How Three Italians Born In 1938 Changed Car Design Forever

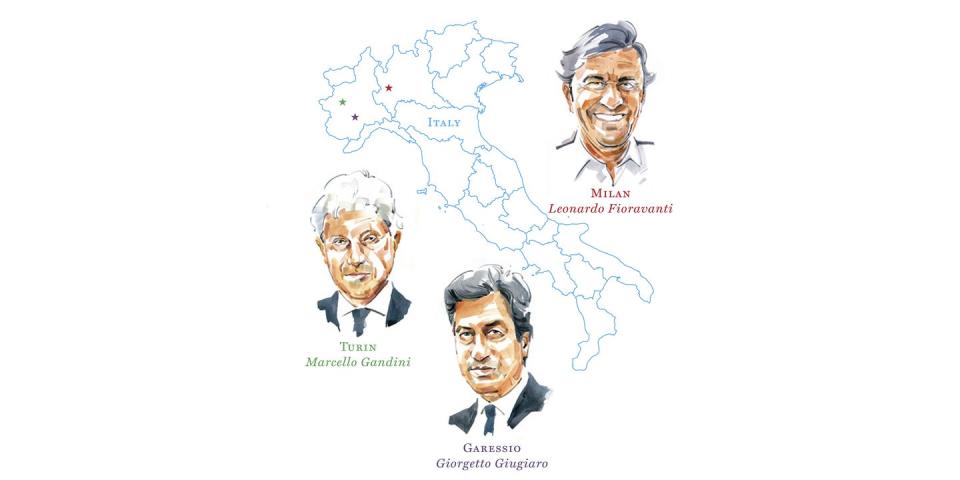

Grab a pen and a map of Italy. Put a dot on Milan. Move west about 80 miles and mark Turin. Now slide 60 miles south and a smidge east. Plop a third dot on the village of Garessio, if you can find it. Link the three to form a triangle. You’d burn more ink connecting Portland, Bangor, and Bar Harbor, Maine, but when it comes to car design, this little area in Northern Italy might as well be the center of the universe. Each point is the hometown of a founding father of the wedge-shaped, mid-engine supercar: Leonardo Fioravanti of Milan, Giorgetto Giugiaro of Garessio, and Marcello Gandini of Turin. All were born in 1938, a few months and only 100 miles apart.

This story originally appeared in the July 2019 issue of Road & Track.

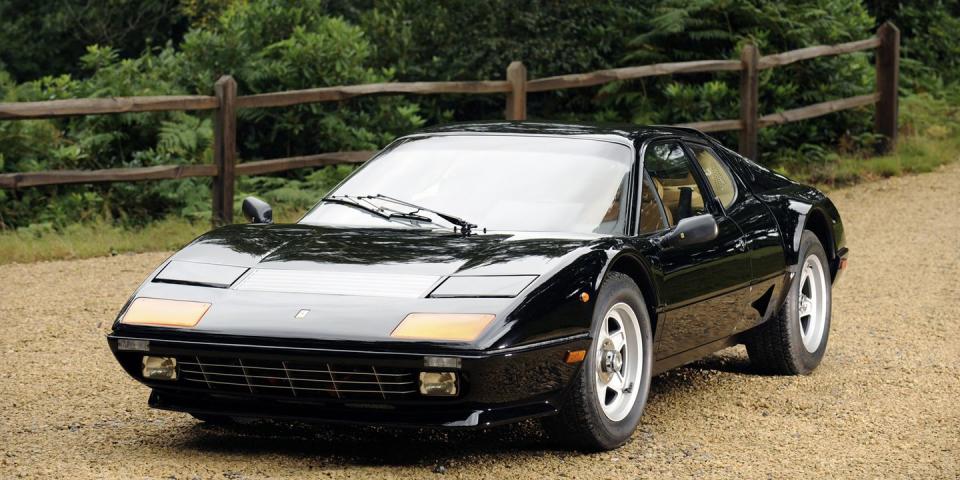

Name a sharp-nosed, mid-engine legend. Ferrari 512 BB? A Fioravanti masterpiece that defined that automaker’s golden era. Lotus Esprit? A Giugiaro design so enduring, every subsequent face-lift and overhaul across 28 years of production maintained the same shape and style. Lamborghini Countach? Gandini’s gift to the world of motoring and the bedroom-poster industry. If your favorite car has two seats, a midship engine, and a profile like a doorstop, it likely owes its existence to one of these three men. It’s enough to make you wonder what was in the water. How did this tiny triangle of Italian soil give rise to three titans of modern design? To find out, we asked the designers who’ve shaped some of our favorite modern sports cars, people like Chris Bangle, Ed Welburn, Ralph Gilles, Moray Callum, and more.

Fioravanti is responsible for an entire generation of iconic Ferraris. He trained as a mechanical engineer, focused on aerodynamics, and joined Pininfarina in 1964, straight out of school. He immediately started designing amazing machines. Name a memorable Dino or Ferrari of the past 50 years and you’re likely to land on a Fioravanti design. A partial list: the 1967 Dino 206 GT, the 1968 365 GTB4 Daytona, the 1975 308 GTB, the 288 GTO, the Testarossa, and the F40. All Fioravanti works. “I’m still surprised that Fioravanti was an engineer,” says Welburn, former head of global design at General Motors. “In general, engineers just don’t do creative, beautiful automobiles. And he did.”

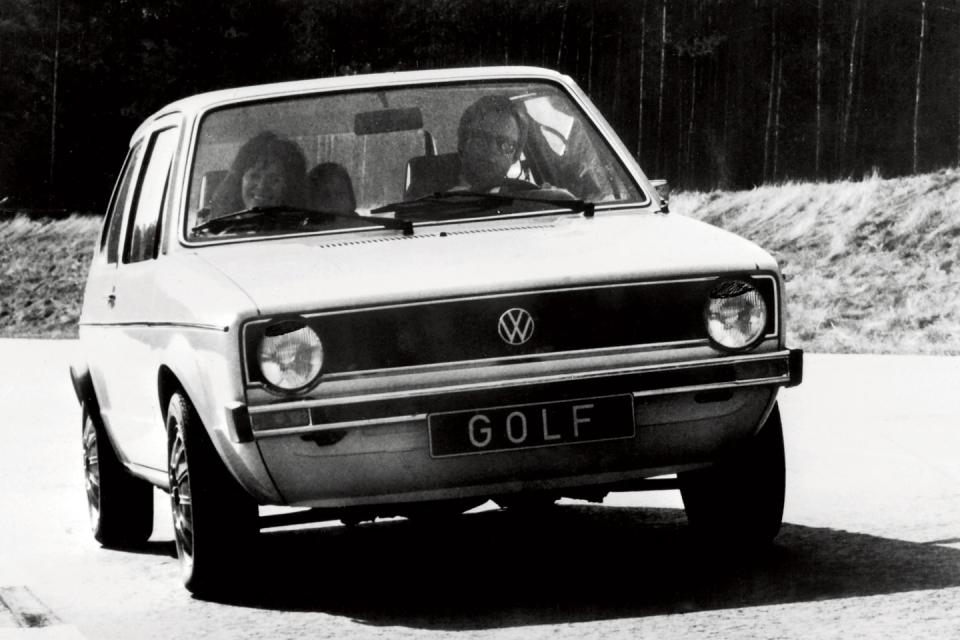

Giugiaro apprenticed at Fiat, passed through Bertone and Ghia, and in 1968, founded his own design firm, Italdesign. He penned outrageous concept cars, such as the Bizzarrini Manta and Porsche Tapiro, exotics like the De Tomaso Mangusta and the Maserati Bora, and icons like the Esprit, the BMW M1, and the DeLorean DMC-12. He styled normal cars, too—he has called the Mk1 Volkswagen Golf of 1974 his best and most important design—in addition to Nikon cameras, Seiko watches, and Beretta firearms. “He showed the world that a mass-market product can have attractive and iconic design,” says Ralph Gilles, head of design at Fiat Chrysler Automobiles.

Gandini joined Bertone in 1965, after Giugiaro left. The next year, he rocked the world with the debut of the Lamborghini Miura. It was the first road car with a mid-mounted V-12 engine, the original supercar. Four years later, Gandini showed the most radical concept car in history: the Lancia Stratos Zero, a sci-fi wedge. It inspired the production Lancia Stratos, a slightly more practical automobile that dominated rally racing. And of course, there’s the Countach. Hard to believe, but the totem of 1980s angular excess debuted in 1971, just five years after the voluptuous Miura. “For me,” says Mitja Borkert, current head of Lamborghini design, “everything that we do relates to the design DNA that the Countach gave us.” It wasn’t just Lamborghinis: Gandini penned the first BMW 5-series and the Renault 5 Supercinq, too.

Style is part of the bedrock of Italian culture. There’s a philosophy, fare bella figura. Directly translated, it means “to make a good figure”; in practice, it’s more like, “make an effort to be noticed” or “nail the first impression.” This is the nation that took something as universal as an evening stroll and elevated it to la passeggiata, a daily ritual of well-dressed, leisurely flaunting and flirting. “Just holding a pencil in this country makes you feel more creative,” says Bangle, BMW’s former design chief.

The culture is also permeated by a reverence for aesthetics. “I think [Italians] have respected art and design probably longer than any other country,” says Callum, vice president of design at Ford. Early in his career, Callum worked at the Ford-owned design house Carrozzeria Ghia in Turin. He felt a major cultural difference almost immediately: In Italy, his chosen career held a place of honor that he’d never experienced growing up in Scotland. “Being an industrial designer in the U.K. is not seen as a really high, important job,” he says. “Whereas I think in Italy, they see the art side of life as being very, very important. I think that element of where you are in society really helps.”

It goes back generations. Italy’s carrozzerie, independent styling houses that designed and built bespoke automotive bodywork, grew from a tradition of horse-and-buggy coachbuilding. Trace the craft even further, and you end up in the Middle Ages, when Turin had a reputation for turning out the world’s most beautiful and stylish suits of armor.

“Metalworking has always been a primary craft there,” says Peter Stevens, designer of the McLaren F1 (and dozens of other cars). In his current role, teaching at London’s Royal College of Art, he emphasizes how Italy’s past helped to elevate the work of coachbuilding and, eventually, car design. “Unlike in other countries where metalworkers were seen as… the grumpy guys at the end of the village that you wouldn’t want your daughter to marry, in Italy that was seen as a really stylish thing that a family would be very proud of,” he says.

The culture helped steer Fioravanti, Giugiaro, and Gandini toward car design. So did the timing of their births. Arriving in 1938 meant their earliest years were defined by the unimaginable destruction of World War II. Having survived, these young men entered automotive design in an era of unbridled innovation and postwar optimism.

Welburn marvels at what it must have been like growing up in that time and place. “You can imagine them as teenage boys, being excited about what’s going on. By age 20, which would be 1958, all three of these guys had reached [adulthood] at the exact same moment that Italian automobile design was on fire. And I don’t care what your interests were, you wanted to be a part of it.”

One more factor that influenced how Fioravanti, Giugiaro, and Gandini designed cars: plaster. Most automotive design departments build full-size models out of clay. The technique was pioneered by Harley Earl, the visionary who shaped General Motors design from the ’20s through the early ’60s. Earl grew up in Hollywood, and he swiped the modeling-clay trick from the movie industry. It’s a great way to quickly get a design off the page and into three dimensions, tweaking and editing the shape in real time via the addition or subtraction of material.

The carrozzerie didn’t use clay. They adapted the sculptor’s tradition of making a plaster maquette before taking chisel to stone. Fioravanti, Giugiaro, and Gandini all worked with master modelers, practicing a form of plasterwork that had been handed down through generations, and that tradition informed their designs.

These plaster modelers were “startlingly skillful fellows,” Stevens says, who could understand the shape you were looking for “by the way you waved your arms.” The plaster had limitations: It didn’t allow for really dramatic curves, and unlike clay, it offered less opportunity for rework. “In a way, the plaster method caused them to have a lot more discipline,” Stevens says, “because if you screwed up, you’d have to chop the whole lot off and start again.”

“The way they developed the shapes, I mean, it could have been 500 years ago, 800 years ago, 1000 years ago,” Welburn says. “It’s like they’re working on marble.” He mentions some quintessential wedge-shaped concept cars. “When I look at those long, lean surfaces, I can see the sculptors working in plaster on those cars. I can really see how plaster had an effect on what they were doing.”

Stevens says it wasn’t until the late ’80s that the American tradition of clay modeling made its way to Italy. “Now they all use exactly the same tools. They no longer seem to have that difference in Italy, which I always liked.”

Fioravanti, Giugiaro, and Gandini are all still alive and active in the design world. They aren’t easy to get ahold of. Some of this is due to language barriers, and some is likely by design. I tried to reach Giugiaro and Gandini with no success, but I did get to talk to Leonardo Fioravanti. He graciously dedicated the better part of a Saturday evening to our chat.

The conversation was freewheeling and joyous, as wide-ranging as the man’s half-century-plus career. Fioravanti is a modest man, but his accomplishments cannot be diminished. The best instrument of personal freedom, he told me, is the car. That’s why his countrymen love them and why certain Italians have the ability to design them correctly. Fioravanti is the oldest of the trio—born in January of 1938, followed by Giugiaro and Gandini in August. Marcello and Giorgetto both love cars, Fioravanti said. And when you love cars, you stay young.

I asked him about the philosophy behind his designs. Start from function, he says. Function is the same thing anywhere in the world—a wheel must be round, a door must open. Then comes aesthetics, the way something appears to the eyes. Finally, the way that a person feels about the aesthetics? That’s style.

Perhaps in the beginning, he says, beauty is not so fascinating. Sometimes we get distracted by more flashy things. But after five, 10, 20 years, true beauty can only become more and more attractive. Italians have a natural approach to function, he says, to style and aesthetics and originality. They have the uncommon courage to pursue simplicity.

Fioravanti mentioned the Ferrari Daytona (pictured above), an undeniably gorgeous design. He didn’t set out to make it beautiful when he created it. The first function of a Ferrari, he says, is to win. The car needed good visibility, good aerodynamics, an extraordinary engine. It won its class at Le Mans in 1972, 1973, and 1974. One year, Daytonas swept the first five places in their class at that legendary race. To Fioravanti, the car’s beauty is a result of how well it functioned in the crucible of motorsports.

To drive home his point, Fioravanti quoted Plato: Beauty is the splendor of truth. And if you begin with the truth, he says, there’s a good chance you’ll arrive at beauty.

It’s a philosophy embodied in every enduring design. It’s a guiding principle more powerful than culture, region, or era. It’s what allowed Fioravanti, Giugiaro, and Gandini to become the most important men in car design. In everything they did, they found truth. And from a tiny wedge of Italy, they gave it to the world.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos