How this Texas boy could help change stroke protocols at Dell Children's and beyond

Like many 13-year-olds, Juan Amador loves to play video games. Fortnite is a favorite as is a Harry Potter game in which he plays in the house of Slytherin.

He's planning to spend this summer before eighth grade swimming near his home in Maxwell, halfway between San Marcos and Lockhart.

Unlike many 13-year-olds, Juan is recovering from a stroke he had on April 8, which paralyzed the left side of his body and made it difficult for him to talk.

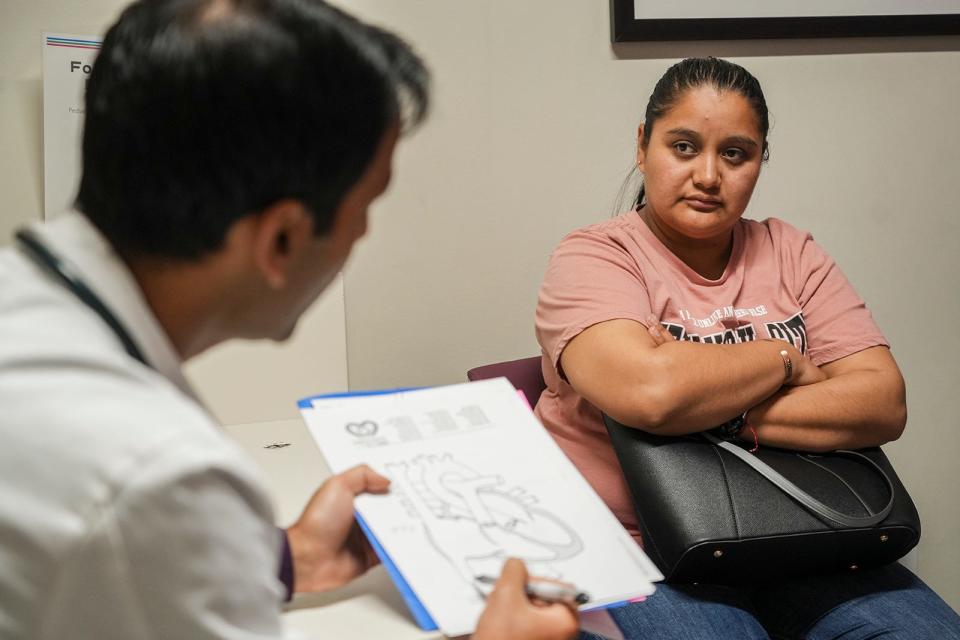

"We had never had anything like that happen," said his mother, Laura Rojas.

Strokes are not just for older people

Stroke in children "is far more common than people think," said Dr. Steve Roach, chief of UT Health Austin Pediatric Neurosciences at Dell Children’s. It's about 2½ times more common than a brain tumor in children, he said. At Dell Children's, "we've sometimes had as many as two in the same week."

Newborns are at the highest risk, happening in 1 in 4,000 live births, according to an American Heart Association/American Stroke Association report in 2019. After the newborn stage, the risks lessen to as high as 25 in 100,000 children, that report said.

Roach has been working on stroke care in children since the 1980s and he wrote the first statement on strokes in children for the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association in 2007. He also established Dell Children's stroke care plan, which he regularly sends to other children's hospitals.

Pediatric strokes: After a stroke as a baby, Austin boy gets surgery to separate the halves of his brain

The care plan is essential, he said, so everyone knows what to do when a child arrives with stroke symptoms.

If an adult arrives with these symptoms, Roach said, doctors think stroke. For a kid, there's a 50% chance it's something else, he said. The patient might get a CT scan but needs an MRI to rule out symptoms that could mimic a stroke, Roach said.

Children also tend to enter the hospital later with stroke symptoms than an adult, said Dr. Rachel Pearson, an adult vascular neurologist and the on-call doctor when Juan had his stroke.

He woke up like this

When Juan woke up the morning of April 8, he couldn't move his left side. He was having trouble talking. He had a headache. He was on the floor. The family called 911 for an ambulance. Rojas said she had to repeatedly explain that her son had the symptoms of a stroke.

Medics took Juan to the hospital in Kyle, where the adult stroke care team was called. Ascension Texas hospitals had done the early research into using tenecteplase instead of alteplase, both medications help dissolve the clot that causes a stroke. While both are given by IV, tenecteplase can be given at once, but alteplase has to be slowly administered during the course of an hour.

When Pearson was called, she used the research that had been done on adults and translated it to a pediatric patient. This meant doing an MRI to try to determine when the stroke had happened. With both alteplase and tenecteplase, there's a 4½-hour window from the time of the stroke to receiving the medication before it's unlikely to improve the symptoms.

"Time is brain," Roach said. "We're really under some pressure here."

Because Juan had woken up with the symptoms, no one knew exactly when the stroke happened. The MRI looked at his tissue and showed that the stroke had most likely happened just before he woke up.

They were still in the window for the medications.

Studying tenecteplase: Dell Medical School, Ascension Seton help reshape standards for stroke drug treatments

These types of medications have been studied in adults, not children. Both have Food and Drug Administration approval in adults, but not in children. The FDA does recognize an off-label use of alteplase in children. It does not for tenecteplase.

Because tenecteplase is newer, there aren't that many cases of it being used in children. A 2016 study in the journal Stroke estimated about 2% of children with an acute stroke have received tenecteplase as a treatment.

Pearson went with tenecteplase because that's what they had at the Kyle hospital. It also enabled them to quickly treat and transfer Juan to Dell Children's. She adjusted the medication dosage based on his weight.

While the Ascension Texas' adult hospitals have switched to tenecteplase, Dell Children's has stayed with alteplase. Because of this case, "we're now actively contemplating switching," Roach said.

The next step to recovery

Juan began improving with the tenecteplase. By the time he arrived at Dell Children's, he was able to move his left side. Another scan showed the clot was smaller, had moved into a smaller blood vessel, but not disappeared.

Dr. Jefferson Miley, a vascular neurologist, using a catheter, went in through Juan's femoral artery to the left side of the neck to reach the clot in Juan's brain. Using an aspiration pump, Miley grabbed the clot and pulled it slowly through the body until it came out through that same femoral artery.

"Immediately after, he was showing improvement," Miley said.

Rojas could see the improvement, but she said, "Juan looked scared. He wanted to go home."

While the clot was not big for an adult, it was large for a child, Miley said.

Without the medication and removing the clot, "this might have been a lifelong disability," Roach said. "He might have walked again, but he wouldn't be running."

Juan stayed in the hospital for seven days to ensure he had no lasting damage and to do rehabilitation.

Why did this happen?

Stroke in children is often caused by a clotting disorder, an infection or a congenital heart defect. A heart defect is the single biggest cause, Roach said.

In Juan's case, he had a hole in his heart, which was discovered when he was a baby.

Juan was born with pulmonary valve stenosis, which is a hardening of the heart valve going to the lung. Doctors at Dell Children's used a catheter with a balloon on the end to open up that pulmonary valve. "Since then, he's been doing really, really well," said Dr. Hitesh Agrawal, an interventional cardiologist at Dell Children's.

The team at Dell Children's thinks this is what happened to Juan:

A clot came from somewhere else in his body, went into the heart and through that hole. Instead of going to the lungs, which absorb most clots, the clot went to his brain.

Because of the hole in his heart, Juan remains at risk of a clot traveling the same path, Pearson said.

In August, Agrawal will run a catheter from Juan's femoral artery to the heart and deploy two metal structures that look like umbrellas on either side of the hole. Agrawal will leave those umbrellas in place. The heart tissue will grow over the umbrellas and seal up the hole.

"A one-and-done procedure," Agrawal said.

Back to being Juan

Juan's family says he has returned to normal. He's playing video games and watching TV. He goes for walks and plans to go fishing and swimming all summer. So how does he feel?

"Like nothing" happened," he said. "I feel good."

Know the symptoms of a stroke

Think of the acronym BE FAST:

Balance (loss of balance, dizziness or headache).

Eyes (blurred vision).

Face (one side of the face is drooping).

Arms (weakness in an arm or a leg).

Speech (difficulty speaking or understanding words).

Time (Time to call for an ambulance immediately to get help).

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Dell Children's looks at stroke treatments after Texas boy's case