'Those howls can practically knock me down': Eugene railroad quiet zone process drags on

The noise from trains blaring their horns while going through downtown Eugene can rattle windows at the Shelton McMurphy Johnson House and startle people gardening at Ya-Po-Ah Terrace Senior Apartments.

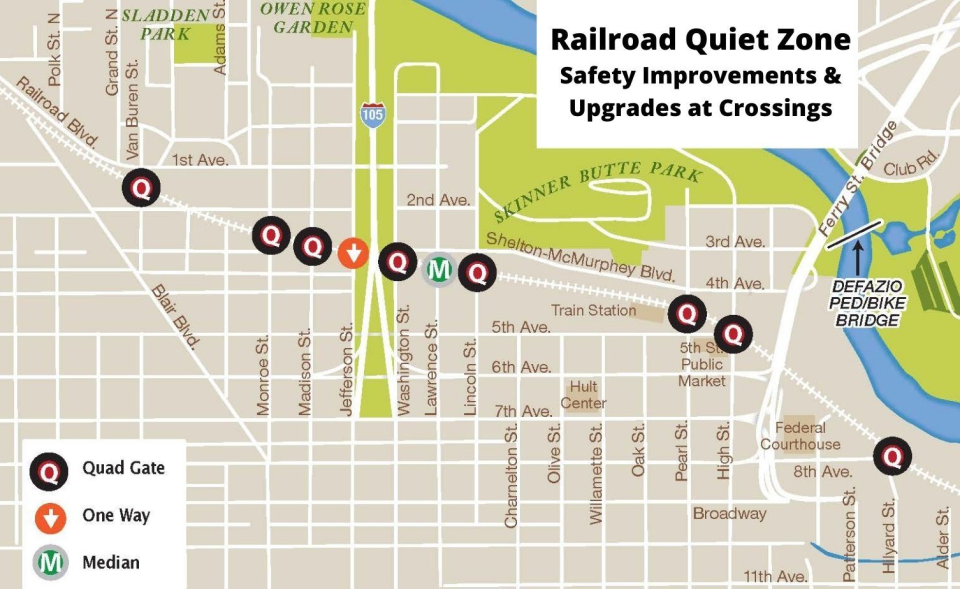

Eugene has been working since 2015 to establish a railroad quiet zone by making safety improvements at 10 railroad crossings between Hilyard and Van Buren streets, an area that spans east to west from near the University of Oregon to the heart of the Whiteaker.

Engineers sound the horn for safety reasons, but the noise is often disturbing for neighbors and businesses, many of whom are looking forward to the implementation of the quiet zone. Engineers aren’t required to sound train horns in quiet zones except in certain circumstances.

“Sometimes it wakes me up,” said Steve Myers, who lives in Ya-Po-Ah. “It’s distracting, and it’s cumulative.”

People giving tours at the Shelton McMurphy Johnson House Museum sometimes have to just stop talking in the middle of explaining something because the noise is too loud to speak over, said director Leah Murray.

The noise isn’t really an issue at Oakshire Brewing's tap house in the Whiteaker. The horn is key for safety, said founder Jeff Althouse, but it would be a good thing “if the train starts honking its horn less and nobody dies.”

City staff got the green light last year on designs for quiet zones from Union Pacific Railroad and the Oregon Department of Transportation. Progress stalled when the city and railroad couldn’t agree on permit terms.

The city recently reissued crossing order materials for review and response, Eugene Public Works spokesman Brian Richardson said. Then the process will move forward to potential permitting and, eventually, construction.

“We want this in place as soon as possible, but we have to go through the process,” Richardson said.

That process can take years as public agencies negotiate with railroads and work to meet federal standards.

Robynn Tysver, a manager in media relations for Union Pacific, said the railroad has been "actively working with Eugene on its proposed quiet zone project and helping to ensure Federal Railroad Administration standards are met.”

What's a quiet zone?

Under the federal Train Rule, engineers are required to sound the train horn 15 to 20 seconds before at-grade crossings when the train is going less than 60 miles per hour, according to the Federal Railroad Administration.

About two dozen trains pass through downtown Eugene each day, according to a city presentation. With more than a dozen crossings at grade, that's several blasts every day.

The federal rule also gives local governments the ability to mitigate effects of train horn noise by establishing quiet zones.

As of Oct. 14, there were more than 980 quiet zones across the country, according to the Federal Railroad Administration. That includes 16 in Oregon, one of which is in Westfir.

In a quiet zone, engineers don't sound the horn unless there's an emergency or they have to in order to follow other federal regulations or railroad operating rules.

Why put one in place?

Blaring horns have impacts on neighbors and businesses alike. The quiet zone likely would eliminate about 70% of the overall train horn noise throughout Eugene.

Myers, 75, moved to Eugene decades ago and has lived in Ya-Po-Ah Terrace for three years.

He had a series of concussions and is hypersensitive to sudden, loud noises. Noise from the train generally deteriorates his quality of life, Myers said.

“A lot of people say they’re used to it, but I think they just aren’t aware of how it is affecting them,” he said.

The horns are loudest in the south side of the building. It's still not ideal where Myers lives on the north side facing Skinners Butte.

“It’s bad enough for me here, but when I am visiting friends on the other side or relaxing in the garden patio outside, those howls can practically knock me down,” Myers said. “They are loud enough to feel in the body, not just to hear.”

Meyers said he has anxiety issues and is on edge when he goes to tend his raised garden bed on the apartment grounds not knowing when an engineer might blow the train horn more or for longer.

Oakshire Public House, the Whiteaker tap room of Oakshire Brewing, is within 100 yards of the train track, and the horn is “quite loud,” Althouse said.

He served on an advisory panel that met in 2015 and 2016 to make recommendations to City Council about safety features.

It wasn’t the noise that spurred Althouse to join the conversation. He got involved because there was a possibility of making Madison Street, on which the taproom is located, a dead end and that seemed “absurd.”

Althouse can understand why neighbors are irritated by the train noise but said it doesn’t impact his business and he’d rather hear the horn blare than someone killed.

“Nobody driving a train wants to hit a person,” he said. “They blow the horn loud and long, and I would too.”

The train’s impact on the Shelton McMurphy Johnson House Museum is dual in nature. The museum gets a lot of foot traffic from the Amtrak station, Murray said, but sometimes the noise “just rattles everything” in the 19th century home.

“We like the train. We like that it is here,” Murray said. “But it is loud.”

There are days when Murray doesn’t hear it, she said, but other days “it seems like it couldn’t get any louder,” and she can feel the vibrations.

The museum hosts weddings and is fundraising to put in an outside event space. Murray said she hopes that by the time that’s complete, the quiet zone is close to being in place.

“It’ll make our ability to host events more attractive because it is a concern about being able to hear,” Murray said.

What will the new crossings look like?

Local governments looking to establish a quiet zone must mitigate the increased risk caused by the absence of a horn sounding as a warning.

Project permitting and design has been ongoing, Richardson said, though plans still generally match the final crossing designs posted to the city's site.

The project will involve installing three kinds of crossings to improve safety:

Quad gates: Four gates, instead of two, in quadrants. There's little gap between the two gates on each side, meaning cars can't drive around. These will be used at Van Buren, Monroe, Madison, Washington, Lincoln, Pearl and High streets as well as at the crossing near East Eighth Avenue and Hilyard Street.

One-way: One gate comes down on a one-way road. This kind of crossing will be used at Jefferson Street, which is one way heading south between First and Fifth avenues.

Medians: One arm on each side with a median installed to prevent people from going around the gates. This kind of crossing will be used at Lawrence Street.

Designs were cleared in 2021, but the city and Union Pacific disagreed over permit terms the railroad requested related to long-term maintenance costs estimated at $250,000 a year, Richardson said.

How long has the city been working to create a quiet zone?

Eugene officials first directed staff to create a quiet zone in 2015, according to a timeline on the city's website.

The city identified funding for the project in early 2018 after a lengthy input process from a panel of residents.

Eugene City Council approved funding for the project in the spring of 2018.

In total, the city estimates the project to revamp crossings will cost $7 million-$10 million.

Construction is planned as soon as the city gets the necessary approval on designs and permits. The goal was to have the quiet zone in place sometime this year, but that's unlikely to happen.

There’s not a concrete estimate for implementing the quiet zone, Richardson said, but the city remains “committed to working through the process as quickly as we can.”

Eugene has gathered all the materials it can and put them forward, he said. Now the city is just working through the steps of the required process. Some of those steps can take months or more than a year.

Meanwhile, the noise continues to impact visitors to downtown, the Whiteaker and daily life for people like Myers who live and work near the train tracks.

“People choose to live in Eugene for the quality of life,” Myers said. "That’s a serious downside for people who live close enough to be disturbed by it."

Learn more

There's more information on railroad quiet zones in general at railroads.dot.gov/highway-rail-crossing-and-trespasser-programs/train-horn-rulequiet-zones/train-horn-rule-and-quiet.

You can find regular updates on the city's project at eugene-or.gov/2920/Railroad-Quiet-Zone.

Contact city government watchdog Megan Banta at mbanta@registerguard.com Follow her on Twitter @MeganBanta_1

This article originally appeared on Register-Guard: Quiet railroad zone timeline unclear in downtown Eugene, OR