Thousands of Detroit flood victims still waiting for aid 9 months later

Financial help from the government may never materialize for some Detroit victims of last summer's devastating flooding while thousands of others already have been denied recovery aid.

Federal data shows that nearly 39,000 households in the city had gotten some money from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) as of March 1 for flood damage. But another 8,204 families are still waiting and 14,163 have been denied.

In addition, there’s been no action on more than 40,000 separate damage claims filed with the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department or the Great Lakes Water Authority, as both agencies await the final investigation of backups in sewer systems that caused widespread flooding in mostly east-side neighborhoods after historic rainfalls. DWSD has already predicted most claims will be denied because initial findings blame heavy rain as the main cause, despite power failures at key east-side pumping stations.

That has left many Detroiters frustrated with limited options, including using their own savings to pay for repairs to basements and appliances or going to nonprofits for help.

Debra Lowe was denied a grant from FEMA in September after more than $38,500 in damage at her east-side home. Her insurance company paid her $14,176, less than half of what she needed for repairs.

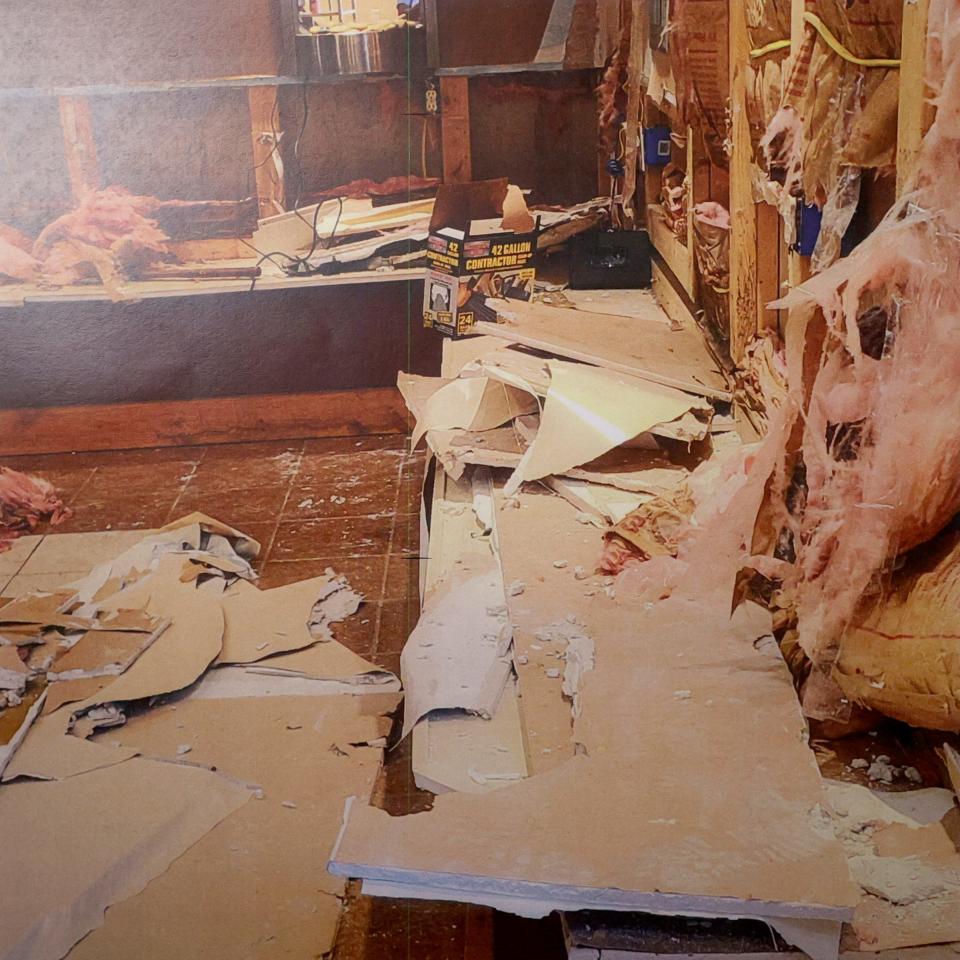

Lowe's softly lit basement is adorned with tables, speakers and mirrors for ballroom dancing practice and includes a kitchen. The flood ruined her cabinets and appliances and much of the drywall needed to be torn out.

“I’ve gotten back to normal now, but it really had me down for a while," Lowe said. "This is the third (flood). I was really frustrated. I got kind of depressed for a while.”

In a denial letter to Lowe, FEMA said because her home was covered by flood insurance, she was not eligible for federal relief funds. The letter said she could appeal.

“I appealed it and my appeal was denied. I put in a claim with the city of Detroit and the Great Lakes Water (Authority). I have not heard a response,” said Lowe, who spent about $10,000 on a new sump pump and backflow preventer to reduce the chance of future floods.

FEMA has granted more than 56,000 claims in Wayne, Oakland, Macomb and Washtenaw counties, paying out more than $188 million as of this month, according to the agency.

Another 22,700 claims have been deemed ineligible for help and another 14,000 are still awaiting a decision, the majority in Detroit.

After a 2014 flood, more than one-third — about 44,000 — claims were found ineligible. The current denial rate so far is lower. FEMA has found about 27% of claims ineligible in the four-county disaster area as of last month, without factoring in the pending cases.

Although some residents hope to go to court for relief, lawsuits filed against government entities like GLWA will likely take years.

Attorney David Dubin, who has sued multiple cities over floods during his 23-year career, said he has never received so many complaints of FEMA denials regarding a flood.

More than 3,000 metro Detroiters contacted him about not receiving federal assistance for June flood damage. He called the denials a “human rights issue” because damages involved necessities such as needing a new furnace during colder months.

“I never heard this level of complaints of not being able to get the FEMA grant money and having to jump through all the hoops like people are now, which leads me to believe something has changed,” Dubin said.

“People were having to file an appeal to get their money. It appeared from those conversations it was a routine process of denying right off the bat. If you make people appeal, you’re going to reduce the people because they’re frustrated, throw up their hands and walk away.”

FEMA spokesman Cassie Ringsdorf told the Free Press the agency's goal is to help those who don't have insurance or are underinsured with "necessary expenses and serious needs."

"The assistance is meant to return a home to a safe, sanitary and functional residence," Ringsdorf wrote in an email. "Federal assistance cannot duplicate the benefits provided by other sources, such as insurance, and cannot pay for all losses caused by a disaster.

"As the long-term recovery continues there, we’re committed to supporting those efforts and working with applicants to ensure they receive the federal assistance they are eligible for."

More: GLWA staff believed disabled pump station could handle rain that caused massive flooding

Detroiters Marjorie and Thomas Dickerson did not receive a FEMA grant but qualified for a loan of more than $20,000 through the U.S. Small Business Administration, which partners with FEMA to provide disaster recovery loans.

The Dickersons were told to fill out paperwork for a grant but struggled to get answers about qualifying for one. Ultimately, they ended up applying for and taking a loan instead because they were desperate, Marjorie Dickerson said.

“What does it take to qualify for a grant? I’m a senior citizen. I’m not making more money. I’ve sunk my life savings into this home. I never have asked for any money before. No welfare, no nothing. And when I need help, I’m given a loan. It’s kind of disheartening,” she said. “I worked to have this dream. It’s not much but it’s mine.”

Their basement in the Aviation Sub neighborhood on the city's west side collected up to 6 inches of water in some areas and they had to throw out large items like a mattress and sofa bed.

Dan Shulman, spokesman for FEMA Region 5, said individuals are sometimes referred to the SBA based on their income. SBA spokeswoman Laura Castro Lindarte told the Free Press that the agency does not publicly share information on the income threshold. FEMA does not discuss individual cases because of federal privacy laws.

Shulman added that there is no fee or impact to people's credit if they apply for the SBA loan. Those who take a loan will typically be required to pay it back with a 1%-2% interest rate over up to a 30-year period.

Detroit City Council President Mary Sheffield, in a statement, said the city must do more to make sure Detroiters have access to aid.

“There have been several studies and articles published on the racial disparities that exist in Black and Brown communities with respect to accessing disaster relief funds from FEMA. Often times the process is slower and fails to properly disseminate information in communities of color. In Detroit, this disparate treatment rang true with the response to the recent flooding,” Sheffield said.

(This article was produced in partnership with Outlier Media, a news organization that runs a text messaging service to share critical information with Detroiters. Text "Detroit" to 67485 for information and resources.)

Low expectations for help

Some residents didn't even bother to apply, saying they knew the process would be fruitless and frustrating.

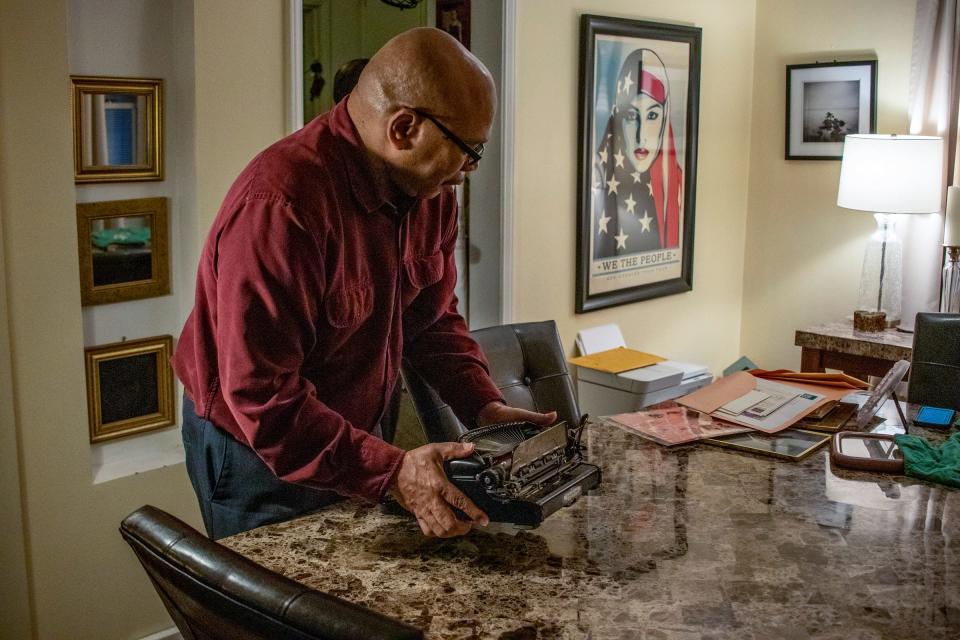

That includes Frank McGhee and his wife after they saw denials in their Moross-Morang neighborhood and doing research.

“We looked at the FEMA application and we read through reports and realized most people were being blown off by this. They’re not getting the help they’re supposed to get. I said to my wife, ‘We better just forgo the application altogether and keep what we got as best as we could,’ ” McGhee said.

McGhee had nearly 8 inches of water in his basement and remembers watching a “river” flow on his street. He said it took a whole day to get everything removed from his home.

“Luckily, our photographs from our wedding were not down there,” McGhee said. “But a lot of things that we kept over the years … were all destroyed. Everything I had from those wonderful memories was destroyed. I was just so devastated by what happened, and so was my wife, but we did the best we could.”

To pull through, McGhee spent more than $3,500 of his savings on a new water heater, washer and dryer. Work still remains to fix his water-damaged walls.

“It was as if we were abandoned,” McGhee said. “We wonder, who's getting the short end of the stick here? Detroiters?”

Some like Jacqueline Richmond, who decided not to file any claims, continue to live without crucial fixtures in their homes.

“I didn’t want the headache,” said Richmond, who lives in the Jefferson Chalmers neighborhood, explaining why she didn’t file a claim with any government agency. “(Filing) was worth it, but I was just trying to get my basement cleaned out, and they have a deadline. I’m here by myself, I don’t have anybody or any children. (Cleaning the basement) was my main concern and I was just drained — physically and mentally.”

Since the flood, Richmond has been living without a washer and dryer in her home. After replacing her hot water tank, a tub and snowblower — not to mention repairs to her flood-damaged car — her emergency fund is nearly drained.

“All I could do was pray,” said Richmond, 61. During the storm, her entire basement flooded to the top step of the stairs, just shy of the landing. She has lived in her colonial home on Piper Boulevard since she was a child.

She lost many heirlooms, including her late father’s collection of tools that earned him the title of neighborhood handyman and the most heartbreaking loss: her family’s Christmas tree topper — a Black angel that had been in her family for more than four decades.

“You name it, we lost it,” she said.

Richmond now has shelves in her basement, leaving nothing of value on the floor.

Nonprofits step in while claims in limbo

A final report detailing an investigation into the June flood is expected in April or May, GLWA officials said. But that likely won't mean much for flood victims.

DWSD predicts most of the nearly 20,000 claims it received will likely be denied because preliminary engineering studies have found that the significant volume of rainfall was the leading cause of flooding and subsequent basement backups — not defects in the system.

Under Michigan law, the city can be held responsible if there was a sewer defect — it knew about or should have known about — that it didn't fix and was 50% or more at fault for the flooding.

In addition to the DWSD claims, none of the approximately 24,000 claims filed with GLWA across metro Detroit, including about 3,900 claims filed by Detroit residents, have been resolved. GLWA and DWSD estimate that responses are expected in May. GLWA hasn't commented on what will happen to claims it has received, saying the final investigation is pending.

Nonprofits have stepped in to help fill the need for repairs.

Josh Elling, CEO of Jefferson East Inc., said his group has spent approximately $700,000 — a combination of grant money from the Michigan State Housing and Development Authority Neighborhood Enhancement Program and A.A. Van Elslander Foundation — in disaster recovery work, including home repair grants, appliance replacements and staffing.

The association represents the neighborhoods along the east Jefferson Avenue corridor, a portion of the city that was severely impacted by the summer flood.

The organization still receives hundreds of calls per week to its neighborhood resource hub line, mostly for furnace repairs and replacement, and continues to deal with a bottleneck of basements in need of sanitizing and mold remediation.

“Part of the challenge is that this wasn't just a flood, this was a flood combined with folks that are really economically challenged, sort of multigenerational concentrated poverty, and then layer a natural disaster on top,” Elling said. “It's all of the challenges we face in helping residents navigate home repair resources exacerbated by a natural disaster. So it's going to take a while to recover from that."

Another group operating in a similar vein, the Eastside Community Network, said there is frustration among residents in the city’s flood-prone areas who have suffered through multiple events with little change. Thanks to a grant from the Kresge Foundation, ECN was able to replace 30 hot water tanks in addition to facilitating applications for financial assistance.

“I just think there's anger at a system that routinely does this,” said Donna Givens Davidson, president and CEO of ECN. “Why haven’t we increased the capacity of our pumping stations? And why is the city of Detroit continuing to approve projects that remove permeable surfaces and replace them with impermeable surfaces?”

This perceived lack of change signals a lack of investment in residents, Davidson said, contributing to the historic displacement of Black Detroiters. Elling said volunteers encountered about two dozen families who abandoned their homes and moved to apartments in the suburbs because they couldn’t get resources for crucial repairs.

“I think right now people are feeling pretty lost, pretty abandoned, and upset,” Elling said, “and we've got to do something to get a handle on this because it's going to start raining again pretty soon. And if we go through this again, I don't know if residents can handle another disaster like this.”

What’s being done for the future?

Money is flowing in to improve system infrastructure and reduce the chance of future problems, officials say.

In May, DWSD will begin a five-year $40 million project to expand stormwater capacity in the Far West Detroit neighborhood. The project aims to open 99 million gallons of stormwater capacity in the regional sewer system by disconnecting downspouts and diverting stormwater to two new detention basins in Rouge Park.

Michigan is set to receive $86 million through federal grants for flood recovery, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development announced March 22, with $57.6 million to be directed to Detroit.

Though plans for how the city intends to spend the money have yet to be determined, the funding will go toward recovery from the June flood, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. A portion will be used to expand a new program intended to help protect Detroiters’ basements from future flooding, said Gary Brown, director of DWSD. Officials are analyzing specific eligible uses for the funds.

The program will target 11 neighborhoods that have faced backups during severe storms, beginning with Aviation Sub and Victoria Park where 530 households are expected to be serviced with new backwater valves and sump pumps. Brown said he encourages homeowners to apply and use the city’s new flooding and basement backup handbook.

But residents who already paid to retrofit their own basements with backflow preventers are now frustrated.

Residents like Lowe and the Dickersons paid thousands for new mitigation systems before the program launched.

“We’ve already spent the $7,500,” said Marjorie Dickerson. "After spending all that money, can I get reimbursed?"

In February, she unsuccessfully pushed the mayor’s office at the city’s Basement Backup Protection program news conference to reimburse her and others. The city says residents in these positions are out of luck.

The federal funding "will not allow for previously installed equipment at residential properties. The work was not performed through a contract with established pricing with licensed plumbers. There is no funding source currently that would allow for reimbursement of flood mitigation measures on private property," DWSD spokesman Bryan Peckinpaugh said in an email.

In May, the city — through vendor American Water — is set to begin offering a service and sewer line warranty program for about $8 a month, Brown said.

“If your basement backs up because your sewer line is blocked, they’ll clean it. If your sewer (or service) line is broken, they’ll replace it,” Brown said.

GLWA has approved its capital improvement plan for fiscal years 2023-27 that details $1.73 billion in total spending, including $126 million allotted for upgrades to the Freud and Conner Creek pump stations. Electrical shortfalls at these facilities caused a delay in pumping and the outright failure of several pumps. However, even without these power issues, significant damages would have still occurred, according to consultants.

On Tuesday, the authority unveiled power supply upgrades to the Freud and Blue Hill pumping stations on the city's east side. The pumping stations installed five transformers, each connected to independent lines, and the power supply was converted to DTE Energy. During the June rainstorm, a damaged wire limited the number of pumps operating at Freud and contributed to the severity of the flooding.

"I'm hoping 2021 was an anomaly, but we're preparing if it wasn't," said Suzanne Coffey, interim CEO of GLWA. "I don't want to give you the impression that somehow we can now all of a sudden handle 8 inches of rain in a day, the systems can't handle that, the pipes are the primary bottleneck for that."

GLWA also announced the installation of monitoring systems that provide power quality diagnostics at the Conner, Freud and Blue Hill pumping stations. Further, the authority said it has reinspected approximately 25 miles of the regional system — accounting for about 13% of its sewer system —in the months after the summer flood.

Despite supposed progress and promises of further improvements, Richmond said she won’t feel completely safe in her home until a major upheaval of the city’s water system is undertaken.

“Until they fix the infrastructure of our old piping system and water system, this is going to continue to happen,” she said. “You can only put so many Band-Aids on and after that you gotta start doing major surgery."

Dana Afana is the Detroit city hall reporter for the Free Press. Contact Dana: dafana@freepress.com or 313-635-3491. Follow her on Twitter: @DanaAfana.

Miriam Marini is a breaking news reporter for the Detroit Free Press and Outlier Media. Contact Miriam: mmarini@freepress.com or miriam@outliermedia.org.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Detroit flood victims still waiting for aid 9 months later