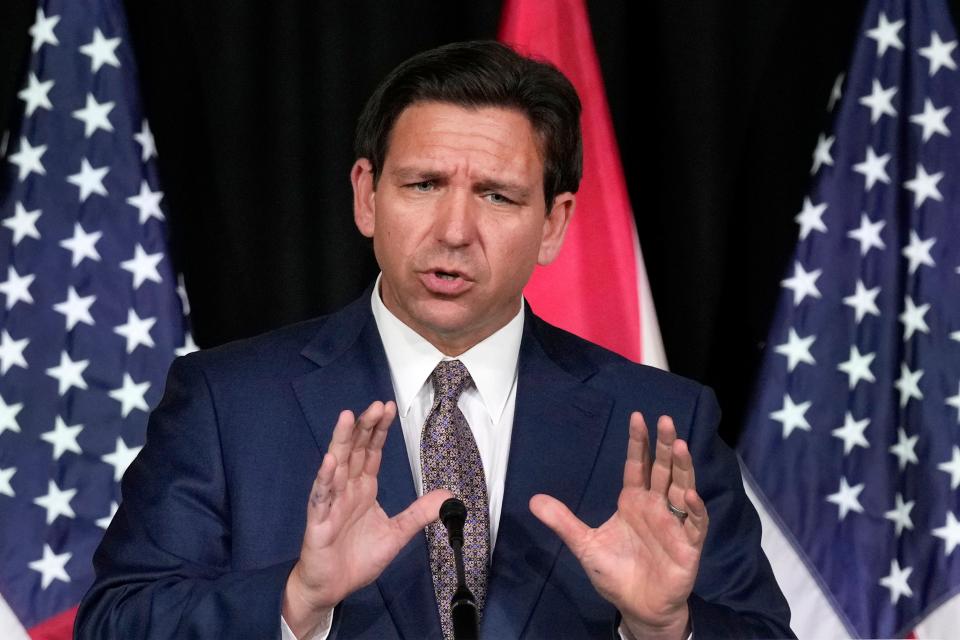

A threat to free speech: Ron DeSantis targets journalists, media with new legislation

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

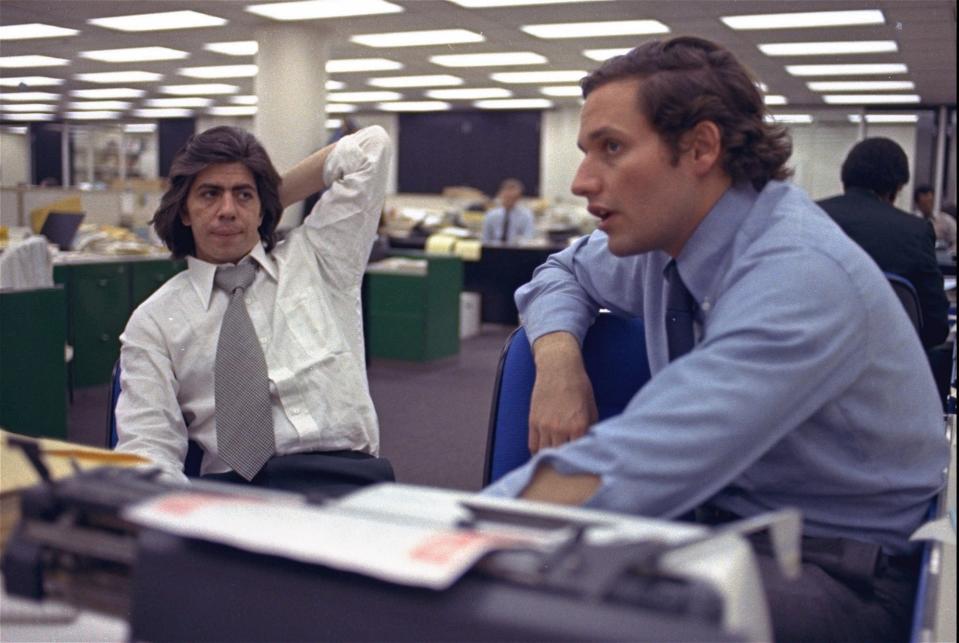

Could President Richard Nixon have sued Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein for exposing the Watergate scandal? Could Sen. Strom Thurmond have sued the NAACP for criticizing his opposition to civil rights laws as racially discriminatory? Could former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton have sued Rush Limbaugh for joking that she once propositioned him in an elevator?

The questions may seem ridiculous in a country that values a free press and free speech, but a proposed new law in Florida, backed by Gov. Ron DeSantis, seeks to radically change the defamation protections that the Supreme Court afforded journalists – and everyone – in a landmark decision nearly 60 years ago.

Legislation would make it easier for politicians to sue for defamation

Under the bill, HB 991, public figures would no longer have to meet a heightened standard to prove defamation if the statement “does not relate to the reason for his or her public status,” making it easier for politicians to sue when allegations of infidelity or even of crimes committed before their assumption of office surface.

Opinions in your inbox: Get exclusive access to our columnists and the best of our columns

But the legislation doesn’t stop there. Under the proposed law, any allegation that someone has discriminated against another person or group because of their race, sex, sexual orientation or gender identity would constitute defamation per se – making it far easier to subject the speaker to huge penalties.

HB 991 would do even more to make it easier to hold someone liable for defamation – defined as a false statement about another person that causes reputational damage. Currently, people whose statements are found to be defamatory have to pay damages to those who are harmed.

But the Supreme Court has long recognized that free speech must have a necessary amount of “breathing space” to survive. That is why, in the landmark 1964 case New York Times v. Sullivan, the court decided that when people are discussing public figures or matters of public concern, a higher standard for finding liability must be met.

People are only liable for making false statements when talking about politicians or other public figures if the plaintiff can prove that the speaker knew or should have known the statement was false.

This means people can’t be sued for their opinions, mistakes and misstatements. We can argue and debate about politics without being hauled into court to prove that every word we spoke was correct.

It also means that reporters and news organizations are free to report on breaking news, government corruption scandals, emerging legislation and the implementation of new policies without fear that the politicians they’re covering will sue them for harming their reputations.

Will your state be next?: A school choice revolution is storming the country this year

Is social media the new Marlboro Man?: Big Tobacco settlement holds lesson for Big Tech.

Information from anonymous sources would be considered false

This new bill, however, would declare statements made by anonymous sources presumptively false. And it would remove journalists’ right to refuse to reveal confidential sources.

The result: If Woodward and Bernstein refused to identify the source of their Watergate reporting, as in fact they did, for more than 30 years, President Nixon could have sued for defamation and the fact that their stories were true might not have mattered.

It’s worth remembering the facts of Sullivan to understand where the consequences of this bill would be felt the most. In Sullivan, an elected official in Alabama sued The Times, as well as four Black clergymen, for publishing an advertisement placed in The Times by the clergymen and other civil rights activists. The ad described police violence against civil rights activists in Alabama, criticized the police and asked readers for support.

The circumstances are eerily similar to current events. Around the country, policymakers are banning instruction on race, equity, inclusion, sexual orientation and gender identity. With this legislation, Florida politicians seek to insulate themselves from criticism and weaponize the courts to chill speech.

What is Section 230? How two Supreme Court cases could break the internet as we know it.

Need a college degree for an entry-level job?: Blame the Supreme Court

The effort flies in the face of what the Supreme Court has called “a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.” It’s un-American.

That’s doubly pernicious given the bill’s insistence that allegations of discrimination automatically count as defamation. Organizations such as PEN America and many others have criticized recent policies and decisions made by lawmakers in Florida, including the Stop WOKE Act, numerous educational gag orders and books bans as discriminatory and as disproportionately affecting people of color and people who identify as LGBTQ+.

Those criticisms are based on thorough evaluations of the content of the books and curriculum targeted in the laws, which unmistakably zero in on narratives and authors of these identities.

Opinion alerts: Get columns from your favorite columnists + expert analysis on top issues, delivered straight to your device through the USA TODAY app. Don't have the app? Download it for free from your app store.

Now, each of these organizations – along with thousands of ordinary people who spoke out against these laws – could be exposed to lawsuits simply for raising fact-based claims about the censorious nature of these policies.

Make no mistake: HR 991 is blatantly unconstitutional, but that doesn’t mean it can be ignored. At least two Supreme Court justices have said they’re willing to consider rewriting laws protecting freedom of the press.

More important, it’s a chilling sign that some politicians aren’t content to enact discriminatory and censorious laws. They want the power to silence their critics. We must stop them from seizing that power before it’s too late.

Kate Ruane is director of U.S. Free Expression Programs at PEN America.

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: DeSantis threatens free speech protections with new defamation bill