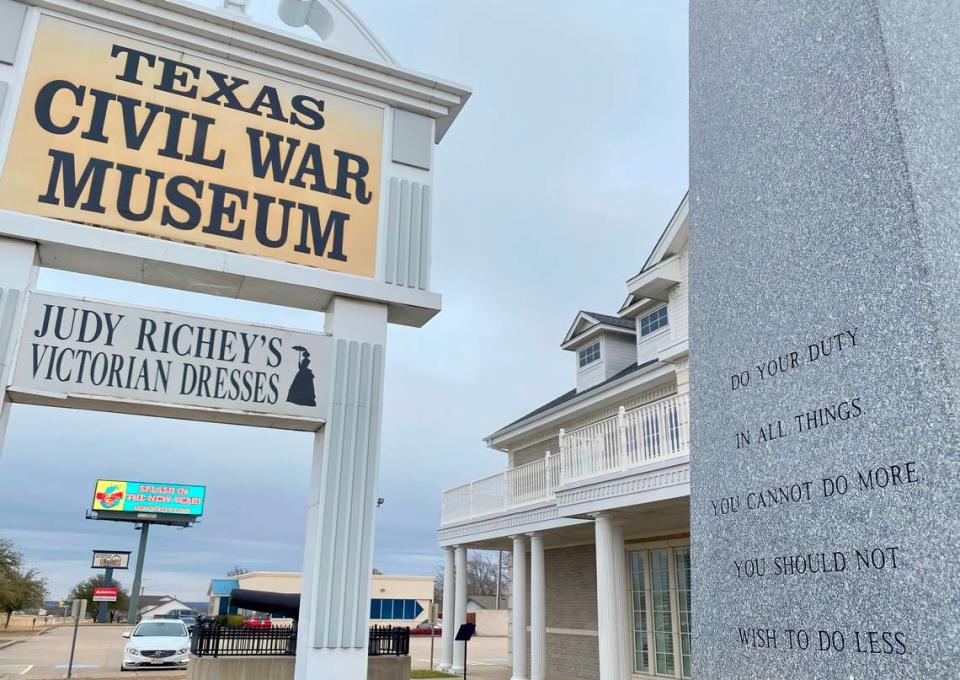

Texas Civil War Museum near Fort Worth is closing. It tried to be fair. But it failed | Opinion

The Texas Civil War Museum, meant as a nonpolitical exhibit on the South’s failed rebellion but inevitably tainted as a whitewashed attraction that overlooked Black history and the horror of slavery, will close Dec. 30, the museum has announced.

The museum’s Confederate and Union military artifacts, valued at $3 million when the $1.5 million building opened in 2004, are now worth $20 million-$25 million and “may be the biggest private collection ever put on the market,” said the owner of a Pennsylvania auction house.

Museum director Marcus Richey confirmed the closing, originally announced Feb. 20 on Facebook.

In 2004, founders Judy and Ray Richey set the goal of presenting an even-handed, professional museum collection.

They hired a National Park Service historian and scholars on the North and South, and they arranged the museum so antiques from the Union and Confederacy were split down the middle.

“It’s a very well-done museum, just remarkable,” said Sam Small, who is already selling photos from the collection through The Horse Soldier, a military antiques dealer in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

“I don’t know that anyone’s ever seen a collection like this.”

But over time, the Richeys’ noble goal of a neutral soldiers’ story told from “both sides” produced a military antique collection short on Black American history and eventually showing an overly romantic nostalgia for the South.

An introductory video, “Our Honor, Our Rights,” taught schoolchildren a monochromatic view of Confederate President Jefferson Davis’ foolish Lost Cause and ignored the reason behind the war over “states’ rights.”

(The “states’ right” Texas and the South defended was the right to own slaves.)

At one point, the museum’s gift shop devolved into a toxic Confederate battle flag trinket stand.

Oh texas civil war museum #thesouthwasright #notbias #butyouplayin pic.twitter.com/0JQLPZ87Iy

— PizzaPapi17 (@enriqueBOC) March 5, 2014

A museum volunteer also became swept up in promoting the seditious “Texit” campaign to promote a new secession and rebellion against the United States of America.

Yet the museum also presented a reputable collection of war antiques — uniforms, guns, even cannons — equally divided between the U.S. and the renegade Confederacy. It also featured artifacts from the U.S. Army’s all-Black buffalo soldier units and period dresses from the United Daughters of the Confederacy lineage society.

On TripAdvisor.com, visitors gave the exhibit four and a half stars.

“The quality of the exhibits is first rate,” one visitor wrote.

Another wrote: “This is great for reflection and I ask, ‘have we really learned anything?’ ”

But even on TripAdvisor.com, a now-former museum manager defended secession.

“America was an infant,” the manager wrote, “and needed those rebellious years out of the way to become an adult nation.”

In 2018, the museum accepted two historical markers removed from a Fort Worth city park. One of them remembered a violent East Texas Ku Klux Klansman who was implicated in an 1868 lynching, Confederate Brig. Gen. H.P. “Hinchie” Mabry.

Historian Don Frazier of Schreiner University in Kerrville has been the museum’s consultant and directed the video.

The museum was a “passion project” for the Richeys, he wrote by email.

“This impressive collection of artifacts and relics remains one of the truly great collections from that period of American history,” he wrote. “Times change, and the public’s interests change. Running a museum and stewarding physical reminders of the past is a challenge, and expensive, no matter the topic. The Texas Civil War Museum was a gift to the people of Texas and the citizens of Fort Worth and the surrounding area.”

He added: “There will never be another like it.”

Let us hope.