Those just-released Florida jobless numbers? Assume they are probably baloney

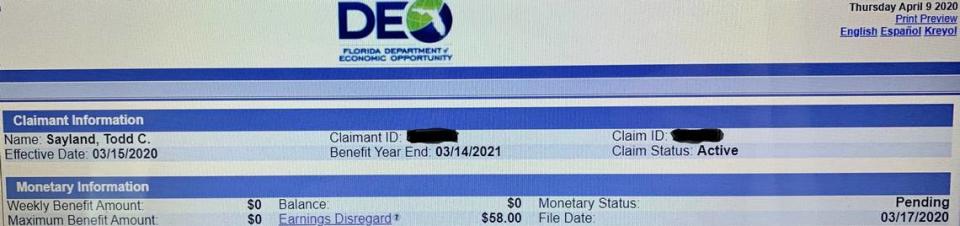

If you want to know why the latest tally of jobless claims announced Thursday is at least suspect — and probably a complete distortion of reality — consider the case of Todd Sayland.

It’s been more than three weeks since Sayland first tried to apply for unemployment benefits through Florida’s tattered online system and he’s still waiting for an answer.

The 49-year-old Fort Lauderdale waiter spent five days in a perpetual loop of entering and reentering his information. Since the system finally accepted his application on March 22, his claim has been stuck in a sort-of-purgatory ever since, his status permanently “pending.”

He checks online, he tries to call, but he’s unable to get any update on his initial claim.

“It’s ridiculous,” he said. “This system looks like it was designed to discourage you from filing.”

What’s more, he might not even count.

With so many recently unemployed Florida residents struggling to access the state’s unemployment system, managed by Florida’s Department of Economic Opportunity, it’s hard to know the true scale of job loss in the state in the wake of the coronavirus and the restaurant, nightclub and retail shutdowns that have followed.

Florida saw a decline this past week in the number of unemployment claims filed, with 169,885 claims filed through April 4, compared to 228,484 claims filed the previous week, the most in state history, according to data from the U.S. Department of Labor.

Listen to today's top stories from the Miami Herald:

Florida had the 11th most claims filed of any state this past week, but when adjusted for the size of the state’s workforce in February, before coronavirus closures took effect, Florida actually had the fourth fewest claims of any state. And when considering all claims filed over the past three weeks, as states saw their numbers swell, Florida is near the bottom when taking into account the size of the state’s workforce, according to the Labor Department data. Only five states — Wyoming, Utah, West Virginia, Colorado and South Dakota — have had fewer unemployment claims filed when adjusted for the size of their state’s workforce.

“It’s really hard to tell what the claims actually should be in Florida, because it’s so hard to get through,” said Michele Evermore, a senior policy analyst at the progressive National Employment Law Project.

Florida’s comparatively low number of claims is all the more dubious given that nearly one in seven workers in the state work in the leisure and hospitality industries, which have seen the biggest declines among any industry in the most recent federal jobs numbers. Nationally, Florida ranks fifth in the country for the percentage of its workforce in the leisure and hospitality industries, according to the most recent Labor Department statistics.

Number one on the list is Nevada, where nearly one in four workers in the state are in the leisure and hospitality industry. And Nevada is among the top states for unemployment claims when adjusted for the size of its labor market, with more than 17 percent of the state’s workforce filing unemployment claims in the past three weeks. That’s more than three times the percentage of Florida workers who filed claims in the same time period. And Nevada’s unemployment system has also struggled to meet the increased demand.

“From what I see, there continue to be a lot of people who are having trouble getting through the system in Nevada,” said Ruben Garcia, a law professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas and co-director of the university’s workplace law program. “There’s certainly technical issues that have come up, because of the volume of claims.”

Vulnerable state

Understanding the full scope of the coronavirus impact on Florida’s economy could take a while. Economists tend to see unemployment numbers as a sort of canary in the coal mine, offering early indications on the extent of economic disruption in a downturn or recession, but caution against drawing too many conclusions from the unemployment claims alone.

“Normally when we think about what’s happening in the labor market, we’re also interested in new hiring,” said Tara Sinclair, an economics professor at George Washington University. Those numbers will be factored into federal jobs reports that come later down the road, she said, and form a better basis for comparing how states are faring in the wake of the coronavirus.

Still, she says that the fact that workers like Sayland are spending days trying to file their unemployment claims gives a hint as to the state of the current job market.

“The persistence of people going and calling 500 times tells you how sure they are that there aren’t other opportunities out there for them,” Sinclair said.

While it will be some time until the true economic impact of the coronavirus is fully understood, some economists say Florida’s economy could face unique challenges.

A new study from Oxford Economics, a research group, put Florida near the top of states most vulnerable to an economic downturn because it ranks near the top among states for share of its workforce dedicated to retail and hospitality, as well as its share of elderly residents.

And Christopher McCarty, director of the University of Florida’s Bureau of Economic and Business Research, said that the coronavirus could make a dent on the number of new retirees moving down to Florida, which could further depress the state’s economy.

“People are very reluctant to take on a new obligation,” McCarty said. “All of those people from New York and New Jersey and Ohio and Canada are going to delay their moves.”

Economists say the economic impact from the coronavirus could come in multiple waves. The unemployment claims point to businesses already shuttered or scaled back, while a second wave could come from reduced spending. Restaurants, for example, are buying fewer ingredients, which in turn means farmers and other food producers are seeing a decline in revenue.

And that could apply to individuals as well. Part of the goal of unemployment insurance, and supplementary unemployment money in the federal coronavirus stimulus bills is to inject money into the economy. But problems with Florida’s unemployment system mean that even unemployed workers who have successfully filed claims are having trouble accessing the money they are owed.

The state’s Department of Economic Opportunity has taken numerous measures to try to help with the demand, adding hundreds of additional workers to help process claims, offering paper applications and rolling out a new, mobile-friendly application.

But those changes haven’t yet fixed problems faced by legions of unemployed workers across the state.

Richard Vona, a 47-year-old former waiter at Fleming’s Prime Steakhouse in Miami, successfully filed a claim on March 14, but he hasn’t been able to access any of the benefits owed to him because the system keeps crashing. He spends hours each day refreshing the website and trying to get through to someone at the Department of Economic Opportunity for an update on when he might finally get an unemployment check, with no success.

“I’ve called and recalled 15 times and gotten nowhere,” he said. “You have to think about it every day, because so far it’s been three weeks and I haven’t gotten any money.”

Miami Herald business reporter Rob Wile contributed to this report.