The Texas Bans on Abortion “Trafficking” Are Even Scarier Than They Sound

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

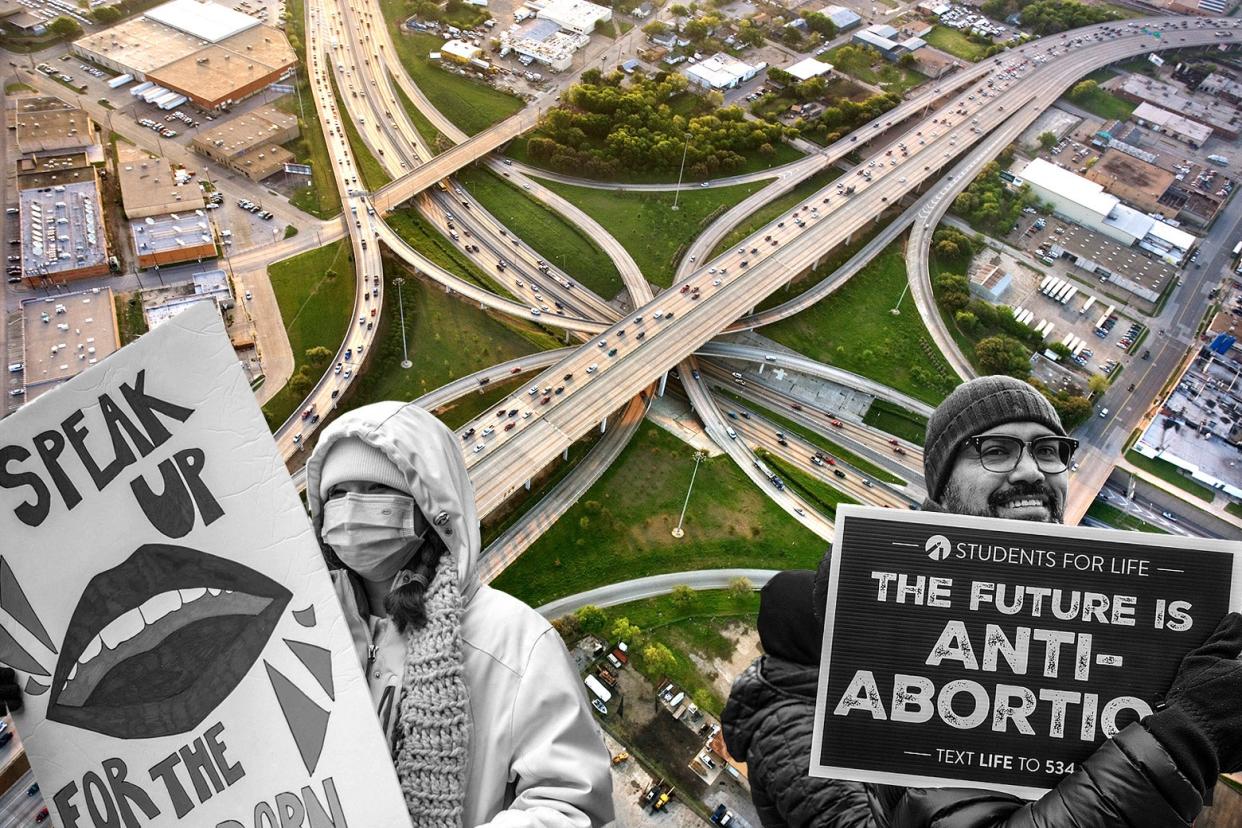

Last week, the Washington Post reported on a major new anti-abortion strategy: local “trafficking” laws that make it a crime to transport anyone to get an abortion on roads within city or county limits. Specifically, in certain counties in Texas, anyone can sue an organization or individual they suspect of violating the ordinance.

The architects of these laws, Jonathan Mitchell and Mark Lee Dickson, previously teamed up to create the roadmap for Texas’ bounty bill, S.B. 8. The success of that law, which made it past the Supreme Court prior to Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization and dramatically undermined abortion access before Roe v. Wade was even overturned, means that no one should dismiss this latest plan, even if Mitchell and Dickson’s focus on highways seems bizarre. And tactically, it is certainly a bit bizarre. Most abortions today involve pills—and organizations like Aid Access are effectively mailing them to patients in states where abortion is a crime. This ordinance does nothing to stop that. [Update, Sept. 7: The ordinances make it illegal to deliver or transport abortion drugs to any individual or organization within county lines, but as explained below there are many practical and constitutional obstacles to enforcement that the ordinances do nothing to resolve.] Enforcing the law will raise all kinds of other challenges. Ultimately, though, it could still offer a meaningful road map of where opponents of reproductive rights are going next.

Among the problems with enforcement is the question of how the ordinance and others like it could ever be enforced. How would anyone know if a driver on a road in or out of Texas is driving an abortion-seeker? By setting up a roadblock? Investigating everyone of reproductive age? None of that would be politically palatable—or financially feasible—for a state with a big budget, much less a small town like Llano or a rural county with limited resources. Besides, it’s hardly an efficient strategy for the anti-abortion movement: To build a “wall” limiting travel, abortion opponents need to pass ordinance after ordinance—and hope against hope that someone will enforce them.

So why bother with this kind of ordinance at all, when it does nothing to stop the mailing of abortion pills and seems impossible to enforce?

Obviously, fear is part of the point, as abortion fund leaders told the Post—even if you’re not going to be stopped and arrested while driving a friend to an abortion clinic across state lines, a vindictive partner could find your texts setting up the drive, sue you, and attempt to use geo-tracking data to collect in a civil suit. Still, it’s a circuitous road to enforcement. Perhaps the real significance of these laws is that they create room for abortion opponents to experiment. Dickson and Mitchell have successfully looked at small towns as laboratories for anti-abortion strategies in the past. In small towns, they can experiment with legislation that Republican lawmakers aren’t ready to pass at the state and federal levels and work out problems before the ordinances are ready for prime time. That’s what’s going on with these trafficking laws. Dickson and Mitchell have every intention of seeing them enforced, but they hope their movement comes out ahead even if enforcement is impossible.

First, the ordinance allows abortion opponents to figure out how to limit interstate travel without violating the U.S. Constitution—or at least being called on it. The trafficking laws try to do this by assigning enforcement entirely to private actors, just like S.B. 8, which will make it hard to get lawsuits into federal court. There are limits on when plaintiffs can seek relief against states in federal court—and one of the key exceptions involves state officials enforcing unconstitutional laws. But there seems to be no state official who can enforce this ordinance, just like the Supreme Court ultimately held to be the case with S.B. 8.

And there are limits on when states can enforce their laws outside state lines. If Texas tried to punish an abortion-seeker for getting an abortion in New Mexico, that would create all kinds of constitutional problems, potentially violating the right to travel, the due process clause, and even the federal full faith and credit clause, which requires states to honor court judgments and laws from other states. This ordinance tries to circumvent this problem by focusing on—or at least claiming to focus on—activity that takes place partly in Texas. It’s not clear that a state can punish someone for activity that is a right, not a crime, in another state, but Mitchell and Dickson are betting that conservatives will have the best chance if they focus on “crimes” that take place at least partly in red states. All of that adds up to the possible payoff for these ordinances: a trial run for other limits on the right to travel.

They are also trial runs for an enforcement strategy that relies on activist networks and personal rivalries. That’s how the federal Comstock Act, an anti-vice law that Dickson and Mitchell are also trying to revive, used to be enforced when it was otherwise impossible for postal inspectors to know what was in the mail. It’s obvious that a law like this won’t catch most abortion-seekers, but controlling husbands, angry exes, romantic rivals, and others could weaponize what they know and sue. Dickson had just this in mind when he described how the ordinance might get enforced, explaining, “A husband who doesn’t want his wife to get an abortion could threaten to sue the friend who offers to drive her.” Any abortion ban will be easier to enforce when private volunteers and vengeful acquaintances and family members step up to supply information.

Finally, every trafficking ordinance builds the case for later recognition of fetal personhood. In Dobbs, Justice Brett Kavanaugh stressed what he saw as a surge in sentiment that Roe had been wrongly decided: state laws that obviously conflicted with abortion rights and support from the Republican Party. To date, there is no equivalent right-wing swing toward the idea that a fetus is a rights-holding person under the Constitution—and that progressive abortion laws in states without bans are unconstitutional.

Dickson and Mitchell have ambitions to change that. The proponents of the ordinance stress that any travel for abortion involves trafficking, even if the abortion-seeker desperately wants to end a pregnancy. That’s because they focus on the fetus, not the pregnant patient—and argue that bringing a fetus across state lines violates the rights and personhood of the fetus. Even if the law is never enforced, it will be one more data point that anti-abortion activists can point to later when returning to the Supreme Court—and insisting that the conservative judiciary revisit the idea of personhood.

It’s worth remembering that this is hardly the only tactic that Dickson and Mitchell have in mind: They were the first to push the idea that the Comstock Act is a de facto national ban, a theory that has caught on with major anti-abortion organizations and is making its way through the courts. But on their own merits, these local laws are not as illogical as they may seem. Before Texas’ S.B. 8, it was easy to dismiss local ordinances as unenforceable publicity stunts. We all know how that story ended.