Thieves are stealing checks from USPS boxes. 'Mailbox fishing' — or an inside job?

JERSEY CITY, N.J. — Perched on the corner of a quaint downtown block in this northern New Jersey city, it stands ready to serve the community from morning to night and through rain, sleet and snow.

A royal blue U.S. Postal Service mailbox.

For nearly two decades, a USPS collection box has stood along Pavonia Avenue at Coles Street, safeguarding the precious correspondence of countless residents.

But now some locals treat it like a pariah.

“I stopped putting checks in that mailbox,” Vinod Dadlani said.

“Never again,” Paul Albasi said.

The two men are victims of baffling and still-unsolved crimes. Checks they dropped in the box were stolen, altered and cashed.

The thief who made off with Dadlani’s check scored $4,819.

Whoever took Albasi’s got $4,901.33.

In both cases, the crooks inflated the dollar amount on the checks and wrote a different name in the payee line.

Dadlani and Albasi ultimately got their money back, but the ordeal was time-consuming and emotionally draining and left them vulnerable to identity theft.

And they are far from alone as victims.

Numerous Jersey City residents have had checks stolen in the past year, and the thefts are not confined to one particular mailbox. Checks have been intercepted, altered and cashed after they were placed in envelopes and dropped in at least two other nearby USPS collection boxes.

The crime is not unique to Jersey City.

The Boston area was hit by a rash of thefts at USPS boxes in February. Roughly $200,000 in checks were stolen from a collection box outside a New Orleans post office that same month. And the situation got so bad in Peachtree City, Georgia, that police warned residents to stop dropping their mail at the main collection box.

“That’s right do not, stop, don’t do it, halt, blockade, cease, discontinue, freeze, terminate, placing any mail you don’t want stolen from the big blue mailbox in front of the United States Post Office located in Peachtree City,” the police department posted on its Facebook page.

The thefts raise fresh questions about the security of the U.S. mail system at a time when the Postal Service is under intensifying scrutiny over its ability to move and safeguard mail-in ballots for the 2020 presidential election. President Donald Trump has claimed that the increased use of mail-in ballots will lead to fraud even though numerous studies and reports have found there’s no widespread evidence of voter fraud in the U.S.

The available data suggests that thefts at USPS collection boxes — at least the ones that are reported — are relatively uncommon.

In recent years, the problem seems to have been concentrated in the Northeast. Nationwide, there were 2,881 reports last year of people illegally pulling mail out of collection boxes, according to U.S. Postal Inspection Service data obtained in a Freedom of Information Act request. More than 1,530 of them were in New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

The postal inspectors have received 1,395 reports across the nation so far this year.

In Jersey City, some theft victims have been trying to sound the alarm for months. But it’s an unusual kind of crime wave: Because most victims are eventually made whole — banks typically refund the money — authorities have less incentive to hunt down the thieves.

Many residents, in fact, are unaware of the problem. So was I — until it happened to me.

An age-old crime

Mail theft is about as old as the postal service itself.

In 1793, a man named Noah Webster, who would later become known for publishing “Webster’s Dictionary,” was recruited by the postmaster general to investigate a series of mail thefts between New York City and Hartford, Connecticut.

Since the turn of this century, sidewalk mailboxes have seen decreasing traffic thanks to the rise of email and online banking. But old habits, like dropping a rent check or water bill payment in the mail, die hard, and the collection boxes remain an attractive target to enterprising thieves.

In late 2016, reports of mail theft began pouring into the New York division of the U.S. Postal Inspection Service, according to spokeswoman Donna Harris.

An investigation soon determined that the thefts were taking place at street corner mailboxes in the Bronx. Most of the bandits were found to be employing a tactic known as mailbox fishing, in which they use handmade tools to pluck envelopes out of the collection boxes.

The “rod” generally consists of a string tied to a sticky rodent trap or bottle slathered in glue. The thieves drop it into the box’s pulldown lid, reel it in and sift through their catches in a search for cash, checks or anything else of value.

Washing ink off checks requires little scientific know-how, experts say, and can be done with common household cleaning products. The criminals write a new name on the check and can change the value to whatever they want.

To combat the problem, the postal service modified the sidewalk boxes in New York in an effort to make them more secure, Harris said.

But the changes didn’t work. Thieves still found a way to pull out the mail, Harris said.

The postal inspectors, operating in tandem with the NYPD, went to work to investigate and bust the thieves. The strategy yielded results but it, too, didn’t solve the problem.

“We arrested over 100 people,” Harris said. “But we realized we weren’t going to arrest our way out of the situation.”

So the postal service shifted strategy: Instead of pouring more resources into trying to hunt down all of the bandits, it focused on building a fishing-proof mailbox.

The new contraptions were rolled out in the New York-New Jersey area in early 2019. Gone were the pull-down lids exploited by the thieves. They were replaced by a tiny opening just large enough to fit an envelope, giving each sidewalk mailbox the feel of a vault.

“We like to call it the Cadillac of mailboxes,” Harris said.

The postal service spends $700 to $1,200 to replace old boxes with the Cadillacs, according to George Flood, a postal service spokesman. That means it cost $4.9 million to $8.4 million to replace all 7,000 boxes in New York City alone.

Soon after they were installed in New York, reports of theft plummeted, Harris said.

But the situation has played out differently in Jersey City. The mailboxes in the Hamilton Park neighborhood, where residents have reported thefts, are all the newer models designed to foil mailbox fishing.

So how to explain the thefts?

Gregory Kliemisch, a postal inspector and public information officer in the service’s Newark division, which oversees Jersey City, declined to answer specific questions about the incidents.

“We’re not being evasive because we have anything to hide,” Kliemisch said. “But in the realm of an investigation, there’s sensitive information that could jeopardize the bigger picture.”

The thefts raise uncomfortable questions for a financially strapped federal agency already under siege.

Are the Cadillacs of mailboxes more like jalopies?

Or is it an inside job?

'It was terrifying'

Tom Gibbons, a real estate broker, lives just across the street from the mailbox on Pavonia Avenue.

He grew suspicious in recent years after several Netflix DVDs he dropped off at the box — a pre-Cadillac model — failed to reach their destination. Gibbons said he went to inspect the box one day last summer and couldn’t believe what he discovered.

“I opened up the lid and reached in and the lower edge of the lid was completely sticky,” he said.

It didn’t take long for Gibbons to identify what it was. “Doublesided duct tape,” he said. “In fact, there was an envelope stuck on it.”

Gibbons said he contacted the postal service. A few months later, the box was replaced by one of the newer ones designed to be more secure.

“I thought that should solve the problem,” Gibbons said.

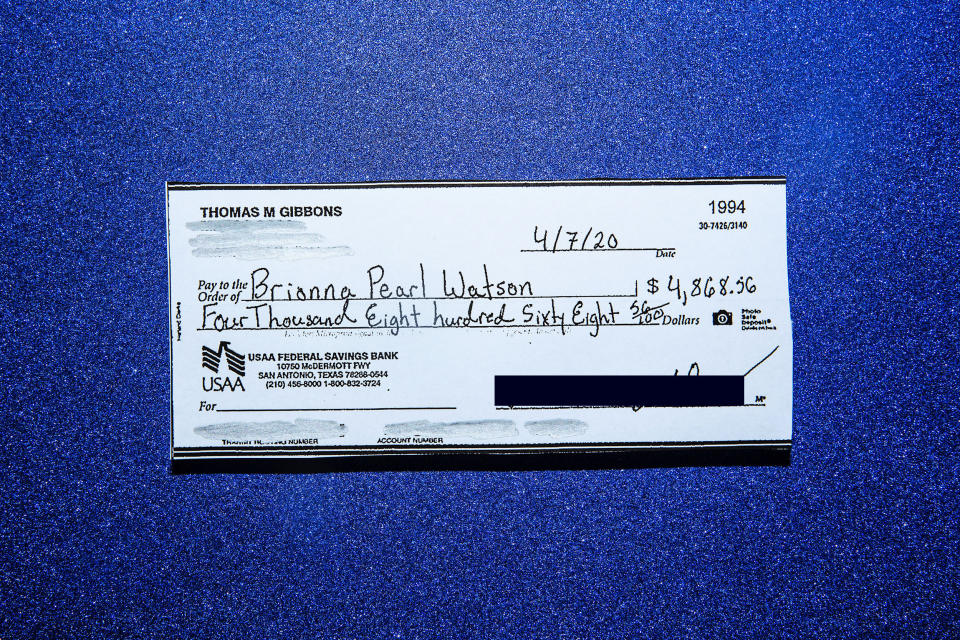

But this April, he dropped into the mailbox an envelope with a $272 check inside to pay his water bill. He pulled up his mobile bank account a day or two later and saw a transaction that alarmed him: a check worth nearly $5,000.

Gibbons phoned his bank and it emailed him a copy. The name of the water company was gone. In its place was the name of a person he didn’t know: Brianna Pearl Watson.

The amount was also changed: The $272 had been erased. The value of the check was now $4,868.56.

Gibbons reported it to the police and the postal service. Then he typed up a post about his ordeal on the hyper-local social media site Nextdoor.

In a few days, more than 100 people had posted replies, many of them sharing stories similar to his.

“I was really just shocked to see the response,” Gibbons said.

One of the people who posted was Corey Eisenstein, who was victimized not once but twice.

Eisenstein was planning a wedding with his then-fiancée Kate Goss in March 2019 when he dropped a $5,000 check in the mail to reserve the venue. About six weeks later, someone from the venue got in touch with him and asked when he was planning to send the deposit.

Eisenstein was confused — the check had already been cashed. But when he and Goss pulled up the image of the check online, they instantly suspected that something was amiss.

The space where she had written the name of the venue, a farm in Hudson Valley, New York, now had a name they didn’t recognize: Peter T. Pinckney.

They contacted the venue and asked if someone with that name worked there.

“They said they never heard of him,” Eisenstein recalled. “And now there was a panic because we didn’t know if we were going to have our venue, and we didn’t have any money.”

Eisenstein and Goss were also perplexed as to why the check was cashed in the first place. The name, Peter T. Pickney, was the only section that was altered and it bore almost no resemblance to the handwriting elsewhere on the check.

He and his wife spoke to the issuer of the check, Chase Bank, and were told an investigation would be opened and a decision would be made on whether to return the missing funds within 30 days, according to Eisenstein. On day 30, the bank informed them it would return the money, Eisenstein said.

Eisenstein said he filed a report with the Jersey City Police Department and the Postal Service. He informed both agencies that he had dropped off the check at the mailbox on Monmouth Avenue at Seventh Street, less than two blocks from the box on Pavonia Avenue.

“This is the largest check we’d ever had to mail, and it happened to be stolen,” Eisenstein said. “We didn’t know initially if it had been taken from the mailbox.”

If it had been plucked out of the box, the couple soon had reason to believe it wouldn’t happen again.

The mailbox was replaced a month or two later with the more secure model. He and Goss got married in September and went back to mailing their rent checks there.

They each put separate checks in a single envelope — they split the rent — and mail it off each month. But in January, the couple’s landlord told them he had never received their November rent payment.

Eisenstein checked his bank account and saw that the check was never cashed. Goss checked hers and saw that it was. The landlord’s name was gone. In its place was the name Richard William Kleine.

“It was terrifying,” Goss said. “I couldn’t believe this was happening again.”

The couple went to the local Chase branch to report what happened. When the teller told them where the check was cashed, they were shocked.

It wasn’t some hole-in-the-wall check-cashing store. It was a bank. The very bank in which they were sitting, in fact.

The couple recall posing a question to the teller: Doesn’t that mean you would have this person on video?

“Our curiosity about who cashed the check didn't seem to be something they were interested in satisfying,” Eisenstein said. “They said they were going to handle it internally.”

The money was ultimately returned to Goss’s account. Since then, the couple has stopped mailing checks from any of the boxes in the neighborhood.

A Chase spokeswoman confirmed that the $1,000 check was cashed at one of its branches. The person who cashed it presented two forms of identification: a North Carolina driver’s license and an ATM card with signature.

“Upon investigation, we confirmed the customer signature listed on the disputed checks did not match the client’s signature on previous authorized checks or what we have on file,” the spokeswoman said. “The check handwriting and format did not match any of our customers previous check items, and the customer was issued a credit to her account.”

But the spokeswoman said she could not provide any information on the person who cashed it.

Gibbons also got his money back. He said he doesn’t understand why it’s taken so long for the thieves to be caught.

“It’s just a matter of devoting the resources necessary to investigate this,” Gibbons said. “Set up a camera or put someone there. It doesn’t seem like a hard thing to crack especially when it seems so pervasive.”

Eisenstein’s most pressing questions focus on the role played by the banks.

“Wouldn’t it be very easy for them to identify the people on the other side of these cashed checks?” he said. “Or is it that easy to set up a fake bank account, take the money out after the check clears, close the account and get away with it?”

A reporter's story

When I strolled over to the mailbox on Pavonia Avenue on April 13, I had no inkling of what had befallen Gibbons, Eisenstein and all of the others.

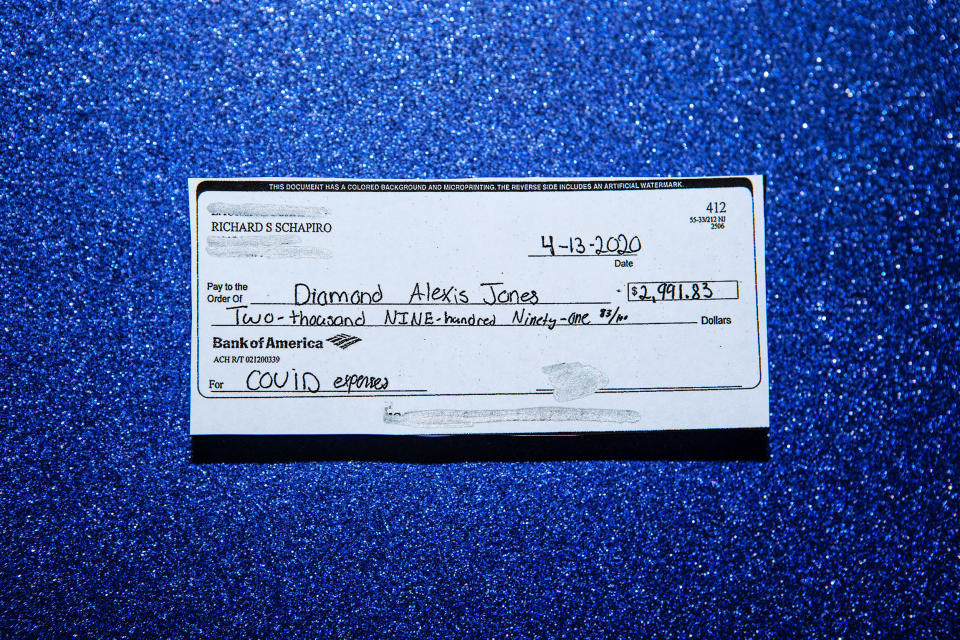

I slipped an envelope with a $2,991.83 check inside through the tiny slot and returned home. The check was for money owed to a former tenant who had just moved out of my family’s basement apartment.

The next afternoon, my wife looked up from her computer with a look of alarm on her face. “Who is Diamond Alexis Jones?” she asked.

I had no idea. That was not the name of our former tenant — not even close.

“You sent her a check for almost $3,000,” my wife said.

I cannot remember what I said at that moment, but I'm sure I rushed to her computer, face frozen, trying to get a handle on what had happened.

I had completely forgotten about the check I had dropped in the mail the day before. But it came back to me when I saw the scan of it on her screen.

The check itself looked just like the one I had sent. It had the Bank of America insignia in the middle and our bank account numbers at the bottom. But the only handwriting that matched mine was the signature.

What stood out the most was the message in the “for” line: “COVID expenses,” it read.

I immediately called my bank to report the fraud. I was told the money would be refunded, but I foolishly did not insist they freeze the account.

Three days later, a new check appeared in our online account. It was for $6,421.11 and was paid to a “Taryell" (NBC News is withholding her last name). It resembled a Bank of America check but was made to look like it belonged to a business entity with my last name: “Prosperity Schapiro LLC,” read the words at the top.

The words on the check were written in computer type except for the signature, which resembled mine but wasn’t exact.

I called the bank again and closed down the account. Once again, the money was returned.

I also filed a report by phone with the postal inspectors. I was given a claim number and told someone would follow up with me. Four months later, I’m still waiting for the follow-up.

When I reported what happened at my local police station, I found out instantly that the problem was well known to Jersey City law enforcement.

“You’re not the only one,” an officer told me. “It’s been happening a lot around here.”

He handed me a piece of paper with a phone number to call to file an official report. I did so the same day and spoke to an operator who took down the details of what happened and told me that I should expect to hear from a detective.

A few hours later, I received a call from a Jersey City police officer. After I explained what happened, she said there was no reason to file a police report if I had already filed one with the Postal Service.

“They would already be handling the investigation,” she said.

My conversations with Bank of America were more revealing. A spokesman said the first check was processed at a Bank of America, either at an ATM or through an electronic deposit. The second was processed at a PNC Bank by one of those same methods.

In the case of the first check, the spokesman said, the fraud was reported so quickly that the bank denied the transaction before the perpetrators made off with the cash. But the Bank of America spokesman said he couldn’t offer any information about the account holder or what action, if any, was being taken.

PNC Bank did not respond to requests for comment.

After I reported the thefts, none of the involved parties — the bank, the postal inspectors, Jersey City police — had given me any indication they were actively trying to track down whoever stole my checks.

So I decided to put in a little effort myself.

There are several women in the U.S. named Diamond Jones who have a middle initial that starts with the letter “A,” but there is only one person in the entire country with the first name Taryell and the last name that appeared on the stolen check, according to online record searches.

She’s 22 and lives in Florida, records show.

Before I reached out to her, I wanted to understand the possible scenarios. Could I be sure that this Taryell was a willing participant in the crime?

The answer, it turns out, is no.

“She could be a victim herself,” a former postal inspector told me.

The criminals involved in mail theft have been known to open bank accounts using stolen identities. In other cases, the crooks have passed money through accounts they gained access to without the account holders knowing. It's also possible, experts say, that the names on the altered checks were made up entirely.

After eight men were charged with bank fraud and mail theft in 2017 for allegedly pilfering mailboxes in the Bronx, then-U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara detailed the myriad ways the criminals used the banking system to turn the checks into cash.

“In various iterations of the scheme, those bank accounts have belonged to the mail thieves, to complicit account holders, or to unsuspecting third parties whose debits cards or personal identifying information has been stolen,” Bharara said at the time.

The listed phone numbers for Taryell were no good. I eventually reached her grandmother who lives in the area. She listened patiently as I described what happened to me but wasn’t able to offer much help. The grandma said Taryell had recently changed her number and she didn’t know how to get in touch with her.

“I don’t know how her name ended up on your check,” her grandmother told me, “but I’m glad you got your money back.”

Some of the victims I spoke to were given glancing details about where the checks were cashed and what, if anything, was being done to crack down on the crooks. But others said they were left almost completely in the dark.

“Banks don’t want this to get out,” said Kevin Streff, managing partner at Secure Banking Solutions, a security consulting firm based in South Dakota. “They don’t want anyone to know check fraud is happening on their watch. For $6,000, they sweep it under the rug.”

Streff said the more sophisticated thieves know that if they resist the temptation to massively inflate the amounts on the checks, they have a good chance of steering clear of the authorities and avoiding a significant response by the banks.

“With the level of regulation, law and policy now, these bad guys can stay under certain thresholds and not make it motivating to a bank to really do something about it,” he added.

The question still remained: How could thieves be plucking the mail out of the new and improved collection boxes in the first place?

The inspectors wouldn’t comment. Neither would the Postal Service.

The manufacturer of the mailboxes, the Steel Craft Corp., based in Wisconsin, referred questions to the Postal Service.

“As to the effectiveness and the performance, they’re USPS designed and built to their specifications,” said the company’s president and chief executive officer, Tom Verbos

I spoke to a handful of postal workers in my neighborhood to get their take. The majority wondered aloud whether one of their own may have gone rogue.

“With these new boxes, now it’s impossible to get mail out,” said one mail carrier who spoke on condition of anonymity out of fear of retaliation for speaking to a reporter. “Unless it’s somebody on the inside.”

Another mail carrier told me he was aware of the reports and suggested that the thief or thieves may have gotten their hands on one of the keys that unlock the blue collection boxes.

“I don’t know if someone got a hold of a key or something, but people have been complaining about this one, too,” the postal worker said at a mailbox several blocks from the one on Pavonia Avenue.

On a warm and sunny day last month, I bumped into a veteran mail carrier who has worked in Jersey City for many years. When I explained the rash of thefts, the expression on his face turned glum.

He, too, speculated that the bandits had a connection to the Postal Service.

“Personally, if I see somebody doing that, I’ll turn them in,” he said. “Because that’s my job. I want to make the Postal Service work.”

He said he’s worked there for several decades and was now in the twilight of his career.

“I want to retire with pride,” he said, “knowing the system’s going to be going on for a long time.”