Thought this summer was toasty? Boise could be as hot as this Southwest city by 2100

If you thought this summer was hot, Boise, you better hope you’re not still around by 2100.

As meteorological summer ends on Sept. 1, Boise ended summer 2023 — June through August — with an average high temperature of 90.2 degrees. The city hit a high temperature of 105 degrees on three occasions this summer and surpassed the 100-degree mark on 11 occasions.

It’s not the hottest summer on record for Boise; including low temperatures, the average temperature in Boise this summer was 76.2 degrees, the eighth-hottest summer on record. But of the top 10 hottest summers in the city’s history, eight have been in the 21st century.

Now imagine this past summer’s heat, but add an average of 8.7 degrees on top of the average temperature. According to 2020 analysis from climate science organization Climate Matters, that’s the direction Boise is heading.

“I don’t have any reason to think this is a wildly outrageous sort of expectation and is probably a pretty good estimate,” Alejandro Flores, professor at Boise State University’s Department of Geosciences, told the Idaho Statesman by phone.

To put that prediction into perspective, if we add 8.7 degrees on top of the high temperature in Boise every day this summer, the city would experience 50 days at or above 100 degrees — over half of the summer. The current record for days over 100 degrees in a calendar year for Boise is 23.

By 2100, Boise’s summers will be like what Spring Valley, Nevada, experiences today. Spring Valley is a suburb about two miles outside of Las Vegas. The Las Vegas area, including Spring Valley, currently experiences an average summer high of 100.8 degrees.

Las Vegas isn’t getting any cooler, either. By 2100, Sin City will have temperatures similar to Kuwait City, the capital of Kuwait in the Persian Gulf. Kuwait City’s high over the weekend was 113 degrees.

While the year 2100 may seem like a long way off for many, the sudden temperature change will happen gradually.

By 2060, Boise will have similar summer temperatures to Chico, California. Chico is a city in northern California, about 90 miles north of Sacramento, which currently experiences an average summer high of 95.9 degrees.

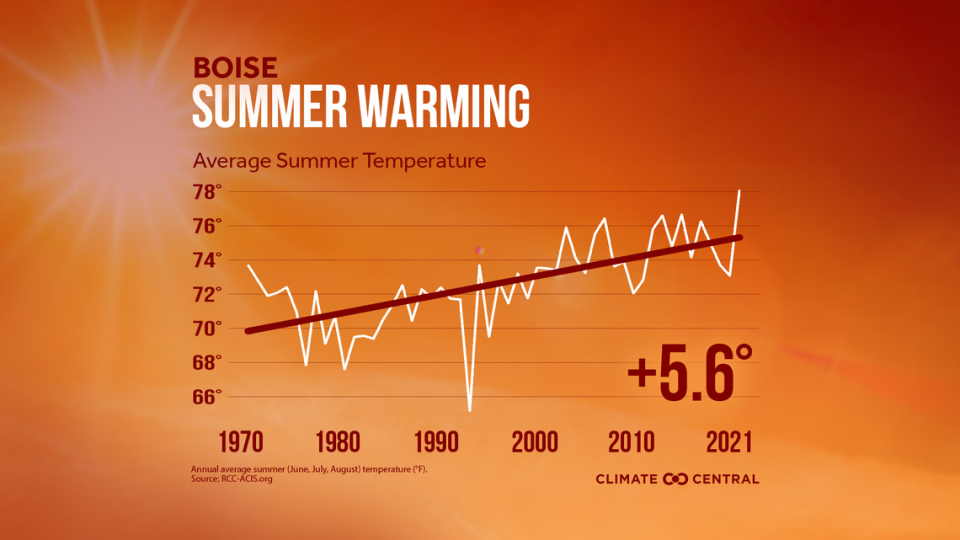

Of course, this isn’t a new phenomenon for Boise. Since 1970, the average summer temperature has risen 5.6 degrees, putting Boise on a trajectory of a 14.3-degree increase between 1970 and 2100.

What will Boise look like in 2100?

Looking out over Boise from a high vantage point, such as Table Rock or Camel’s Back, the city resembles a forest more closely than an urban metropolis. Turn around and look toward the Boise Mountains; brush-filled foothills will quickly transition into rolling hills of trees.

Among the trees is an abundance of wildlife, from small pine beetles in the foliage to larger beasts such as deer, mountain goats and bears.

By 2100, that picture of wildlife and beauty may not be so accurate anymore. Boise State’s Flores sees an ecosystem knock-on effect occurring, starting with the potential for decreased snowpack in the mountains and ending with the migration of animals.

“There are some really open-ended questions in terms of it’s warmer and we’re getting less snow,” Flores said. “But does that just mean it shifts our runoff hydrograph earlier? Or does it mean that actually, water winds up in different places?”

As things stand in 2023, snow packs in Idaho’s mountains can reach dozens of inches deep, slowly melting through the warmer months and providing water to Idaho’s reservoirs. Collected runoff water is then used as a supply for homes, businesses and farmland irrigation during the drier months of the year.

But if more precipitation falls as rain, Flores questions whether as much water will end up in rivers and streams or whether it will soak into the soil. Another potential issue he sees is more moisture being sucked back into the atmosphere — hotter temperatures hold more moisture — meaning a higher demand for carbon is required.

But the plants that produce this carbon can only do so much, Flores said.

“You can get stress on crops, where they just have to shut down and say, ‘I’m working too hard here, I’ve got to close my stemmata and sort of preserve my ability,’” Flores said. “But they can only do that for so long. So hotter summers also mean more crop stress, more potential drought, potential for more crop failure.”

It’s not just the plants that will be affected, either.

Hotter daytime temperatures will mean hotter nighttime temperatures. Many animals will look to move toward higher ground to escape the heat, such as deer, elk and bears. As they move to higher terrain, foliage and other food sources may become more scarce, resulting in a food shortage and a complete shift of the food chain.

“You can only go so high before you run out of things to be able to graze on,” Flores said. “How high will they get? Will they get so high that they start running out of quality forage and other sorts of food sources?”

Is there a way to stop Idaho’s heating?

While the future may look bleak, Flores believes that Idaho is in an excellent position to combat the effects of climate change.

“I have actually long thought that Idaho is actually in one of the better positions to be able to sort of quickly de-carbonize, and part of that is that it’s not a terribly carbon-intensive state,” Flores said.

By the term “carbon-intensive,” Flores points to neighboring states, such as Wyoming and Utah, with large fossil fuel reserves, such as coal and petroleum. For example, in 2021, Wyoming produced 239 million tons of coal, while Idaho has just one small coal-fired power plant.

This opens Idaho up to a future reliant on cleaner energy, Flores said, such as solar or wind power.

“There is this tension between needing to decarbonize quickly, but also to do so equitably in ways that you don’t assume the rural landscape is just a place where we can put whatever we need to wherever we need to,” Flores said. “But in terms of energy production, I think Idaho is actually in a pretty good place to be able to contribute to a more renewable energy future.”