Thieves destroyed League 42 statue of Jackie Robinson. We must respond with hope. | Opinion

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The theft of the Jackie Robinson statue from the League 42 baseball fields brought to my mind one of the most embarrassing mistakes I ever made as a journalist.

I was the 24-year-old editor of a small weekly called the San Fernando Sun, in San Fernando, California.

And one dark and stormy night (with apologies to Snoopy), someone stole the American flag that flew over the San Fernando Pioneer Cemetery, the final resting place of the city’s founders, fallen soldiers and veterans from the Civil War, the Spanish-American War and World War I.

I was outraged, and I pounded out a scathing editorial that ended thusly: “No one stoops so low as when they climb to steal the flag from over the graves of our honored dead.”

The next, day, I got a call from a man who said “I’ve got that flag you wrote about.” Turns out he was a Vietnam veteran and was upset that the flag was being flown in the dark and the rain and he took it down because he felt like it was dishonoring the flag and the people buried in the cemetery.

It was an embarrassing retraction for me, but it taught me a valuable lesson: When opining in print, try not to jump to conclusions, because sometimes there’s more to a story than you know.

That said, today, as I contemplate the theft of the statue from League 42, I am feeling the same burning, seething outrage that I felt as a young editor almost 40 years ago.

Only this time, I write with confidence that there’s no good explanation, no redemption, no quick fix, no happy ending.

On Monday, Wichita police released the news that the pickup truck believed to have been used to heist the statue had been located and impounded.

My hope, and a lot of people’s, was that it would lead to the recovery of the sculpture — which had been cut off at the shoetops — and that it could be repaired and reinstalled at a reasonable cost.

Metal theft is common in Wichita, but this is something far more sinister than sawing off a catalytic converter or swiping a roll of copper tubing from a construction site.

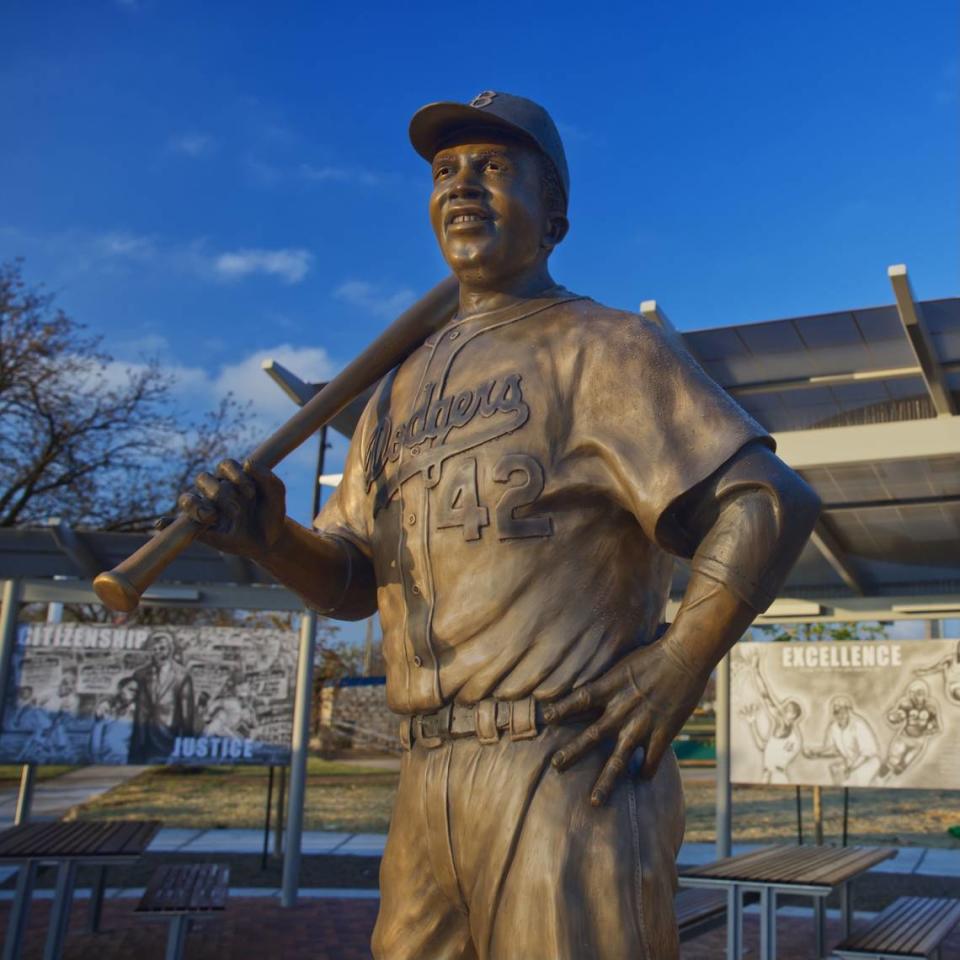

League 42 — named for Robinson’s uniform number when he became the first Black player to get into the Major Leagues — is based at McAdams Park in the heart of Wichita’s Black community.

The league’s $30-a-family registration fee, which includes uniforms and equipment if needed, offers 5- to 14-year-olds from low-income families the opportunity to play organized ball without their parents having to shell out hundreds of dollars they can’t afford.

We all know the story of Robinson breaking baseball’s color barrier in 1947.

But there’s more to it than that.

I came to Wichita from the position of city editor at the Pasadena Star-News, where I was steeped in the complicated racial history of Jackie Robinson and his family, who moved there when he was a child.

Pasadena is a city of contrast. Half of it is old-money, white-shoes affluence, the Pasadena you see on New Year’s Day represented in the Tournament of Roses Parade. The other half is historically Black, and much poorer.

A freeway runs between the two parts of the city and divides them from each other.

Sound like anyplace you can think of off the top of your head?

Jackie died in 1972, years before I came to Southern California. But he had a brother Mack who stayed in Pasadena, crusading for civil rights in his hometown, and dying there in 2000, two years after I came here.

Like Jackie, Mack was a standout athlete at Pasadena City College — once one of the fastest men in the world.

At the Berlin Olympics in 1936, he won a silver medal in the 200 meters, coming in second only to the legendary Jesse Owens — a one-two sweep on the world stage that was the perfect refutation of Adolph Hitler and his delusions of Aryan racial supremacy.

When Mack Robinson returned home to Pasadena, the city handed him a broom and put him to work sweeping the streets. He would wear his Olympic team jacket to work, an act of silent protest that angered the racists who ran City Hall.

Even that “honor” was short-lived. In 1939, when the NAACP sued to desegregate the municipal swimming pool, the city retaliated by firing all its black employees, Mack Robinson included.

As Jackie’s legacy grew to legendary proportions, the city sought to belatedly claim him as a favorite son by naming things after him.

Old-timers at the paper told me the stories of how he always turned down those ceremonial invitations as a matter of principal, in part because he felt Pasadena remained a bastion of racism and the honors were insincere, and in part because of the way the city treated his brother.

Today, we can, and we must, honor the Robinson legacy and inspire this community’s children with his ideals.

The first step is to restore the statue of Jackie Robinson to its place of honor in McAdams Park.

And that’s going to take money. The statue was valued at $75,000.

There are two avenues to donate - a League 42 site at shorturl.at/dgAWZ, or a Go Fund Me page at https://gofund.me/5ca3c7fb.

On Sunday, I made $150 guest-preaching at the Kechi United Methodist Church. I donated that money to the statue restoration project, and invite you to join me.

Because no one stoops so low as when they bend down to saw off a statue representing our children’s hopes and dreams.