Thousands of college students struggle with homelessness, housing insecurity. Why?

Fatima Turay wasn’t going to go back to college.

It’s not that she didn’t want to. College, she firmly believed, was her ticket to living her dream.

But without stable housing, was college even possible?

Turay, 22, enrolled at Columbus State Community College in August 2022 with her sights set on a future as a dental hygienist. She pushed through her classes, balancing work, studies and caring for her 2-year-old daughter, Daejore.

A self-proclaimed alpha, Turay tried to do it alone. But eventually she realized she wasn’t prepared to shoulder everything on her own, and soon after, she was evicted from her apartment.

Turay and her daughter became homeless.

Her lack of stable housing has stood in the way of her pursuing higher education more than once. She’s not alone in this struggle.

Turay is one of tens of thousands of college students who experience housing insecurity and homelessness each year in the U.S. A recent national survey found that nearly half of all college students experienced housing insecurity in 2020. In that same time, 14% of students experienced homelessness, according to The Hope Center for College, Community and Justice in Philadelphia, which conducts the annual survey.

Together, they make up a population that is underreported and often goes unnoticed on their campuses, experts say.

Every day on college campuses across the country, there are students who linger between classes and question, “Where am I going to sleep tonight?”

There are students who shower at their campus rec center and slip into an open building to find a discrete spot to tuck away for the night. Some drive around until they find an empty parking lot or a quiet street to park on while they sleep in their vehicle. Others stretch out on a friend’s couch or bunk up for a few days or weeks until they feel they’ve overstayed their welcome.

All the while, these students are trying to juggle classes, grades, jobs, internships and, in some cases, families.

“Our research shows consistently that students experience housing insecurity across all types of institutions,” said Bryce McKibben, senior director of policy at The Hope Center for College, Community and Justice at Temple University. “We have a significant problem on our hands with the numbers of students dealing with this.”

With no place of their own last fall, Turay and her daughter couch-surfed with family members for a few months while Turay tried to attend classes. It offered a place to sleep, but it didn’t help her feel less stressed about her situation.

“(My relatives) might have housing, but they’re not stable,” she said.

Turay ultimately moved back in with her former foster parents, Michelle Dranichak and Kurt Dagefoerde.

It’s a better environment for her and Daejore, but now she has different worries: Should she be working instead of going to class? How will she pay her bills and save up for an apartment? What if her parents somehow lost their home? When will things feel OK again?

With the support of her foster parents and friends, Turay enrolled for spring semester. It was a grind, she said, but it’s what she needed to do.

“I don't give myself the break. I don't,” Turay said. "Because if I'm not in school, I have my daughter all the time. ... If it's not that, I gotta be out working and find a way to get some money, ... I have to get myself on that path of being stable.”

Understanding college housing insecurity is complicated

Since 2016, The Hope Center has conducted the #RealCollege Survey, the nation’s largest annual assessment of students’ basic needs. In the 2020 survey, the most recent available data, more than 195,000 students from 130 two-year colleges and 72 four-year colleges and universities responded.

Of those students, about half of respondents at two-year colleges and two in five at four-year colleges reported they had experienced housing insecurity in the 12 months prior to the survey.

Housing insecurity includes a broad set of challenges that prevent someone from having stable or adequate living arrangements.

The most common challenges for college students, according to The Hope Center’s 2020 survey, were not being able to pay the full amount of their rent, mortgage or utility bills. It can also include going into default or collections because of housing, leaving a home because they felt unsafe or the need to move frequently.

All of these challenges affect students' ability to focus on their education, and results suggest that they are more likely to experience some form of housing insecurity than to have all their needs met during college.

While the Hope Center survey found that about 14% of all respondents said they experienced homelessness in that same time, those are likely conservative estimates, researchers said.

The survey doesn't include students who never enrolled in college, stopped out of college or attend colleges that did not field the survey, or who simply did not respond to the survey, despite being invited to do so.

Researchers wrote they were especially concerned with the 2020 survey results because they thought that the estimates were too low compared to previous years.

Students who were at the most risk of basic needs insecurity, according to the report, were much less likely to enroll in college in fall 2020, when the survey was conducted and enrollment dropped nationally by about 400,000 students. The most severe enrollment declines were among those at greatest risk of basic needs insecurity: students at two-year institutions as well as Black and Native American students, the report found.

For how many people it affects, however, housing insecurity among college students is a problem that often goes unseen.

Many college students don’t recognize that by couch-surfing, for instance, they’re considered housing insecure.

Homelessness is the most extreme form of housing insecurity, but lacking a stable place to sleep can look different for different people, said Barbara Duffield, executive director of the SchoolHouse Connection. The national nonprofit organization, based in Washington, D.C., works to overcome homelessness through education.

Duffield said there is no one-size-fits-all homelessness. While it might look like students sleeping in a shelter or on the streets, that’s not the typical case.

“Most homelessness is not outside, it's not unsheltered,” Duffield said. “It's staying temporarily with other people because there's nowhere else to go.”

The Hope Center found in 2020 that 1% of students surveyed at both two-year and four-year colleges, fewer than 300 students, were sleeping outdoors, like at a bus stop or on the sidewalk, and 1% of two-year college students reported sleeping at a shelter in the previous 12 months.

Meanwhile, 10% of two-year students and 11% of four-year students reported that they were temporarily staying with a friend, relative or couch-surfing until they could find more-permanent housing.

“I think part of the misconception is that that's somehow not homeless, that it’s somehow not vulnerable,” Duffield said.

That societal stereotype of what homelessness is “supposed” to look like is why some students don’t realize they’re actually experiencing housing insecurity, Duffield said. The stigma that poverty is somehow OK when you're in college can be a barrier, she said.

“They think, 'Well, I have a roof over my head.’ So they're not really homeless, that it's a lesser form of homelessness,” she said. “... The language does pose a barrier to services, for sure.”

Jennifer Erb-Downward, director of housing stability programs and policy initiatives at the University of Michigan’s Poverty Solutions, agreed.

"Everybody wants to feel like they have control in the situation. No one wants to identify as homeless," she said. "You are not going to find out how many college students are experiencing homelessness by asking whether or not people are homeless. You would find out by asking about their (individual) living situation."

Are you living in your car? Are you frequently moving from place to place? Were you forced to leave your apartment because you couldn’t pay rent? Questions like these, Erb-Downward said, can better help researchers collect better data, but also help students get the resources they need.

Even for students who do recognize their housing insecurity, their plight is often under recorded. That’s because college students are an understudied population in the realm of housing insecurity research.

“There is almost nothing about college,” said Erb-Downward of the data about college housing insecurity.

Erb-Downward studies and advocates for families, K-12 students and young children experiencing homelessness. There is far more research happening in that space, she said, because it is required by law.

Passed in 1987, the McKinney–Vento Homeless Assistance Act is a federal law created to support the enrollment and education of homeless students. Its purpose is to ensure that all children, from preschool through high school, have equal access to a public education as non-homeless youth.

Erb-Downward said McKinney-Vento requires schools to identify students experiencing homelessness, meaning there is a plethora of local and national data about K-12 youth. There is no analogous program, however, for college students struggling with homelessness.

McKibben said it’s taken time for leaders at the higher education level to recognize that college students need the same attention to basic-needs security that K-12 students do.

“There were people who said, ‘Well, they’re basically adults,’” he said. “They didn’t see the role for policy or systemic change.”

While there are a few organizations like the Hope Center and Schoolhouse Connection conducting annual surveys to identify these students, Erb-Downward said there is no universal data collection for this population. Because many students experiencing housing insecurity don't make it to graduation or put their studies on hold, it’s also difficult for researchers to reliably track the prevalence of the issue.

“There's nothing even close to really trying to tackle this question of how many college youth are experiencing housing instability and homelessness and what that looks like,” she said.

'Trying to balance everything is not easy'

Turay has big dreams.

She wants to be a dental hygienist and open up dentistry clinics in her home country of Sierra Leone. She wants to be the “it girl” for fitting veneers. And she wants to create a life where her 2-year-old daughter Daejore never wants for anything.

All of those dreams have the same common denominator: a college degree.

“I got dreams, and I got stuff I want to do in life,” she said. “And it all ties into I gotta go to school to go get it. Because if you want to be real in America, you gotta have a job and you gotta go to school. You got to take care of that, in order, to really do what you really want to do.”

Thus far, the journey to that American dream has been rocky, Turay said.

She moved to the United States with her family when she was 3 years old to escape civil war in Sierra Leone on the southwest coast of West Africa. She spent her childhood bouncing between living with her grandmother, foster parents and group homes.

By the time she aged out of the foster care system at 18, Turay said her life took a sharp turn. She had plans to attend Central State University, Ohio’s only public historically Black university, but she could not enroll without a high school diploma.

She met a guy who introduced her to drugs and a life on the streets.

“I was just being reckless, like, not even really caring about my responsibilities,” Turay said.

She lived that life for two years before finding her way to rehab. Something, Turay thought, had to change.

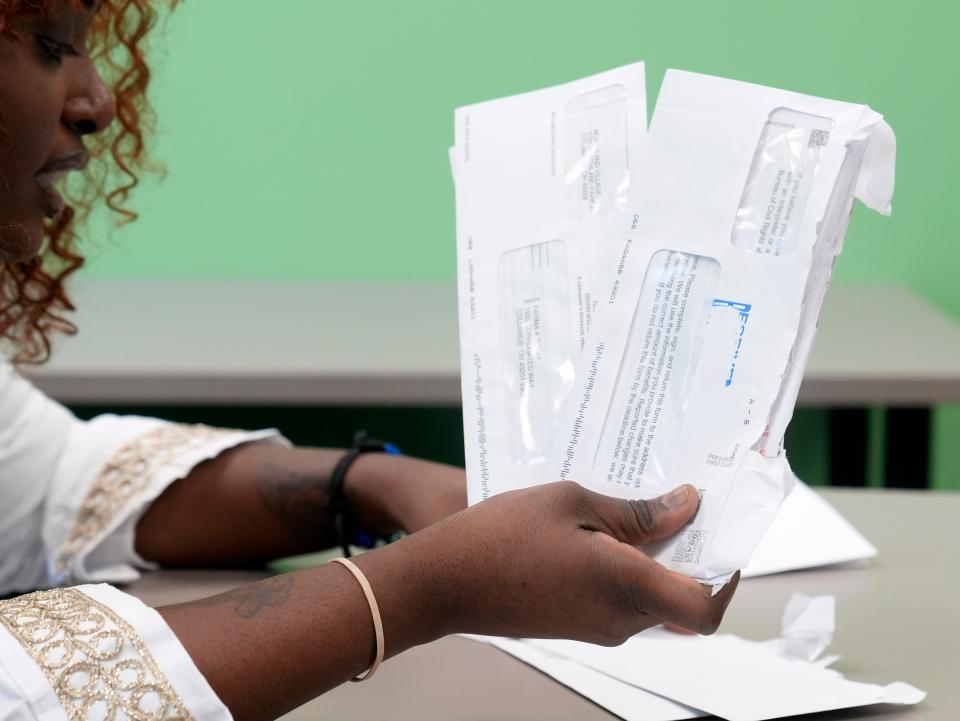

While in rehab, she graduated from Westwood Preparatory Academy with her GED diploma. And she met Jill Gorz, clinical services manager at Star House.

A guiding Star

Star House is the nation’s only 24/7 drop-in center for youth ages 14-24 experiencing homelessness. The Columbus nonprofit group also operates the only housing village of its kind in Greater Columbus for college-age youth who are exiting homelessness.

Founded in 2006 as a research project through Ohio State University, Star House was originally located in an 1,800-square-foot house in the University District. Star House served 400 youths that first year, offering everything from bus passes and a hot meal to clean clothes and a few hours of respite.

Almost two decades later, Star House now runs independently out of a 14,000-square-foot former warehouse in the Milo Grogan neighborhood. As a 24/7 drop-in center, young people experiencing homelessness have immediate access to safety, basic needs and stabilizing resources.

Gorz said Star House serves about 100 different youths each day. In 2022, the center served 1,100 young adults. The majority are 18 or older, and many did not finish high school. A handful of Star House clients try to attend college each year, Gorz said, but it’s not easy.

“It’s really challenging to do college when Star House is your only housing,” she said.

Most colleges and employers require a stable address to apply. It’s a catch-22 situation: They can't find a place to live until they get a job, but can't get a job until they find a place to live.

There are also rules that prevent many full-time students from leasing some Low-Income Housing Tax Credit properties and using Section 8 housing assistance, McKibben said.

Star House tries to be a good home base for young adults trying to go to college, Gorz said, but there are other variables. Securing financial aid and reliable transportation, doing class assignments on their phones, even finding somewhere to store your personal belongings when you’re in class can be taxing.

“No one wants to go to class with all their stuff,” she said. “It’s like wearing a big ‘I am homeless’ sign.”

College is on the radar for a lot of Star House's clientele. It can be a challenge, Gorz said.

“Surviving takes up a lot of their mental energy,” she said. “If they’re able to get housing, then they’re usually pretty successful.”

That’s what happened for Turay.

Turay got hooked up with Star House in 2019. It gave her shelter and safety from her ex-boyfriend, she said, but it also helped her find her footing.

Gorz helped Turay get into her first apartment on the city’s East Side, and taught her how to budget, fill out applications and understand security deposits. That first apartment changed everything, Turay said. She had stability, security and hope.

Enough to convince her to give college another chance.

'A whole lot of potential'

Turay got serious again about her education after her daughter was born. She didn’t feel prepared for this new stage of her life. School, she said, would make everything alright.

She’s doing it now with the support of her foster parents, Dranichak and Dagefoerde.

“Their thing is to keep pushing me to do what I say I would do,” Turay said. “They see a whole lot of potential in me.”

It’s been a lot to manage, Turay said, between going to classes, getting her daughter to day care, finding stable housing and working part-time as a cocktail waitress at Hollywood Casino.

She doesn’t have a laptop right now, so she sticks around after class to use the computers in Columbus State’s library. Without a driver’s license, Turay relies on Dranichak to drive her to class and work. She’s often on her own to find a ride home at the end of the day. That usually means she's navigating the COTA bus schedule.

Turay doesn’t like having to depend on others, but she appreciates her foster parents' support.

“Trying to balance everything is not easy,” she said.

When things get hard, Turay remembers her biggest motivation: Her little girl.

“When I had my daughter, I was not prepared at all. All I kept thinking about was going to school and school was going to make it right,” she said.

“I want her to look at me and she’s like, ‘This is my mommy. When she wants something, she goes and gets it. She is my mommy who made all her dreams come true. She's my mommy and she’s doing her thing.’”

Some students make it through. For others, their dreams are deferred.

College is possible for homeless and housing insecure students.

Gorz has seen it herself.

“It does happen,” she said. “But they just need the mental space to make it happen.”

That’s where policymakers can make a difference.

McKibben, with The Hope Center, said there are “so many different levers” to adjust in addressing student housing insecurity.

Making college more affordable through federal and state investments, expanding access to financial aid options, and changing the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s qualifications for low-income housing to include college students would all help fill that gap, he said.

Some of those levers are starting to move.

In April, the U.S. Department of Education changed some of the questions on the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, better known as FAFSA, to make it easier for homeless youths to apply for financial aid.

U.S. Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio), former Sen. Rob Portman (R-Ohio) and Sen. Angus King (I-Maine) introduced the Housing for Homeless Students Act of 2022 in November, which would update current law to extend the low-income tax credit, making it so housing-insecure and homeless college students, including veterans, can access affordable housing while pursuing an education. The bill is currently in committee.

But there’s still a long way to go, said Duffield of Schoolhouse Connection.

“If nothing changes … that road to self-sufficiency, economic independence and stable housing through higher income is essentially blocked,” she said. “We'll have a group of people who are essentially shut out of the middle class. Shut out of economic opportunities. Children will continue to struggle with poverty and the intergenerational effects of poverty.”

As for Turay, she’s now working full-time at the casino as a cocktail waitress, and she just moved into a new apartment for her and Dajore. Dranichak still helps out by giving her rides, and Turay is working toward getting her driver’s license again.

School, however, will have to wait for the time being.

She stopped going to classes mid-way through the spring semester at Columbus State to focus on earning money and getting into an apartment.

Some of her dreams are on hold, just for now.

Reporters Megan Henry and Michael Lee contributed to this reporting.

This reporting was made possible through funding from the Education Writers Association.

Sheridan Hendrix is a higher education reporter for The Columbus Dispatch. Sign up for Extra Credit, The Dispatch's education newsletter, here. Email her at shendrix@dispatch.com. Follow her on Twitter at @sheridan120.

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Thousands of college students struggling with housing insecurity. Why?