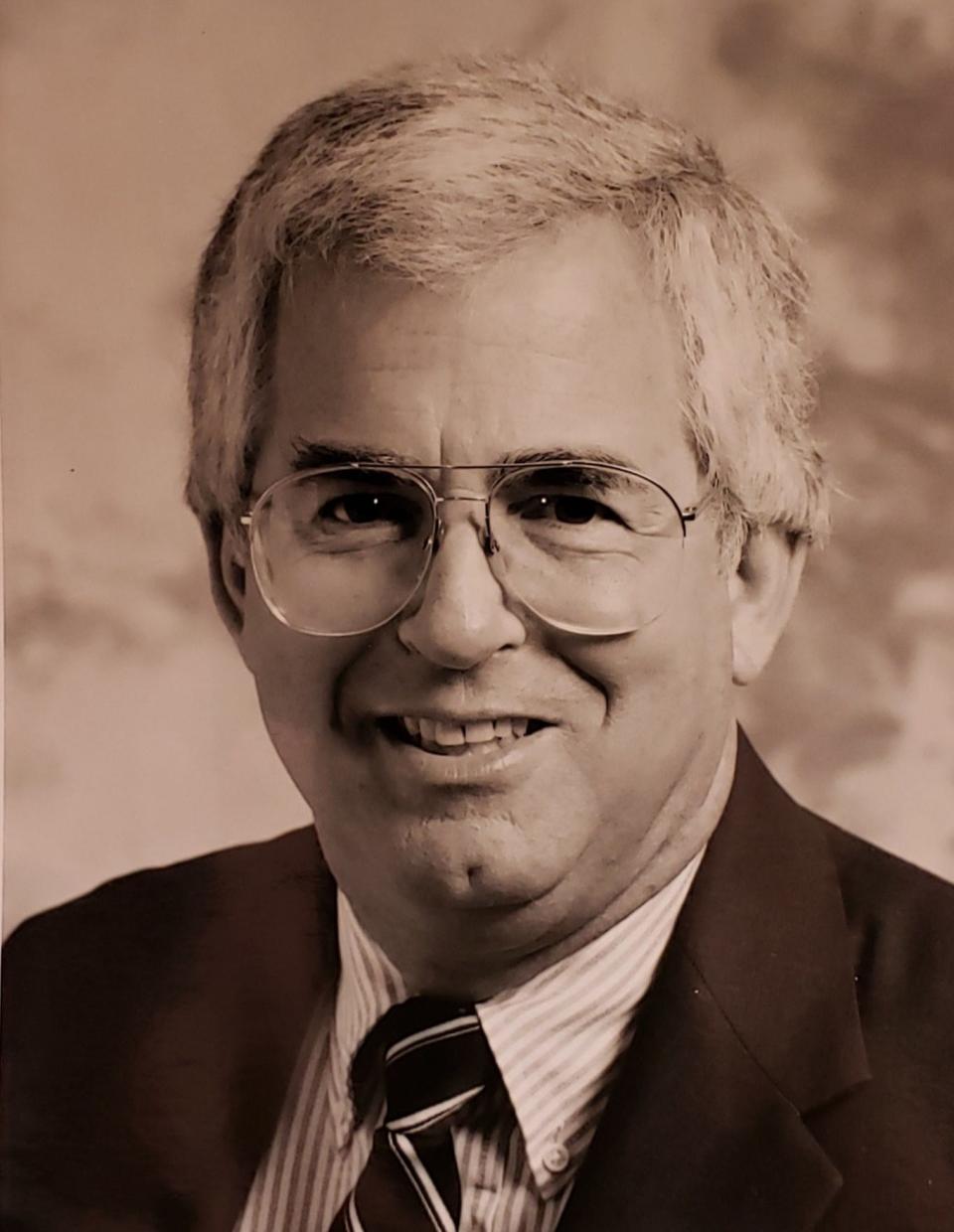

Who was Terry Kahn? The frugal Indiana multimillionaire who left everything to charity

Terry Kahn kept to himself. He had no close family and lived in a modest south-side Indianapolis home off Southport Road in the Holly Hills subdivision.

Notorious for being thrifty, Kahn knew where every penny was spent, loved his Costco membership and always split the check when he went out to eat with coworkers, acquaintances and friends.

No one could ever reach him by cellphone because the technology was just too pricy; someone on the street surely would have one he could borrow.

Kahn even deemed an obituary too frivolous of a purchase, which is why one was never written after he died on Jan. 31, 2021.

During his 78 years of life, that frugality allowed Kahn to stockpile $13 million. But what would become of all that money after his death?

"I don’t care. You decide. I’ll be dead,” he would repeatedly tell his executors in the years before he died.

The executors of Kahn's estate were surprised to be chosen.

In life, Kahn liked to have a captive audience and to achieve that, he would routinely insist on picking up his dining companions for meals that could last hours.

During one of those notorious meals, he asked Indianapolis lawyer Dwayne Isaacs, to put together a simple will and be a co-executor of his estate.

Isaacs met Kahn through the Health Foundation of Greater Indianapolis. Kahn was a founding board member and Isaacs was the foundation’s attorney. After Kahn left the board in 2010, the two became regular lunch companions, meeting up every month for a decade.

The other co-executor was Vance McLarren, a healthcare executive now based in Orlando. McLarren met Kahn while he was a fellow at Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center, where Kahn worked for almost 30 years as the chief of human resources. They went to many sporting events together. McLarren left Indianapolis in 2014 but returned a few times a year to visit family; Kahn asked to meet for lunch every time.

Both were a bit surprised Kahn tapped them to help with his estate, but they knew he had few confidantes — especially ones he would trust with such an ask.

“Terry knew that we would do the right thing when called upon," McLarren said.

One of the only other people involved in Kahn's life, whom Isaacs and McLarren did not meet until the end, was Alexa Helm. She worked as his human resources assistant for three and a half years before pursuing nursing school.

She told Indianapolis Monthly that she loved her job and he treated her well, but it took a special kind of person to work with Kahn.

"You had to have a little patience,” she said.

Helm and Kahn lost touch when she left her job, but reconnected many years later and she became another one of his dining companions.

She played a different role near the end of his life, setting up medical and hospice care for him.

"She was absolutely an angel through the last year and a half or so with us," Isaacs said.

Kahn 'could not let go of the money'

When Isaacs and McLarren agreed to be co-executors, Kahn told them he probably had $3 million to $4 million tucked away. They did not find out the actual total until a month before his death.

Before he got sick, the executors encouraged Kahn to provide input on where the money should go. With every suggestion they made, Kahn shot them down.

Children's Museum? Butler? No, they have enough funding.

His alma mater, the University of Southern California? Nope, he'd never give them money.

“We're like, ‘Well, Terry, kind of give us some ideas, man,” McLarren said. “No matter what idea that we had he'd always find some reason not to do it."

Why not just donate the money himself? He tried, with much encouragement from Isaacs and McLarren, but he struggled to hand it over.

In the few donations he made himself, he micromanaged how the money was spent, which was not ideal for the recipients.

“Terry just could not let go of the money,” McLarren said.

How would they decide?

Asking his executors to make those choices for him after his death was easier — for Kahn.

Isaacs and McLarren knew it was a huge undertaking, but also acknowledged the opportunity they had to make a difference in the community on Kahn's behalf.

They decided to divide and conquer to find smaller organizations they felt Kahn would have approved.

"I felt like it was a very large responsibility," Isaacs said. "I wanted to do the right thing."

Isaacs and McLarren did a lot of research. Two years of research. Checking organization tax filings to make sure they had the infrastructure to handle such a large donation and that the money would be put to use.

“I would... be pretty darn certain that was an organization that we wanted to contribute to before I made contact,” Isaacs said.

They ended up opting for a rolling process, calling about three organizations at a time, and getting the details ironed out at one before moving on to the next.

“The question would be 'what would you do with a million dollars if we gave you a million dollars?',” Isaacs said. “You don't need to tell me right now. Think about it. Talk to your board. Come back. Write a letter. It doesn’t have to be some formal grant proposal. Write a letter that includes a bunch of details you want and come back to me.”

Almost three years after his death, Isaacs and McLarren distributed the entirety of the $13 million to local organizations.

Kahn was a veteran who served in the Army for three years in Vietnam and had a long career working for VA Medical Centers across the country, so it made sense organizations that support veterans would receive a donation.

He was diagnosed with non-alcoholic cirrhosis of the liver, which ultimately led to his death. Kahn was also diagnosed with kidney cancer in 2018. They felt because of his health history, money should be donated for health care, support and education related to his conditions.

He loved sports. One of his only splurges was buying tickets to see the Colts, Pacers and Butler Bulldogs. While they knew he would not approve of any of his favorite teams receiving a donation, there were other ways to make an impact relating to sports like donating to the YMCA by his house.

Kahn cared about kids. That was the only hint he gave to his executors about where some of his money could go.

After making his first donation, Isaacs was in his car when he had a realization.

"Terry had given me an incredible gift," Isaacs said. "The ability to give away $13 million... I mean what a gift."

In the end, Teachers Treasures, Baxter YMCA, Washington Township Schools Foundation, Advent Health Foundation, Pathway to Recovery, Little Red Door, Indiana University Foundation, HVAF of Indiana, Coburn Place, the Boys & Girls Club and Folds of Honor all received a donation.

Each organization was able to put Kahn's money to good use.

Baxter YMCA was able to pay for two artificial turf soccer parks and a 40-yard open turf field that will be of multiple uses to the YMCA and their summer programs.

The Indiana University Foundation established the Terrence P. Kahn Liver Disease Program of Excellence Fund and a Professorship of Nephrology in Kahn’s name.

The donation made to Teacher’s Treasures was nearly double their typical annual budget.

Isaacs and McLarren are content with Terry Kahn’s legacy and they think he would be pleased, too. His generosity will be remembered in the Indianapolis community for years to come.

“Despite being surprised and the work that was involved in it, I look back — I'm glad I said yes to Terry when he asked, and to be a part of that is kind of special,” McLarren said.

Katie Wiseman is a trending and breaking news intern at IndyStar. Contact her at klwiseman@gannett.com. Follow her on Twitter @itskatiewiseman.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Indiana man known for frugality left $13M to charities after death