'That's what we do': These kids, teachers are making school work during COVID-19

Michelle Thompson can imagine her kindergarten students gathered around the tables that used to fill her classroom, building tiny houses from popsicle sticks, pieces of straw and toy cubes. She can almost hear their cheers when her wolf puppet fails to huff, puff and blow their structure down.

But since her school district in Broome County, New York, transitioned to remote learning in March, the art supplies and puppet sit, untouched, in cardboard boxes stacked high on a bookcase. They've been shelved along with all the other things needed to generate the learning-related excitement Thompson's husband, Erik, a high school science teacher, calls “the fizz.”

This year, “the fizz” is missing in classrooms across the country, whether they are empty like Thompson's, filled with socially distanced students or holding a combination of in-person learners and those crowded within Zoom boxes to learn remotely.

In the spring, months of school without "the fizz" failed to engage and educate students. With the coronavirus pandemic continuing, teachers and parents vowed to do better this fall. So the USA TODAY Network sent reporters into classrooms and students’ homes across the country to see how they were adapting.

Perhaps the biggest takeaway? The difficulty of the challenge appeared to be matched only by the resolve of the students and educators to make it work – and that's becoming even more crucial as a surge in coronavirus cases threatens to close schools again.

You see that resolve at Central Florida's DeLand High School, where Principal Melissa Carr begins the day at the school entrance, armed with a walkie-talkie and a thermometer she uses to check students' temperatures. Walking the halls later, she's forever breaking up clumps of students who loiter in violation of the school's new protocols about distancing.

“I believe that my staff will do anything that is asked,” she said, adding, "Our motto this year is 'Just keep it moving.' Let's do better today, because we don't know what tomorrow will bring."

Split attention: DeLand, Florida

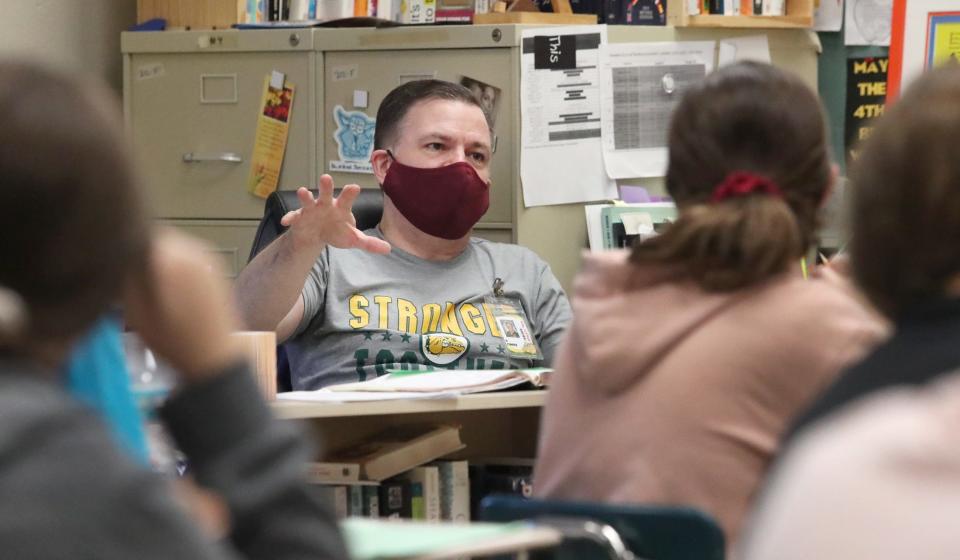

David Finkle is trying so hard to get students to talk.

The Central Florida teacher has about 20 sleepy teenagers spaced out in his room, wearing face coverings that make them even more inscrutable than usual. He also has 10 silent, faceless squares on his computer screen, students tuning into class via Microsoft Teams.

Volusia County, Finkle’s school district on the east coast of Florida surrounding Daytona Beach, allowed students who didn’t want to return to in-person learning to tune into class remotely. They follow the same class schedule as their peers but instead of walking the halls between classes, they switch to different video calls.

The mix is roughly 35,000 students in-person and 16,000 remote. Another 9,000 chose to switch to a fully virtual option that the district has always offered but never seen used in such numbers. With that option, they don't call in to a traditional classroom like Finkle's remote students do.

The setup leaves Finkle feeling divided, wishing there were two of him to be better able to help the two distinct groups of students in his classes at DeLand High School.

As it is, the students in the classroom can’t see or hear the students on his computer screen. The remote students can’t see or hear the students in the classroom. Finkle is generally confined to his desk in the corner, where the remote students can see him on his computer’s camera.

In 29 years of teaching, Finkle has never seen anything like this.

Struggling students:Bring them back to class -- or send everyone home?

He wants the students to share something they wrote with a partner, but the remote students can’t easily section off, and the in-person students aren’t supposed to get close to each other.

He wants them to share it with the whole class, but the remote students and the in-person students can’t hear each other and they’re all slow to volunteer.

He wants to show them something in a book but can’t find it – his collection is boxed away to limit the possibly germ-carrying items in the classroom.

He wants the remote students to open something he has projected on the board for the in-person students, but he has to pause and walk them through where to find the document.

He wants to show the remote students a quote taped on the wall and has held his laptop high above his head, asking, “Can you see that?” He gets silence back.

At the end of the school day, Finkle will go home and crash. He plans on a 15-minute nap, but it always turns into an hour. He used to run in the mornings after his alarm went off, but this year he has just been too tired.

After his first year of teaching, Finkle's position was eliminated, and he didn't return to the classroom until two years later. He's been thinking about that those years lately.

If not for that lost tenure, "I could have retired last spring,” he said. “And I might have been really tempted under the circumstances.”

Homeschool makeover: Indianapolis

“Roooar!”

Thwap, thwap, thwap.

“Owww!”

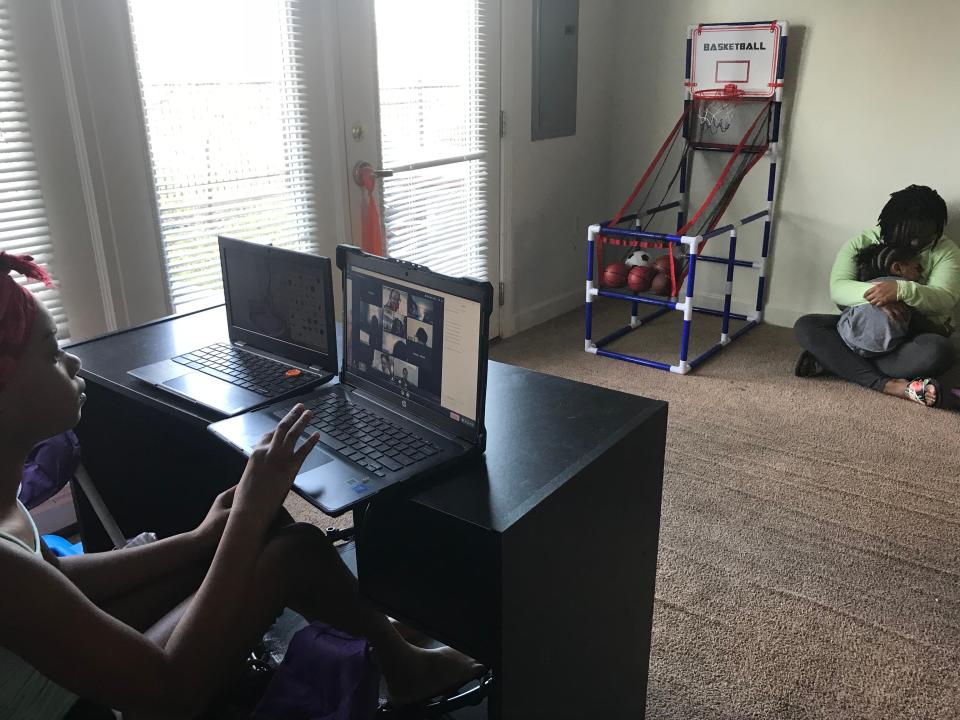

Kiymani Russell is trying to use the box method to solve a math problem that her teacher, Andrea Arms, is explaining from the front of her fourth-grade classroom at Edison School for the Arts. Kiymani sits at her dining room table, distracted by her 2-year-old brother, Randy, who’s hitting her with a plastic dinosaur.

“Rooooar!”

Swantella Nelson steps over and puts breakfast down in front of the toddler.

“Your sister is in school,” she reminds him.

Kiymani hits the mute button on her school-issued laptop while Randy says grace, which turns into "Patty Cake" somewhere in the middle.

She laughs at her little brother and then turns back to her math problem. Ms. Arms is telling the class to pat themselves on the back if they figured out that 342 times 6 equals 2,052. She checks her work and gives herself a small pat.

Kiymani is one of 11 kids in her class still attending school virtually. The rest returned to their classroom in mid-October when Indianapolis Public Schools reopened their buildings for in-person instruction. Indiana’s largest school district started the year online in mid-August, and about one-fifth of its students are continuing that way through the rest of the semester.

It wasn’t anyone’s first choice – not Nelson’s and certainly not her daughter’s. Some of Kiymani’s friends are among those who went back, and their excitement over new chairs that spin is almost too much to take.

“It seems fun to do it at the school,” she says wistfully.

But COVID-19 cases across Indiana are spiking, and the positivity rate in Indianapolis is climbing. Hovering around the target rate of 5% when the district decided to start bringing students back, it was greater than 7% by the time classrooms actually reopened for all grades, and last week it approached 10%. Nelson said she knows keeping Kiymani home is what’s best right now, even though that comes with its own set of challenges – like space.

An empty patch of beige carpet marks where Nelson’s couch once stood in the living room. She gave it recently to a friend who needed it more than she did. Working with less than 1,000 square feet, Nelson needed the space more than the couch in an apartment that has become a makeshift home office, classroom, art studio and toddler-sized basketball court.

After math class, the empty patch of carpet becomes the setting for Kiymani’s gym class. While half her classmates run around Edison’s school gymnasium, she and the other virtual students run in place at home. Her laptop is set up on the little desk that her mother uses as her own workspace. The lawn chair she uses as a desk chair is tucked under the other side.

“As much as I’d love for her to go back, I have to think about her health and safety,” Nelson says as she holds Randy at the dining room table covered in snacks and Kiymani’s school notes and tries to eat scrambled eggs that went cold an hour ago. Half of Randy’s breakfast had to be cleaned off the floor.

“It’s one of the hardest decisions I’ve ever had to make.”

It helped that the district made the decision for Nelson at the start of the school year. At-home learning in the spring didn't go well. At the time, the district didn't have enough laptops for all of its students, so elementary students like Kiymani were given paper learning packets. And Kiymani had a hard time accessing any extra virtual lessons because the family didn't have internet at home.

Even when companies were offering free internet for students, Nelson was blocked from accessing the program because of an outstanding balance on an old account with the only internet provider available in her apartment complex.

For the fall, the school district provided the family with a laptop and an internet hot spot. And the virtual lessons have gone well, Nelson said, even if there are distractions like little brothers with toy dinosaurs. So Kiymani will finish this semester online. Both mom and daughter hope they’ll be out of the house – working and in school – by spring.

A family affair: Binghamton, New York

Michelle Thompson arrives at the front door of Theodore Roosevelt Elementary School and raises her wrist in front of a temperature scanning device.

“Safe,” a detached voice says, confirming she is not running a fever.

She takes a step forward and tilts her head toward another scanner and uses a key fob to punch in for the day. An eerie quiet lingers in the hallways.

Her work day started at home at 4:30, the only time she had to schedule her class’ Zoom meeting, post the link and students’ assignments in Google classroom and update her calendar before she and Erik roused their daughters, Lydia and Norah.

The girls have been in remote versions of sixth and third grade since the beginning of the school year. A surge in community cases of COVID-19 in early October twice delayed their scheduled date for returning to school, which finally arrived Nov. 5. Now they attend school two days a week, going the other three to their grandparents' house. Erik's mother, Renee Thompson, is a retired kindergarten teacher.

The family of teachers knows how lucky the girls are to have this makeshift classroom, complete with a posted schedule and a folder of notes sent home to their parents every night. Some students are home alone with their siblings, others are in day-care centers or in difficult home environments, struggling to learn.

In her classroom that's empty on remote learning days, Michelle, 40, opens her laptop. Markers, art supplies and glue sticks have been pushed aside, leaving her with the small dry erase board on her desk, workbooks and a document camera. She opens the Zoom app on her computer, starts the meeting and greets her first-grade class.

Kids falling behind: Reading scores drop, math scores low. Will high school seniors be ready for graduation?

She has been working across grade levels since 2017 as a challenge enrichment specialist in two district elementary schools. But with COVID-19 restrictions and a limited supply of substitute teachers, her position has been eliminated. She's finishing up a temporary substitute position, and she's nervous about what happens when this job is done.

“I don’t know what I’m going to be doing next,” she said. “I have no idea.”

On the other side of town, in a classroom of the local Center for Career and Technical Excellence, Erik has once again been pulled away from his duties to fill in for a teacher who is absent.

As a science integration teacher, Erik, 41, usually bounces around to different classrooms, sharing science lesson plans with a range of departments from cosmetology to criminal justice. His lessons thrive on interaction, hands-on activities and shared experiences, like asking students to partner up and search for bacteria sources around the room.

The energy behind those interactive lesson plans is difficult to generate through a screen with remote students or in-person with students who have to maintain 6 feet of social distance.

He wonders about how much of the students' education is getting lost in the cracks of the hybrid learning model. He has given up on generating "the fizz."

“This year my attitude is, ‘I’m a teacher,’” he says. “A lot of people identify with their subject, but as a teacher we teach kids. That’s what we do.”

He’s setting new goals for himself, focused on a single question: “What can I do to improve the quality of a student experience?”

Feeling uprooted: Montgomery, Alabama

Some mornings these days LaMonica Cochran-Ray can’t remember where she and her children slept.

One week in October, Cochran-Ray, her 9-year-old son, Jeremiah, and her 3-year-old daughter, Ziah, stayed with a brother in Montgomery, Alabama, and an aunt and uncle 100 miles away in Georgia. By Thursday evening, they were back in Montgomery, in a hotel room.

They decamped Friday morning to the hotel lobby, where they could spread out at a long work table. Jeremiah needed to study for a math test, while Ziah practiced her letters.

So much movement adds to the challenge of setting up a remote classroom, but this time they’d remembered everything: laptop and charger, tablet, log-in password sheet. But before they could settle in, a new problem foiled them: faulty wiring meant the laptop charger wouldn’t work when plugged into the outlet closest to the big table in the lobby.

Instead, Jeremiah sat reading his new chapter book, part of an accelerated reading program, while his mother attempted to pull up some practice problems on her cell phone that he could copy onto scratch paper.

The need for such adaptability can’t all be blamed on the coronavirus. Cochran-Ray’s family has been on the move since July, when an area homicide set off a spate of shootings that forced them to flee after police warned her and the neighbors about revenge attempts from the victim's family.

Cochran-Ray was already coping with the effects of an accident last year, when she collided with a drunken driver who had pulled into oncoming traffic. Doctors have said she requires reconstructive back surgery, but the pain has prevented her from working her former job as a cosmetologist, and being out of work means no insurance. She manages the constant aches and sharp pain by rationing medication from week to week, storing up pills for days that are unbearable, rather than just aggravating.

Hope for a more settled life lies ahead. The family plans to move about 40 miles to Clanton, where Cochran-Ray has picked out a parcel of land for their modular home. But even with the move, she doesn’t expect their school days to get any easier.

This would have been the year Ziah entered Head Start, but between the move and COVID-19 concerns, Cochran-Ray chose to keep her out. Jeremiah, now a fifth-grader, is enrolled in Chilton County schools, where parents have a choice between in-person instruction or an at-home version the district calls blended learning.

Both the single mom and her son have asthma, and his is severe. Some mornings he can barely catch his breath and wears a nebulizer machine that allows him to inhale medicine through a silicone mask. So Cochran-Ray felt she had little choice but to keep him home, even as she struggles with guilt over her decision. While other children have returned to classrooms, met teachers and made new friends, Jeremiah has yet to even hear his teacher’s voice.

His classes are organized via a learning management system where teachers upload coursework and assignments. Students are given until 8 p.m. each day to check in and claim attendance. The system offers flexibility and the option to go at your own pace, which has been helpful given the family’s movements but also puts pressure on Cochran-Ray to be a full-time teacher, tackling everything from long division to natural science.

She worries Jeremiah isn’t as engaged at home as he was at school, where hands-on projects and demonstrations could excite his interest. And some of the third-party applications and websites can be glitchy. Last year Jeremiah received A’s and B’s. His latest progress report shows him with C’s. She’s holding off on a decision about what to do next semester until she sees what the county’s coronavirus case numbers look like this winter.

“Seventy-five percent of me wants him at home,” Cochran-Ray said. “The other 25 is thinking about what a 9-year-old needs. They need to interact. It's unfair for him, but the safety aspect weighs heavy on me.”

Before the pandemic set in, the family traveled often, visiting family in Chicago or driving to beaches on the Gulf Coast. Lately, Jeremiah has been dreaming of a visit to California and Australia when he’s older.

“I plan to write a book about five friends that travel the world,” he said with the sureness of a man with tickets already in hand. “I want to learn about the world.”

They do the best they can with what they have for now. In the hotel lobby, Jeremiah got started on his math problems while Ziah wore headphones, her tiny fingers wrapped around a tablet dressed in a bright pink sleeve. Her eyes filled with reflections from the screen before darting to her mother, to her brother then around the room.

The members of a girls volleyball team shuffled in and out, a coach shouting reminders to the players. Soon after, a hotel cleaner fired up an industrial vacuum.

Jeremiah worked along as if it were merely the hum of a distant wave.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY NETWORK: COVID school: Online class? In person? How kids, teachers make it work