What the three-fifths clause tells us about strokes and other health disparities for Black Americans

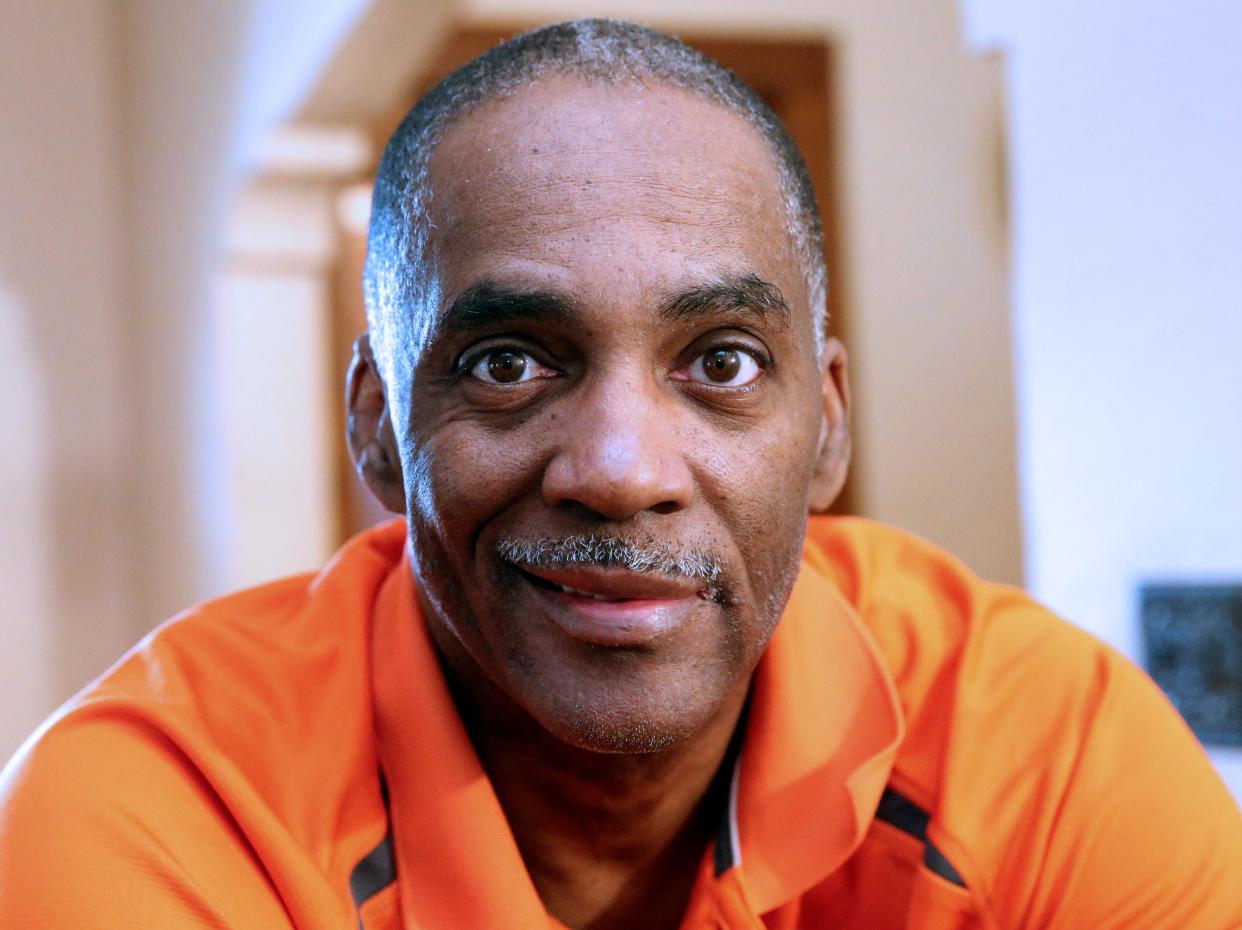

Reggie Jackson was looking forward to breakfast with his wife and mother-in-law on an unseasonably 60-degree day last November. Even before he got behind the wheel of his car, he felt exhausted. On the way to Cracker Barrel, he missed the exit ramp. Then he struck a curb while making a turn.

At breakfast, he was unusually quiet. When his wife asked him what was wrong, he told her he just didn’t feel like himself.

After dropping off his mother-in-law, the Jacksons took his wife's car for an oil change. She followed behind his car as they drove home. When Jackson was at three different traffic lights, his wife noticed how he sat there when it turned green.

When the couple arrived home, she noticed the left side of his mouth was drooping.

“She said we have to go to the hospital, now. I insisted that I was alright, but then she said, ‘Reggie, I think you had a stroke,’” Jackson recalled. He was rushed to St. Mary’s Hospital. A CT scan showed an artery on the right side of his brain was 90% blocked.

Jackson, who is African American, knows a lot of men who have had strokes and other health conditions. His brother, Daryl, died from a heart attack in 2020.

Overall, Jackson was lucky. His stroke was mild, but his case illustrates the health inequities facing Black Americans that stem from slavery that continue to ripple across the community.

African Americans are 50% more likely to have a stroke when compared to their white adult counterparts. Black men are 70% more likely to die from a stroke compared to whites, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than 795,000 people in the United States have a stroke each year, which comes to someone having a stroke every 40 seconds.

While diet, exercise, and being in good overall health can help adults individually reduce their chances of a stroke, a local physician said the overall health of Blacks as a group will not improve until America creates a restorative health equity plan for the descendants of slaves.

Jackson's stroke was a surprise, but Black health disparities are well-documented

Jackson, a local historian and co-owner of Nurturing Diversity Partners, felt relatively healthy before Nov. 9. He took daily walks along the lakefront and kept busy on the basketball court. As he got older, though, it got harder for him to keep playing basketball and find an exercise he enjoyed just as much.

He ate mostly healthy, but enjoyed his occasional steak off the grill, fried chicken, and pork chops. He also loved his food seasoned with salt.

“I didn’t realize now how much bad food I was putting into my body,” Jackson said.

In addition, he was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes three years ago, but did not regularly check his blood sugar levels.

“I should have been better checking myself, but I just didn’t like pricking my finger,” he said.

Jackson said being diabetic and having relatives who had strokes placed him in the high-risk category for a stroke.

Still, Dr. Tito Izard, President and CEO of Milwaukee Health Services, Inc., an independent not-for-profit Federally Qualified Health Center, said when assessing African Americans and their health outcomes, the medical community needs to examine things in totality and not simply look at the Black and white disparity and conclude that one or two simple changes will make everything better.

“I can easily look at someone and say, if you lose weight, workout more, and eat better then your chances of having a stroke will be reduced. While that may help the individual, I’ve learned a deeper conversation is needed when it comes to the health of African American descendants of slaves,” Izard said.

Izard, 53, a Black physician who grew up on Milwaukee’s north side, said while health disparities between Blacks and whites are wide, physiologically the groups are the same.

“We can actually directly link the poor health outcomes to the differences rooted all the way back to situations related to slavery and continued all the way through Jim Crow,” Izard said.

Jim Crow is the period after federal troops left the South as former Confederate states were admitted back into the union following the Civil War. The protections and advancements for formerly enslaved citizens were rolled back as segregation and discrimination were codified into state laws.

Izard, who uses a holistic approach that blends compassion and accountability, can relate to poor health outcomes for African Americans, even ones with high achievements.

In 1995, his son was born with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Tylan lived eight days and never made it home. His oldest daughter was only 4 pounds, 2 ounces at birth. His wife’s water broke at 15 weeks, and she was on bed rest for four months until labor was induced at 34 weeks.

Izard’s wife, who is also a Black physician, was healthy, educated, and wealthy. However, in America, according to the documentary “Unnatural Causes,” African American mothers with a college degree have worse birth outcomes than white mothers without a high school education.

“We’re talking about African-American doctors, lawyers, and business executives. And they still have a higher infant mortality rate than non-Hispanic white women who never went to high school in the first place,” according to the documentary.

Stroke struck as work in Redress Movement was just getting started

Jackson, 57, has recovered, but he still has a way to go. The stroke occurred on the right hemisphere of his brain, which caused him to have weakness in the muscles on his left side.

Fortunately, Jackson’s stroke did not require surgery, instead his blockage was treated with blood thinners and medication. He spent three days at St. Mary’s, but his rehabilitation includes physical and occupational therapy along with working with a speech language pathologist.

“I had some trouble walking for a while because of the weakness on my left side. So initially, I had to walk with someone on my side,” said Jackson,

In physical therapy, Jackson was able to increase his strength to the point of taking walks alone and walking stairs without assistance.

“I’m getting stronger and stronger each day,” he said.

The most drastic change came in Jackson’s weight falling from 174 to 154 pounds.

He credited the weight loss to a strict diet with no salt, sugar, and very low fat. He eats more fruits and vegetables. He also walks on his treadmill 30 minutes a day and spends an hour per day on his exercise bike.

“I’ve just changed the way that I look at food and basically I say anything that tastes good is usually not good for you,” he said.

Age, gender, race, family history and previous strokes all are risk factors when it comes to strokes. Those who are overweight, smokers and have limited physical activity also increases your chances, doctors say. Jackson said when it comes to health you have to manage the things you can control.

“We can all eat better and be more active. But I learned how stress also factors in as well,” Jackson said.

More:Redress Movement aims to repair damage caused by decades of racism, discrimination in Milwaukee

The stroke came about 10 months after he announced he would be a researcher for The Redress Movement, a group working collaboratively with people and organizations who want to change metro Milwaukee.

The Redress Movement is a national, not-for-profit organization, whose mission is to begin the process of redressing the damage caused by decades of legal and illegal segregation policies and practices.

Civil Rights didn’t address the problems of slavery and segregation

Historically, Izard said Black people have a higher risk for strokes and other health disparities like hypertension, obesity, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes because descendants of slavery never obtained first-class citizenship.

He said when it comes to health, one could look at the at the three-fifths clause of the U.S. Constitution of 1787 as a marker. The clause declared that for purposes of representation in Congress, enslaved blacks in the state would be counted as three-fifths of the number of white inhabitants of that state.

More:Story maps of Milwaukee, Denver, Charlotte a first step for the national Redress Movement

Three-fifths represents 60%, and Izard said descendants of slaves have yet to surpass that 60% threshold in health, education, and economic disenfranchisement in this country. Milwaukee is typically ground zero for some of the widest gaps between Blacks and whites in the nation on a range of issue.

Just look at homeownership, for example.

In the four-county metro Milwaukee area, the Black homeownership rate stands at 27.4%, compared to 70% for whites, according to U.S. Census data. That means nearly three out of four Black families do not own the home they live in, while nearly three out of four white families do.

"The slave was always considered to be a different kind of human being, and so when it came down to diagnosing the slave, there was inappropriate treatment like bloodletting or using diuretics to cure or treat the Black slave and of course these treatments did not work,” Izard said.

Not only did the treatments fail, but the slave was considered lazy or faking their illnesses.

“Everything through the Civil Rights time frame we can see that health disparities were a direct consequence of being a descendant of slavery,” he said.

When Civil Rights legislation was passed in 1964 and 65, Izard said America was able to absolve itself of the penalty of slavery without ever reconciling without reparations.

“We never redressed the issues that existed for multiple generations, so it’s not a surprise that we see the gaps we see today in health, education and economic disenfranchisement,” Izard said.

Reparations would be a good start to making descendants of slaves whole, but for restorative health equity, Izard said the following must happen:

Recognition of wrongdoing; and restitution

Empower the affected population

Stakeholder accountability; and collective collaboration

Reparative actions; and Reconciliation through Social Cohesion

A silver lining from stroke was bridging a lapsed relationship

As a griot of African American history, Jackson knows about the cruelty of slavery, and he has not ruled out those factors in the wide health care gaps. When it comes to his Redress Movement, those are some of the conversations that will be held over time.

If there was any good that came from his stroke, Jackson said he was given a second chance to be healthier and to share his story with others so they can also make changes to improve their health.

As a result of his healthy change, he said his wife, Venus Lewis-Jackson, also has lost weight as well because she is also eating cleaner.

“I would not be where I am today if it wasn’t’ for my wife,” Jackson said.

Jackson said his stroke also brought a stranger back into his life – his father, Joe, whom he did not meet until he was 19. While they tried to maintain contact, the calls became less frequent and the two barely spoke.

They tried to reconnect on other occasions as well, but after Jackson’s stroke, his father came to visit him for the weekend, and they bonded on a different level. He discovered his dad started a program for grandparents who take care of their grandchildren back in Detroit.

“I realized that’s where I got my sense of community from,” Jackson said.

In turn, Jackson was also able to show his father all his awards and plaques that he’s earned over the years. The two are now closer than they have been in years. After 57 years, Jackson said his father said something to him that he waited a lifetime for.

“He told me he was proud of me,” Jackson said, as tears streamed down his face.

James E. Causey started reporting on life in his city while still at Marshall High School through a Milwaukee Sentinel high school internship. He's been covering his hometown ever since, writing and editing news stories, projects and opinion pieces on urban youth, mental health, employment, housing and incarceration. Most recently, he wrote about a man who went to prison as a child for a horrific crime in Life Correction: The Marlin Dixon story. Released at age 32, Dixon’s intent on giving his life meaning. Other projects include "What happened to us?" which tracked the lives of his third-grade classmates, and "Cultivating a community," about the bonding that takes place around a neighborhood garden. Causey was a health fellow at the University of Southern California in 2018 and a Nieman Fellow at Harvard University in 2007.

Email him at jcausey@jrn.com and follow him on Twitter: @jecausey.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: For Black community, strokes are more than just poor health choices