'A year that's ripped my heart out': George Floyd family struggles with loss a year since killing

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

HOUSTON – LaTonya Floyd keeps a folded newspaper with a front-page picture of her brother’s killer in the center console of her SUV.

Each day, she stares into the eyes of Derek Chauvin, trying to decipher why the Minneapolis police officer kneeled on George Floyd’s neck for more than nine minutes while he was handcuffed and pleading for help until the life was snuffed out of him.

She has felt her share of anger toward Chauvin. But he has also helped keep her sane, LaTonya Floyd said.

“He gave me a reason to keep breathing,” she said. “I need to know why: What possessed you to kill my brother? Otherwise, I’d be in a mental hospital right now.”

To millions around the world, the final minutes of Floyd’s life, captured on a shaky smartphone video, reflected decades of police brutality against Black and brown citizens and unleashed global protests calling for racial justice. The police were called out to investigate a report that Floyd allegedly used a counterfeit $20 bill to pay for cigarettes.

Last month, Chauvin was found guilty of second-degree and third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter in the death of Floyd, 46. He awaits sentencing.

But for those closest to George Floyd, his death was a theft: the abrupt loss of a friend and confidant, of a fun-loving older cousin who swung you up toward the sky or sent Happy Birthday texts, of a lifelong friend who helped troubled youth give up their guns, of a brother who was always ready with a prayer and whose killing left a void stretching from Minneapolis to Houston’s Third Ward, where he grew up.

“It’s been a year that’s ripped my heart out,” LaTonya Floyd said.

The one-year mark of his murder will be observed Tuesday with a block party in the Houston housing projects where Floyd grew up. There will be other marches and events across the United States.

But few will experience the bile and pain of May 25 as heavily as his family and friends.

A brother before he was a case and a cause

Philonise Floyd, 39, has given so many media interviews about his brother’s death that he has lost count. There have been interviews with journalists from Japan, Brazil, Italy and Spain and radio shows where his words were simultaneously translated.

He readily shares the good memories of his brother. Like the banana-and-mayonnaise sandwiches he and George whipped up as kids. Or how they slept in the same bed growing up. Or how, as grown men, Philonese Floyd would be on long hauls as a truck driver and his brother would call him and pray with him over the phone. They’d pray that their mom, Cissy Floyd, would somehow swim out of the congestive heart failure that was slowly killing her or that a niece would get a high mark on an upcoming test at school or simply for the family's well-being.

Philonise Floyd marvels at the global movement birthed from his brother’s death. He and his wife started the Philonese & Keeta Floyd Institute for Social Change with the goal of advancing awareness on social justice themes. He has met with Vice President Kamala Harris and taken calls from activists across the globe.

“People around the world are going to cement his legacy,” he said.

Still, small things often overwhelm him. On a recent Monday afternoon, he visited Jack Yates High School in Houston’s Third Ward where he and his brother attended. A group of students showed him a video they had produced to promote an upcoming memorial walk for his brother. The two-minute video showed footage of Floyd pinned under Chauvin’s knee while students repeated things he had said in his final minutes of life: “I can’t breathe.” “Tell my kids I love them.” “Mama, mama.”

Philonise Floyd broke down and cried.

“To everybody else, this was a case and a cause,” he said. “But to me, that was my big brother.”

The whole world watches you grieve

For months, Tiffany Cofield managed to push the thought of the murder of her longtime friend out of her mind. He was away in Minnesota, she kept telling herself, more than 1,100 miles north of her hometown of Houston. That’s why he hasn’t called or why the funny, uplifting Instagram messages abruptly stopped.

But then, last month, she accompanied the family to Minneapolis for Chauvin’s trial. And as the plane touched down, her new reality crashed into focus: George was truly gone. The eyes of the world were on that courtroom, she said, as Cofield huddled with the Floyd family to await a verdict. As the jury deliberated, Cofield was gripped by an anxiety attack and had to be helped out of the courtroom’s overflow room.

“I know what it feels like to have the world watch you grieve,” she said. “That’s something I would never wish on anyone.”

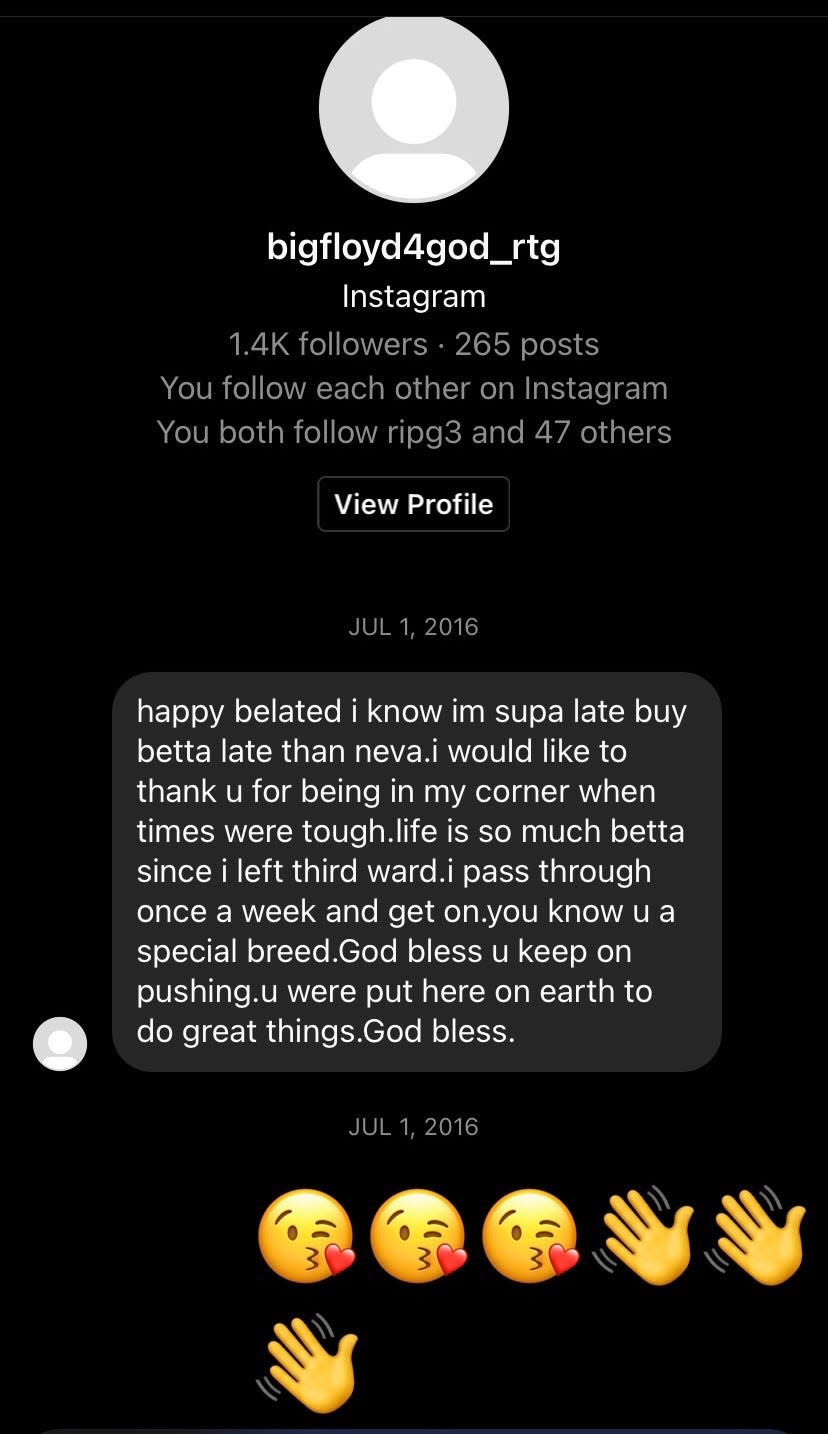

For the past year, Cofield, 36, has lived with a tight ball of anger in her chest. In June, she celebrated her first birthday in more than a decade without a text from George or a call from him on Christmas morning. She misses his Instagram messages, which were sometimes uplifting, often funny.

One from 2016 read, “You know u a special breed. God bless you keep on pushing. u were put here on earth to do great things. God bless.”

She’s inspired by the global attention, how it has motivated millions to march. But that doesn’t bring him back, she said, nor soothe the gnawing anger inside her.

“I’m angry because it was senseless,” Cofield said. “I’m angry because it wasn’t worth it. I’m angry because it was just a $20 bill.”

Grieving has no time limit

Brooke Williams, 17, remembers the fun chaos of living in a four-bedroom, wood-frame home in Houston’s Third Ward with four siblings, an aunt and three uncles, including George. Her grandmother, Cissy Floyd, was constantly cooking up steaming vats of smothered pork chops, gumbo, collard greens and cornbread to feed everyone. Family members slept two or three to a room.

Brooke remembers how she would come home from school and George would swoop her up and swing her toward the sky, causing her to explode into giggles. Or lift her and her sisters inside the house so they could pretend to crawl on the ceiling like Spider-Man.

"He loved to see others happy,” she said.

After dinner, they would gather around the one television to watch the Houston Rockets play. George would get Brooke to scratch his head until he dozed off to sleep. It happened so often that he came up with a song to entice her:

Scratch my head, scratch my head, yeaaah…

Scratch my head, scratch my head, yeaaah…

George was the first to put a basketball in her hands and show her how to dribble. Today, Brooke, a junior, is on the varsity basketball and track and field teams at Jack Yates High School.

The past year without her uncle has been devastating, she said, a loss felt most succinctly in October. Brooke’s birthday is October 13, one day before George’s. Each year, George would send her a birthday text and she would respond the next day. Last year, there were no birthday text exchanges.

“I miss his hugs. I miss his love most of all,” she said. “And his laugh. He had such a deep laugh."

Since her uncle’s murder, Brooke said she leaned on her family for support. The anniversary will be filled with celebrations of his life and good friends remembering the best of George Floyd. But it won’t end their pain, she said.

“Grief doesn’t have a time limit,” Brooke said.

Something to pass on to our children’s children

The last time he saw him alive, George Floyd was in Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church, making copies of fliers for his mother’s funeral, childhood friend Chris Johnson said. It was the same place where, years earlier, he and George had gathered to minister young people in Houston’s Third Ward.

Johnson, 39, a pastor at Good Hope, knew George growing up but really got to know him later in life when the two teamed up and strolled through the Cuney Homes housing project, known locally as “the Bricks,” persuading troubled young people to drop out of gangs and turn their attention to God. George Floyd, a towering figure at 6 feet, 6 inches and former football standout at Jack Yates, carried the street cred to sway local kids, Johnson said.

“George Floyd was investing in people long before he became a global name,” he said.

Like others, Johnson said he has marveled at the backlash against police brutality Floyd’s death has unleashed. He called it this generation’s “watershed moment,” akin to the assassinations of Emmett Till or John F. Kennedy, which sparked civil rights action.

But all the marches and events surrounding the anniversary of Floyd’s death will be for naught unless long-term, substantive changes take hold, he said. On Tuesday, he plans to lead a roundtable discussion of the long-term impact of Floyd’s death with a cross-section of local leaders: Black, white, Latino and Asian people of varying socioeconomic backgrounds.

“The biggest tragedy would be if we don’t all collectively reflect on what all this means,” Johnson said. “Our children’s children’s children will be talking about this.”

A second birthday

LaTonya Floyd still talks to her brother each day. She tells him the impact he has had on people here and asks how their mama’s doing up there. Each day, she cries, remembering she won’t ever hear George's voice or see his smile again.

“I don’t wake up feeling the same. I don’t go to bed at night feeling the same,” LaTonya Floyd, 52, said. “My life has changed dramatically.”

The good memories are still there and she keeps them close, like tiny treasures. Memories of George scampering around the living room in diapers. Memories of teaching him the lyrics to REO Speedwagon and Whitesnake songs and singing them together. Memories of sitting with a grown George Floyd on the porch of her home, as his daughter, Gianna, ran and squealed nearby.

“It was magical,” LaTonya Floyd said. “The furthest thing from our minds was that he’d be taken away from us.”

The past year has been full of pain and grief and tears. But there have also been surreal moments. When members of REO Speedwagon read in a People magazine article that LaTonya Floyd and George Floyd often sang their songs together, the band’s lead singer, Kevin Cronin, flew to Houston last month to surprise LaTonya Floyd at a vigil for her brother.

Onstage at Houston's Community of Faith Church, LaTonya Floyd and Cronin belted out a rendition of “Keep on Loving You.” The scene, captured by local TV crews, shows LaTonya Floyd initially giggling and hesitant but then leaning into her mic and singing with abandon, pumping her fist and pointing at the ceiling as she rolls through the lyrics with Cronin:

Cronin later presented LaTonya Floyd with a signed platinum record of the song.

“It was amazing,” she said.

LaTonya Floyd still hasn’t seen the smartphone video that ignited the protests and led to Chauvin’s conviction. Won’t see it, she said. Still too painful.

She heard parts of it when prosecutors played it in court. The voice of her brother pleading for help billowed the sharp pain she keeps deep inside. If she could have switched places with him, she said, she would have.

“He suffered. It’s all I could think about,” she said, wiping away tears. “I just want to hold him and I can’t.”

For the anniversary, she plans to mingle with throngs of people in the Third Ward to celebrate his life. She’ll carry a large black-and-white painting of her brother wearing a white baseball cap emblazoned with a black fist holding the scales of justice and “I Can’t Breathe” written on the side. A halo floats over his head and a single tear falls from his right eye. LaTonya Floyd is pictured on the bottom-right of the portrait, looking over her little brother.

She’ll share memories and dance a little and probably say a few words. Later, she’ll drift away from the crowds and find a quiet spot to talk to her brother. She’ll tell him about the celebrations – and how he now has two birthdays.

“October 14 is the day he was born and May 25 is the day that he was reborn. He’s truly an angel.”

Follow Jervis on Twitter: @MrRJervis.

MORE IN THIS SERIES

George Floyd's murder generated outrage — and lots of soulful art

After George Floyd, other families demand justice after police killings

'A year that's ripped my heart out': George Floyd family struggles with loss a year since killing

One year later: Photos show a racial reckoning after George Floyd's death

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Before he was a headline, George Floyd was a friend, brother and uncle