Category 5 Hurricane Andrew broke 42-year lucky streak, shattered illusions of safety for Florida

In the grim accounting of tropical storms, Hurricane Andrew, a compact Category 5 storm that hit South Florida 30 years ago, sometimes gets lost.

In terms of death toll and dollar damage, Andrew can’t compare to Super Storm Sandy in 2012, or that wild hurricane year of 2017 that ended with four hurricane-name retirements (Harvey, Irma, Maria, Nate) and more than 3,000 deaths across the Southeast and the Caribbean.

Not to mention 2005, when Hurricanes Katrina, Dennis, Rita, Stan and Wilma, left behind $171 billion in damages, much of it in the submerged city of New Orleans.

Hurricane classifications: What do the categories mean?

Are you ready for hurricane season?: NHC's Ken Graham talks concerns in this video

FPL's hurricane drone: How FPL's new $1.2 million fixed-wing hurricane drone will work and what it will do

But for those of us who have lived in South Florida for a long time, Hurricane Andrew redefined hurricanes in a way that transcended the numbers.

I moved to Florida in 1984, and like most new arrivals, I was aware of the state’s reputation as a magnet for tropical storms. But the truth was, hurricanes hadn’t made a direct hit on the Florida peninsula in decades.

It was a trend that would continue during the 1980s — when year after year, hurricane season and all its dire warnings would come and go, leaving us unscathed. There were some strong hurricanes during those years, but they went elsewhere.

Hurricane Gloria in 1985 skirted North Carolina and hit Long Island, New York. Hurricane Gilbert got to Cat 5 status three years later, but it made landfall far away in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. The following year, Hurricane Hugo, a Cat 4 storm, made a direct hit on South Carolina.

Florida seemed to be charmed during those years, with the only hurricanes of note being the University of Miami football team. Florida had been so lucky for so long that in this transient state, 90% of its residents had never experienced a hurricane.

A small disturbance forms

So when an atmospheric ripple formed off the west coast of Africa during the third week of August in 1992, it was easy to be complacent.

After all, it was already an unusually quiet storm season, and would stay that way with only four named hurricanes that whole season.

It wasn’t until the middle of August that the first potential storm even appeared. Forecasters noticed a disturbance more than a thousand miles off the Lesser Antilles. Winds were 40 miles per hour, and the system was moving at 25 mph, too fast to develop much strength.

On Aug.18, forecasters were hinting at its early demise.

A news story noted that this newly named Tropical Storm Andrew “started looking more like Raggedy Andy than a potential hurricane.”

Two days later, forecasters called the storm “disorganized" as it skirted the Caribbean. But it hung in there, biding its time until a high pressure system formed, creating an atmospheric bumper that kept pushing the storm west, preventing it from bending north toward the open ocean, as so many other hurricanes had tracked.

The once-“raggedy Andy” became a tightly-wound storm, quickly growing in intensity, and moving now directly toward the Florida peninsula.

But on Friday, Aug. 21, three days before it would make landfall here, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) wasn’t issuing urgent messages.

“Just go about your normal activities this weekend,” Bob Sheets, the director of the hurricane center, said. “Don’t get all concerned at this stage.”

This was the pre-internet era, so information was less readily available, and storm forecasting wasn’t as sophisticated as it has since become.

A compact but lethal threat

The storm’s relatively small radius meant that most of the damage it created would be confined to about 35 miles from its eye. So, most of South Florida would be spared; but the part that would get hit, would get hit very hard.

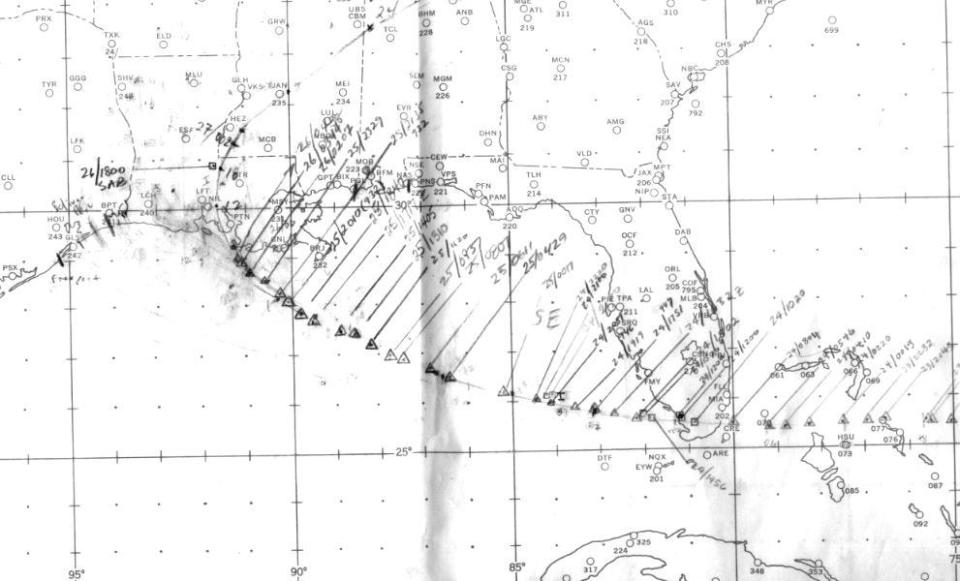

By Saturday, the NHC had put the probabilities of the landfall for this storm over an area of hundreds of miles. The odds for a Miami landfall were 23%, the chance of a West Palm Beach landfall was 20%, and a Fort Pierce landfall was put at a 16% probability. Not exactly pinpoint forecasting.

That’s because the storm was being guided by steering currents that were too random to accurately predict as it wobbled toward the coast.

One wobble here, one wobble there, and the landfall can change by a hundred miles.

The only thing that was clear was that Hurricane Andrew was going to ruin a bunch of people’s lives and spare many others. And we’d just have to wait and see who the unlucky people would be.

Meanwhile, it was also the weekend before the first day of school for Palm Beach County public schools. So, the stores were packed with shoppers standing shoulder-to-shoulder buying either hurricane supplies or school supplies. Sometimes both.

Back-to-school met back-to-Home Depot — where people began waiting for hours for new shipments of plywood to arrive by truck.

As the weekend progressed, it became evident to more people that the annual warnings of hurricane season that amounted to nothing in previous years, were going to be different this year. And that the school year wasn’t going to begin on Monday.

By that Sunday, homeowners all over South Florida were hardening their homes to the storm, digging out storm shutters that had been long forgotten. The highways became clogged with motorists packing their vehicles with household treasures and fleeing anywhere to the north. And 1,500 pregnant women checked into area hospitals, just in case.

Metrozoo in Dade County put all its flamingos in the zoo’s restrooms to keep them safe. And a wrestling match on that Sunday night between Macho Man Randy Savage and Nature Boy Ric Flair at the then-West Palm Beach Auditorium was canceled so the ring could be dismantled and the building could be used as a hurricane shelter.

A Cat 5 storm bears down

After tearing through the Bahamas, Hurricane Andrew made its Florida landfall at about 5 a.m. Monday, Aug. 24, as the strongest category storm.

It was just the third time in recorded history that a Cat 5 hurricane — one with maximum sustained winds of at least 156 miles per hour — made landfall anywhere in the United States. The most recent time this had happened was 1969, when Hurricane Camille hit the Gulf Coast at the Mississippi-Louisiana border.

Andrew blew over Elliot Key, Florida City, Homestead and parts of Kendall. It came ashore very near Florida Power & Light Co.’s Turkey Point nuclear power plant, which had shut down its reactors as a precaution.

It was impossible to measure just how strong the winds were that morning. Miles to the north, at the hurricane center’s headquarters in Coral Gables, a rooftop anemometer on the eight-story building measured a gust of 168 mphbefore it was ripped off the roof by the wind.

The storm moved at 16 mph, a fast-enough pace to leave only about an inch of rain. Unlike some other slow-moving hurricanes that stall over the land and create all sorts of flooding damage, Andrew was fast and furious as it crossed the Florida peninsula.

Its punch was delivered by the wind, often in dozens of tornadoes. And it was especially ruthless to homes built using shoddy construction practices. The agricultural communities of Homestead and Florida City were full of modest housing, trailer parks, shotgun shacks and migrant camps.

It tore through some structures as if they were made of cardboard, and sent aluminum siding through the air like surface-to-surface missiles.

Its quick path through South Florida would demolish 63,000 homes, about one out of every 10 in Dade County.

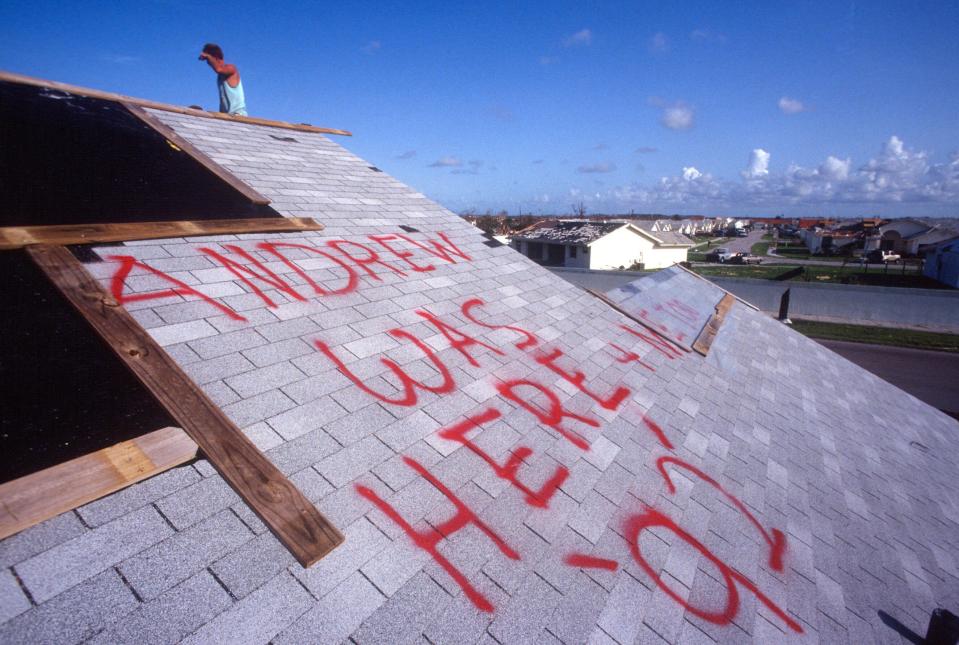

About 90% of the 1,700 homes in the community of Country Walk were severely damaged by the hurricane. Property owners there would later file lawsuits, and eventually collect against the developer of the relatively new homes for inferior construction practices, including failing to properly nail down plywood on roofs and failing to brace trusses.

Local TV stations were knocked off the air, but WTVJ-Ch. 4 weatherman Bryan Norcross stayed continued to broadcast through a simulcast with a local radio station.

Frightened people looking for advice and solace during the storm called Norcross, who advised them to crawl into their home closets and put mattresses over their heads.

A permanent change to Florida

In one respect, Andrew’s path had spared South Florida a far worse fate. A storm of that intensity hitting the heavily populated, high-rise coastlines of say, Miami Beach, Fort Lauderdale or West Palm Beach would have proven to be far deadlier and costlier.

But in another respect, the storm was a reality check — not just on the unlucky area it demolished, but on all of South Florida.

In the days after the storm, The Palm Beach Post sent photographer Greg Lovett and me to track the storm's path through South Dade County, across Everglades National Park and into Chokoloskee Island, on Florida’s Gulf Coast, where it toppled a church steeple and overturned a few trailers before it left the state.

I wasn’t prepared to experience that kind of devastation, and I had never before talked to so many people who were trying to salvage something, anything, in a pile of rubble that used to be their homes.

It was as if an invisible saw blade had removed everything — trees, power poles, buildings — over a set height. There were landscapes where nothing was taller than 10 feet, where palm trees all were lying down, as if resting. Where a car that had once been in a driveway, was a block away in the middle of the street. Where homes that had once had tile roofs, had those tiles removed as if they were nothing more than fish scales.

“What’s this?” I asked somebody about a bigger-than-usual pile of rubble.

“That used to be a bowling alley,” the person answered.

I still remember talking to Peter D’Ambrose, a bowling alley employee who foolishly thought he’d be safe by huddling under a pool table in that building.

“Everything was flying by,” he told me. “Bowling pins, pictures from the wall, whiskey bottles, chairs.”

Others talked about the sky turning green with the flashes of blown power transmitters, and about hunkering down in the shattered remains of their home after the roof was blown away.

One resident, Lester Thompson, 33, told me that he and his wife, and their two young children, fled their home during the storm as it started crumbling around them.

“I left the house because it was trying to leave me,” was how Thompson put it.

In the days after the storm had passed, the areas hit were their own unique world, unconnected from the rest of the region that carried on as if nothing had happened.

Where Hurricane Andrew had hit, there were no traffic lights, no power, and no semblance of community. Florida National Guard troopers patrolled the streets, dead animals were on the side of the road, and at night, some homeowners slept outside the rubble of their homes with loaded firearms and a posted warnings to looters.

It would take years to rebuild what was destroyed during a few short hours.

As the past 30 years have come and gone, other hurricanes have left their marks, creating more damage and more fatalities than Hurricane Andrew, which killed 15 people in Dade County and contributed to the deaths of another 15.

But Andrew has its own legacy.

It’s in the more stringent homebuilding standards it prompted in Florida, and in the migration of South Miami-Dade residents to new homes elsewhere, mostly in Broward County.

But mostly, it’s the storm that broke the spell, the storm that ended a 42-year stretch of luck that spared Florida a direct hit from a hurricane.

It was, and still is, a wake-up call to all those Floridians who had foolishly come to believe that they would always somehow find themselves outside the path of trouble.

Frank Cerabino is a columnist at The Palm Beach Post, part of the USA TODAY Florida Network. You can reach him at fcerabino@gannett.com. Help support our journalism. Subscribe today.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Hurricane Andrew made Floridians take hurricanes seriously again