Texas Was Already One of the Hardest States to Vote in. It May Get Even Harder

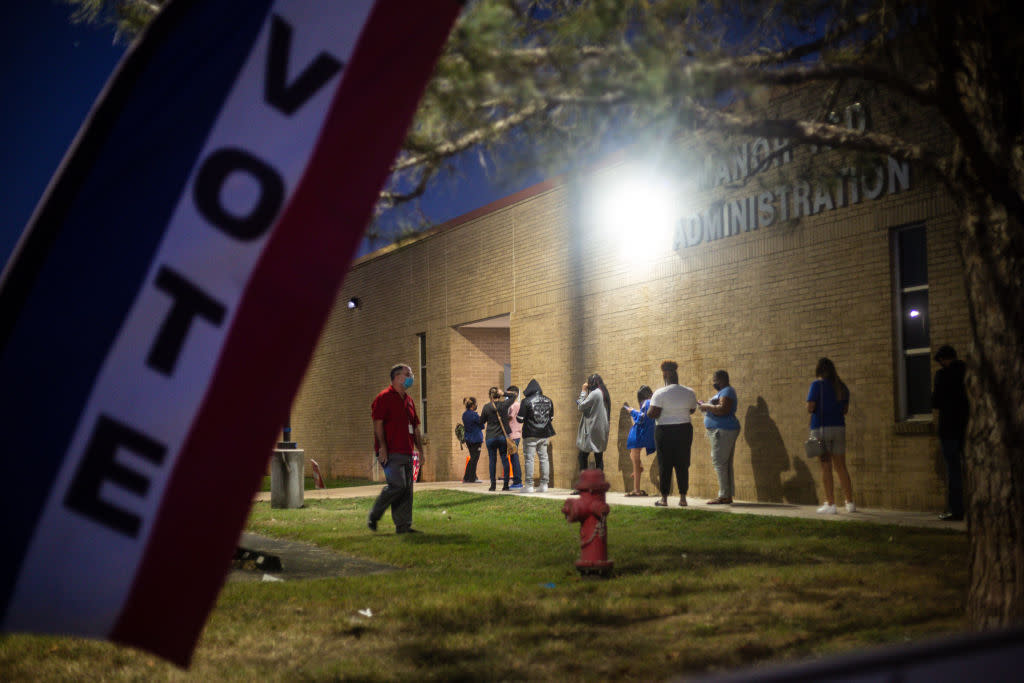

With an hour left to vote, people wait in line at Manor ISD Administration building in Manor, Texas, on November 3, 2020 Credit - Montinique Monroe—Getty Images

The Texas House of Representatives approved a spate of new voting restrictions Friday in a state that has long been considered one of the hardest to vote in in the nation. The final 78-64 vote occurred on Friday afternoon—just one day after Florida approved its own law adding restrictions to voting by mail and drop boxes, and weeks after Georgia enacted a sweeping overhaul of its election system.

The Texas bill would ban election officials from sending out ballot applications to voters unless they specifically request one and grant more power to partisan poll watchers. The measure, which Democrats, corporations, and voting rights advocates have said impinges on Texans’ right to vote, will soon return to the Republican-controlled Senate and could still undergo significant changes. Republican Governor Greg Abbott has broadly expressed support for the bill.

Like the Georgia and Florida laws’ supporters, backers of the Texas bill have said their goal is to secure election integrity and restore trust in the electoral system, despite there being no evidence of widespread fraud in the 2020 elections. Hundreds of proposals to similarly restrict voting access are being considered in statehouses across the country.

On the Texas House floor, Democrats grilled Republican Rep. Briscoe Cain, a sponsor of the bill, about why he thought the restrictive voting measures were necessary after Texas’ Secretary of State declared that the 2020 election was free, fair, safe and secure. Democrats also took issue with the absence of a racial impact analysis in the bill, given Texas’ history of disenfranchising minority voters, and the harsh criminal penalties listed as punishment for violating the measures.

Democratic State Rep. Chris Turner called the bill a “straight-up assault on voting rights,” and asked Cain whether the bill is “simply a part and continuation of the Big Lie perpetrated by Donald Trump that somehow he really actually won the presidential.”

Cain responded that it was “not a response to 2020” and that a lot of these measures were a “long time coming.”

“I happen to believe that we don’t need to wait for bad things to happen in order to try and protect and secure these elections,” he said.

Abbott had made election integrity an emergency item in this year’s legislative session. During a March press conference in Houston, he asked the legislature to pass measures that would crack down on fraud caused by mail-in ballots and drive-thru voting. “Our objective in Texas is to ensure that every eligible voter gets to vote and that only eligible ballots are counted,” Abbott said.

About half of Republicans believe there is evidence that Biden did not win the 2020 election, according to a CNN poll conducted by SSRS in April, and Republican legislators across the country are pushing similar bills to ensure “election integrity.”

On Thursday, Florida’s Governor Ron DeSantis signed a voting bill that includes restrictions on drop boxes and voting by mail behind closed doors. The Florida voting law has already become the subject of a lawsuit from civil rights advocates, who argue that many of its components are unconstitutional. “Floridians can rest assured that our state will remain a leader in ballot integrity,” DeSantis said in a statement Thursday.

Texas is already one of the most difficult states in the country to vote in. Its voter ID laws require a photo ID or another document verifying their identity, like a current utility bill or bank statement. Voters can’t register online, and residents need to be registered to vote in Texas at least 30 days before Election Day.

One of the major focal points of the Texas proposal is voting by mail, which was used by 43% of voters nationwide in the 2020 elections, compared to 21% of voters in 2016, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Compared to most states, voting by mail is already tightly restricted in Texas. To be eligible, voters must be over 65, be incarcerated (but still eligible to vote), have a disability or illness or be outside their county during early voting and Election Day.

Supporters of the Texas bill worry that sending ballot applications out unprompted to voters could lead to people who don’t fall into the eligible categories to wrongly vote. Sen. Paul Bettencourt, an author of the bill, said during the governor’s March press conference that mailing out unsolicited mail ballot applications would have caused “voter chaos, because voters who have never seen this before would be thinking, ‘That’s what I should be able to do.’”

Voting rights advocates maintain that the application clearly explains who is and who is not eligible to vote by mail. They also say among the most chilling proposals in the bills are those that grant special rights to partisan poll watchers and make it harder for election judges to remove individuals being disruptive at polling sites. A proposal that was taken out of the bill, but could return as the Senate considers the measure, would have allowed poll watchers to videotape a voter at a voting booth if they believe assistance is being given unlawfully and as long as they don’t record anything on the voter’s ballot.

Supporters maintain that these protections are about transparency. “Poll watchers should be available to look at anytime and observe because that really is sunshine into the process and irrespective of party they should have… 100% access,” Bettencourt said.

But voting rights advocates like Anthony Gutierrez, executive director at Common Cause Texas, an advocacy organization focused on promoting democracy, point out that “in Texas, there’s a really long history of poll watchers inside poll sites disrupting voting and being problematic and needing to be removed.” Partisan poll watchers who were suspected of being affiliated with True the Vote, a nonprofit that grew out of a Tea Party group and is focused on rooting out fraud in elections, reportedly harassed voters in several minority neighborhoods in Harris County in 2010. As a result, the Harris County attorney created new guidelines dictating where watchers could be at polling sites and how close they could stand to voters while they cast their ballots.

On April 8, Common Cause published a leaked video revealing that the Harris County Republican Party is planning to mobilize an “Election Integrity Brigade” by building an “army of 10,000 people” to serve as poll watchers and election workers. The group said they are recruiting those who “have the ‘confidence and courage’ to go into some of Houston’s most diverse, historically Black and Brown neighborhoods to stop alleged voter fraud,” Common Cause said in a press release.

Lawmakers agreed to add several amendments to the measure on Friday, including adding language that election judges can call law enforcement to request a disruptive poll watcher to be removed and stipulating poll watchers cannot photograph private information or the ballot. Amendments were also added to ensure counties would be able to post basic information online about the election, such as its date, candidates and location of polling places, after voting rights advocates raised concerns that the initial bill language was overly broad.

A previous version of the bill included a ban on drive-thru voting, limitations on extending polling hours and a formula for the distribution of polling places that voting rights advocates say could lead to whiter neighborhoods getting more sites in larger, typically Democrat-leaning, cities. Those measures could be revived as the Senate reconsiders the bill.

Voting rights activists say Texas’ proposals are aimed primarily at Harris County, the state’s most populous county that enacted 24-hour voting, drive-thru voting and was planning on mailing out ballot applications to all registered voters unprompted during the 2020 elections until the Texas Supreme Court intervened. Harris County nevertheless went on to experience record-turnout, with more than 1.6 million votes cast.

“One of the themes coming off of last year’s election is that state leadership was very upset at everything Harris County did to make voting easier,” says James Slattery, an attorney with the Texas Civil Rights Project. The restrictions on mailing out ballot applications, for example, was “at least in part a reaction to Harris County” trying to send these applications proactively to every registered voter, he says.

Voting rights advocates are worried that the new restrictions, if they become law, will disenfranchise communities of color as well as senior citizens and disabled people by making it harder for voters to learn how to vote by mail.

Though Texas was not a swing state in 2020—Trump won the state by a margin of more than 5%—some say it could be the next Georgia if they can mobilize underrepresented communities, says Cliff Albright, co-founder of Black Voters Matter. “Texas is going to be the next test to see if this coalition—this Black, brown, younger voters progressive coalition—in a state that has traditionally been red is going to be able to shock the country and actually flip. That’s why they’re doing all this.”

The corporate backlash in the wake of Georgia’s election law, including Major League Baseball shifting it’s All-Star Game to Colorado, has sparked pressure from activists and subsequent statements from companies in many other states, including Texas. Republican governors and legislators are being forced to consider whether chipping away at voting access could cost them high-profile sporting events and conferences.

In Texas, both American Airlines and Dell Technologies, which are both headquartered in the state, were among the first to offer forceful statements against the proposed changes. “We are strongly opposed to this bill and others like it,” American Airlines said in a statement. “As a Texas-based business, we must stand up for the rights of our team members and customers who call Texas home, and honor the sacrifices made by generations of Americans to protect and expand the right to vote.”

Others have been less explicit. AT&T, also headquartered in Texas, said in a statement that “election laws are complicated, not our company’s expertise and ultimately the responsibility of elected officials…But, as a company, we have a responsibility to engage.” Over the last three years, AT&T has donated $574,500 to Abbott, Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick and sponsors of the voting bills, according to the newsletter Popular Information, which has been tracking donations to supporters of bills that would restrict voting access across the country.

Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell issued a statement in early April describing the corporate pushback on voting measures as “economic blackmail” that would result in “serious consequences.” Abbott has said companies in the state “need to stay out of politics, especially when they have no clue what they’re talking about.”

Rev. Frederick Haynes III, pastor at the Friendship-West Baptist Church in a predominantly Black and brown Dallas neighborhood, has been among those leading state-wide efforts demanding corporate accountability.

Companies like AT&T, which issued statements affirming that Black Lives Matter, “can’t have it both ways,” he says.““You can’t say Black Lives Matter. And then stand with those saying but your Black votes don’t matter.”