As Texas ban on abortion goes into effect, a religion scholar explains that pre-modern Christian attitudes on marriage and reproductive rights were quite different

The U.S. Supreme Court has failed to rule on an emergency application to block SB8, a controversial Texas law that bans abortions after six weeks of pregnancy. As such, the legislation went into effect on Sept. 1, 2021.

While signing the new law on May 19, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott stated: “Our creator endowed us with the right to life, and yet millions of children lose their right to life every year because of abortion.”

As Abbott’s words show, these kinds of draconian restrictions on women’s reproductive rights in the United States are often fueled by the belief of many Christians that abortion and Christianity are incompatible. For example, the catechism of the Catholic Church, an authoritative guide to the beliefs and practices of Roman Catholics, states: “Since the first century the Church has affirmed the moral evil of every procured abortion. This teaching has not changed and remains unchangeable.”

However, this statement tells only one part of the story. It is true that Christian leaders, virtually all male, have largely condemned abortion. Nonetheless, as a scholar of premodern Christianities, I am also aware of the messier realities that this statement conceals.

Celebrating women’s celibacy

The earliest Christian writings – the letters of the Apostle Paul – discouraged marriage and reproduction. Later Christian texts supported these teachings. In a second-century text known as the Acts of Paul and Thekla, a Christian author in Asia Minor praised Thekla for rejecting her suitors and avoiding marriage in favor of spreading Christian teachings instead.

In the third century, Thekla’s story inspired a Roman noblewoman called Eugenia. According to the Christian text titled the Acts and Martyrdom of Eugenia, Eugenia rejected marriage and led a male monastery for a time. Afterward, she discouraged Alexandrian women from having children, but this advice angered their husbands. These men convinced the emperor Gallienus that Eugenia’s teachings about women’s reproductive choice endangered Rome’s military power by reducing the “supply” of future soldiers. Eugenia was executed in the year 258.

Even as the Roman Empire became increasingly Christian, women still received praise for avoiding marriage. For example, the bishop Gregorios of Nyssa, an ancient city near Harmandali, Turkey, wrote the beautiful text Life of Makrina to celebrate his beloved sister and teacher, who died in 379. In this text, Gregorios admires Makrina for wittily rejecting suitors by claiming that she owed faithfulness to her dead fiancé.

To sum up, while early Christian texts did not exactly encourage women to explore sexual experiences, neither did they encourage marriage, reproduction and family life.

Choices beyond celibacy

Pre-modern Christian women had options besides celibacy as well, although the state, the church and mediocre medicine limited their reproductive choices.

In 211, the Roman emperors Septimius Severus and Caracalla made abortion illegal. Tellingly, though, Roman laws surrounding abortion were centrally concerned with the father’s right to an heir, not with women or fetuses in their own right. Later Roman Christian legislators left that largely unchanged.

Conversely, Christian bishops sometimes condemned the injustice of laws regulating sex and reproduction. For example, the bishop Gregorios of Nazianzos, who died in 390, accused legislators of self-serving hypocrisy for being lenient on men and tough on women. Similarly, the bishop of Constantinople, Ioannes Chrysostomos, who died in 407, blamed men for putting women in difficult situations that led to abortions.

Christian leaders often gathered at meetings called “synods” to discuss religious beliefs and practices. Two of the most important synods concerning abortion were held in Ankyra – currently Ankara, Turkey – in 314 and in Chalkedon – today’s Kadiköy, Turkey – in 451. Notably, these two synods drastically reduced the penalties for abortion relative to earlier centuries.

But over time, these legal and religious opinions did not seem appreciably to affect women’s reproductive choices. Rather, pregnancy prevention and termination methods thrived in premodern Christian societies, especially in the medieval Roman Empire. For example, the historian Prokopios of Kaisareia claims that the Roman Empress Theodora nearly perfected contraception and abortion during her time as a sex worker, and yet this charge had no impact on Theodora’s canonization as a saint.

Some evidence even indicates that pre-modern Christians actively developed reproductive options for women. For instance, Christian physicians, like Aetios of Amida in the sixth century and Paulos of Aigina in the seventh, provided detailed instructions for performing abortions and making contraceptives. Their texts deliberately changed and improved on the medical work of Soranos of Ephesos, who lived in the second century. Many manuscripts contain their work, which indicates these texts circulated openly.

Further Christian texts about holy figures suggest complex Christian perspectives on the acceptable termination of fetal development – and even newborn lives. Consider a sixth-century text, the Egyptian Life of Dorotheos. In this account, the sister of Dorotheos, an Egyptian hermit from Thebes, becomes pregnant while possessed by a demon. But when Dorotheos successfully prays for his sister to miscarry, the text treats the unusual termination of the pregnancy as a miracle, not a moral outrage.

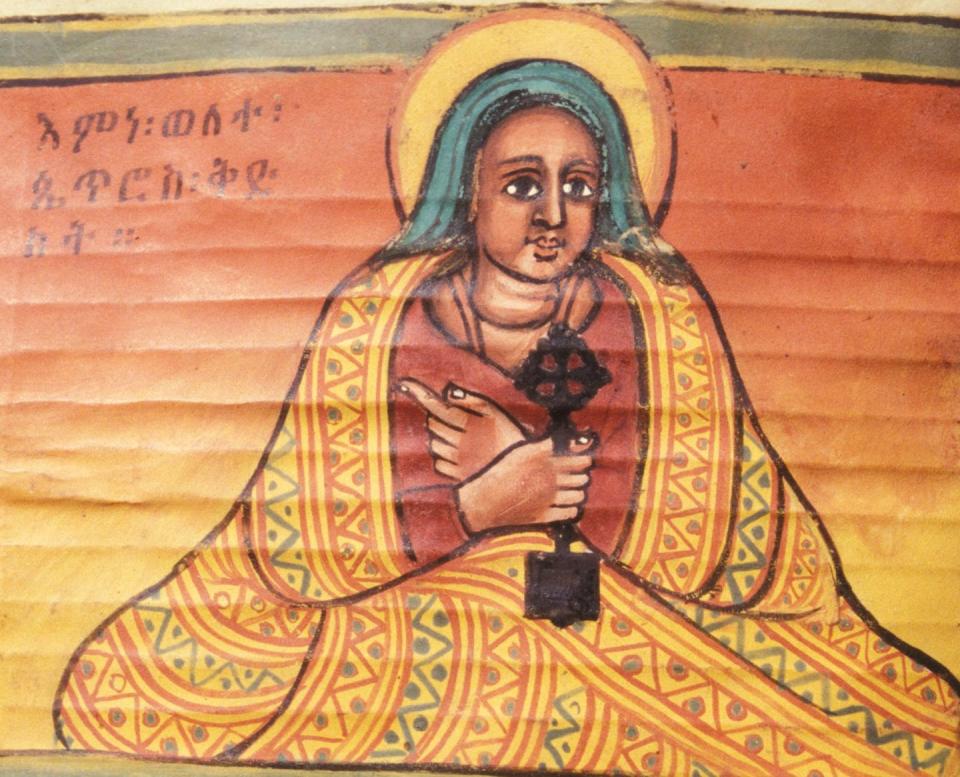

Around 1,100 years later, a similar event happens in the Ethiopian Life of Walatta Petros. According to this text, Petros, a noblewoman later canonized as a saint, married a general and became pregnant three times. However, every time she conceived, she prayed for her fetus to die promptly if it would “not please God in life.” The narrator tells us that all three children died days after birth, since “God heard her prayer.”

Certainly, Christians have a history of opposing methods for preventing and terminating pregnancies. But these pre-modern texts, spanning some 1,500 years, indicate that Christians also have a history of providing these services, and making them safer for women.

This tense and inconclusive relationship to abortion may be poorly known – or perhaps overlooked for political convenience. But that does not change the fact, as I see it, that Christians who support women’s reproductive rights are also following the historical precedent of their religious tradition.

[3 media outlets, 1 religion newsletter. Get stories from The Conversation, AP and RNS.]

This is an updated version of a piece first published on July 13, 2021.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. It was written by: Luis Josué Salés, Scripps College.

Read more:

How Catholic women fought against Vatican’s prohibition on contraceptives

Fundamentalism turns 100, a landmark for the Christian Right

Luis Josué Salés does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.