Terry stops gone wrong? New York’s stop-and-frisk decision

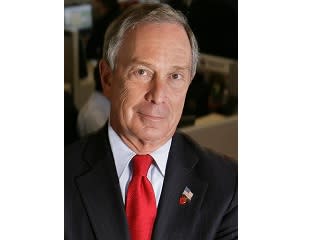

New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg says a federal judge who ruled his city misused the power to search people on the street in a “Terry stop” doesn’t understand the Constitution.

Judge Shira A. Sheindlin, in a potential landmark decision on Monday, basically said the same thing about Bloomberg’s stop-and-frisk policies in New York City.

So what are the basics of the case and what’s a Terry stop?

In 1968, a landmark Supreme Court ruling called Terry v. Ohio dealt with what Chief Justice Earl Warren said were “serious questions concerning the role of the Fourth Amendment in the confrontation on the street between the citizen and the policeman investigating suspicious circumstances.”

The rule defined by the court, subsequently known as a Terry stop, is that “in justifying the particular intrusion, the police officer must be able to point to specific and articulable facts which, taken together with rational inferences from those facts, reasonably warrant that intrusion.”

“Our evaluation of the proper balance that has to be struck in this type of case leads us to conclude that there must be a narrowly drawn authority to permit a reasonable search for weapons for the protection of the police officer, where he has reason to believe that he is dealing with an armed and dangerous individual, regardless of whether he has probable cause to arrest the individual for a crime. The officer need not be absolutely certain that the individual is armed; the issue is whether a reasonably prudent man, in the circumstances, would be warranted in the belief that his safety or that of others was in danger,” said Warren.

Bloomberg has cited his city’s stop-and-frisk policy as the basis for the city’s drop in murder and other major crime rates in the past decade. Police officers have saved the lives of thousands of young black and Hispanic men by taking guns from them under the policy, he contends, conducting what the city said were legal Terry stops.

But Judge Sheindlin of the Federal District Court for the Southern District in New York City found consistent and serious violations of citizens’ Fourth Amendment rights to be free of unreasonable searches and seizures during police stops and frisks.

Sheindlin found the New York City Police Department was liable for a pattern and practice of racial profiling and unconstitutional stop-and-frisks in a historic ruling. She appointed Peter L. Zimroth, a former corporation counsel and prosecutor in the Manhattan District Attorney’s office, to monitor the Police Department’s compliance with the Constitution.

Judge Sheindlin wrote in her opinion “that this case is not about the effectiveness of stop and frisk in deterring or combating crime. This Court’s mandate is solely to judge the constitutionality of police behavior, not its effectiveness as a law enforcement tool. Many police practices may be useful for fighting crime — preventive detention or coerced confessions, for example — but because they are unconstitutional they cannot be used, no matter how effective.”

For much of the last decade, Judge Sheindlin found, patrol officers had performed Terry Stops of innocent people in New York City without any objective reason to suspect them of wrongdoing.

“I also conclude that the city’s highest officials have turned a blind eye to the evidence that officers are conducting stops in a racially discriminatory manner,” Sheindlin said as she cited statements that Bloomberg and the police commissioner, Raymond W. Kelly, have made in defending the policy.

The decision rests on a large body of statistical evidence about police paperwork between 2004 and the middle of 2012 about 4.43 million Terry stops, when the average number of stops each year rose from 314,000 in 2004 to 686,000 in 2011.

Frisks for weapons followed in about half the stops, with police finding weapons only 1.5 percent of the time. Six percent of the stops resulted in arrests and summons.

A total of about 83 percent involved blacks (52 percent) and Hispanics (31 percent), though those groups make up 52 percent of city residents (23 percent black and 29 percent Hispanic).

The city justified the discrepancy on the grounds that a higher percentage of city crimes are committed by young minority men.

“This might be a valid comparison if the people stopped were criminals,” Sheindlin wrote, but “nearly 90 percent of the people stopped are released without the officer finding any basis for a summons or arrest.”

And blacks and Hispanics “were more likely to be subjected to the use of force than whites, despite the fact that whites are more likely to be found with weapons or contraband.” The judge wrote, “between 2004 and 2009, the percentage of stops where the officer failed to state a specific suspected crime rose from 1 percent to 36 percent.”

After Sheindlin’s ruling was announced, Mayor Bloomberg told reporters the policy was a key factor in reducing New York’s murder rate.

Link: Read Press Conference Transcript

“There is just no question that stop-question-frisk has saved countless lives. And we know that most of the lives saved, based on the statistics, have been black and Hispanic young men,” Bloomberg said.

Bloomberg also didn’t agree with Sheindlin’s legal reasoning.

“This is a dangerous decision made by a judge who I think does not understand how policing works and what is compliant with the U.S. Constitution as determined by the Supreme Court,” Bloomberg said.

He also confirmed the city will appeal the judge’s ruling and gave some hints about the appeal.

“Throughout the case, we didn’t believe that we were getting a fair trial. This decision confirms that suspicion, and we will be presenting evidence of that unfairness to the Appeals Court,” Bloomberg said. “We will also be pointing out to the Appeals Court that Supreme Court precedents were largely ignored in this decision. The NYPD’s ability to stop and question suspects that officers have reason to believe have committed crimes, or are about to commit crimes, is the kind of policing that courts across the nation have found, for decades, to be constitutionally valid.”

“If this decision were to stand, it would turn those precedents on their head – and make our city, and in fact the whole country, a more dangerous place,” he said.

Recent Constitution Daily Stories

Judge explains why New York’s stop-and-frisk policy is unconstitutional

How NSA surveillance endangers the Fourth Amendment