Three witnesses speak during Vineyard land case trial; no verdict yet from judge

MARTHA'S VINEYARD — The Devine family and Vineyard Conservation Society faced off in court Thursday over ownership of a 5.7-acre parcel of land in Gay Head (Aquinnah).

Nineteen defendants, including members of the Devine family, are fighting for the land, also known as Lot 240, which was donated by the Kennedy family to Vineyard Conservation Society in 2013.

The Devine family says it owns the land through their ancestor Louisa Pocknett, but Vineyard Conservation claims it owns the land based on a chain of title extending from Henry Cronig, a one-time real estate mogul, who died in 1972.

Pocknett is described in the original complaint as the former owner of the property. She died on Aug. 29, 1874, and was a member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe.

In court Thursday, Judge Karen Goodwin didn't immediately render a verdict, said Jonathan Polloni, a land use attorney for Senie & Associates, PC, who represents the Devine family. The trial, he said, included complex arguments that extend back to events that occurred in 1870, 1878, and 1887.

From the archives: Cape Cod family continues to fight for 5.7 acres of land on Martha's Vineyard

"A lot of time has passed and there's a lot of ground to cover," he said. "I think overall it went well and the judge did a great job working to understand the issues and the facts. It's a hard case to decide."

The bulk of the day surrounded statements given by Candace Nichols, a title examiner and witness for Vineyard Conservation, Polloni said. Nichols was the main witness for the organization.

Despite the absence of a title examiner for the defendants, Polloni said there isn't much else his clients are disputing.

"It's more about the records that do exist, and how they are interpreted," he said.

Brendan O'Neill, executive director of Vineyard Conservation, also testified and explained the environmental qualities of the land.

"Brendan gave a speech about what makes this land unique and special to his organization — which everybody can appreciate and understand," Polloni said. "But, this case isn't about wetlands or endangered species for my clients."

O'Neill, executive director of Vineyard Conservation, declined to comment other than to say he is awaiting the court's determination in the case.

Rebecca Devine, a defendant in the case, and a member of the Gay Head (Aquinnah) Wampanoag tribe, took the witness stand unexpectedly, Polloni said, and spoke directly after O'Neill.

Devine said she's sensitive to O'Neill's concerns regarding the biodiversity surrounding Lot 240, and the rest of Moshup's Trail, but contends O'Neill's testimony dehumanizes Wampanoag people.

"It should not be forgotten that Wampanoags too are endangered," Devine said in an email to the Times "We feel that our mission to preserve the native lands of our ancestors should be our right and not theirs simply because they are a conservation organization. We refuse to be overshadowed by microorganisms and rare species."

More: 5.7 acres in Aquinnah, a Kennedy donation, a Wampanoag ancestor all part of court case

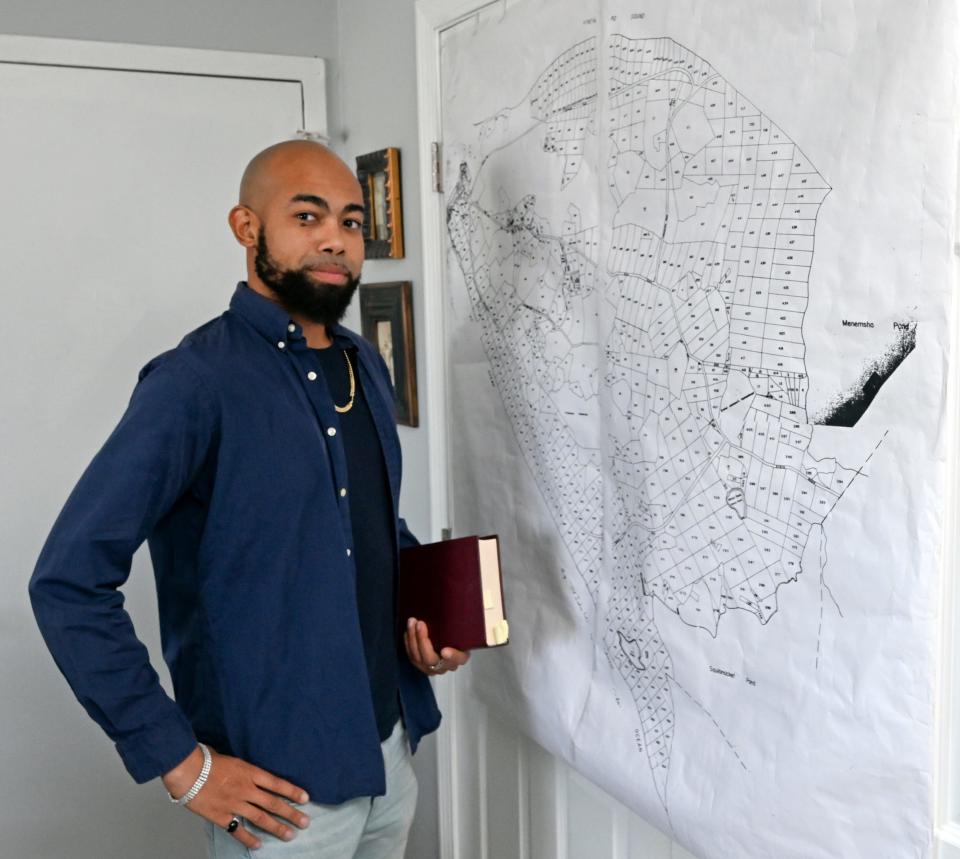

Troy Small, another Gay Head (Aquinnah) Wampanoag tribal member, said his family supports Vineyard Conservation's mission of environmental protection, but he believes it's his family's right to preserve that land. Small grew up on Martha's Vineyard.

"It's just as much our right to preserve the land, its species and our culture on the land of our ancestors," he said in an email. "For too long, Indigenous people and the individuals in our tribe have been overlooked and marginalized."

What didn't make it to court

Something that didn't make it into trial, said Polloni, is the historical disposition of land, throughout Martha's Vineyard, and Cape Cod, including Mashpee.

Throughout different points in time, he said, land was given back to tribal members on an individual basis by settlers, and then taxed — a concept that was not traditionally a way of life for Wampanoag people.

It's ironic, he said, that tribal members are, again, seeking to have land returned to them, that was already once returned in the past.

"What you see in the chain of title here, is that all the Devine lots were taken for taxes and that happened right before the sale to Henry Cronig of all these lots," he said. "They (the Devines) are being dispossessed of the lands they have as tribal members. They are seeking to have the land returned to them and it’s getting taken away a second time."

Original complaint initiated by Vineyard Conservation

Originally, a complaint was filed by Vineyard Conservation in May 2017, to decipher who Lot 240 was deeded to in 1870, said Tanisha Gomes, a defendant in the case.

Gomes said the land was deeded to her and the other defendants by her ancestor Pocknett and was never legally sold. The land in question, she said, is currently listed on the town of Aquinnah's Board of Assessor's website under her family's name.

Vineyard Conservation bases its claim of ownership to Lot 240 on 1944 and 1945 deeds, which they say, assert that Horace Devine, Louisa Pocknett's grandson, gave Cronig the entirety of his family's land, including Lot 240.

Since 1945, the land in question passed through several layers of ownership, eventually landing in the hands of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis in 1978.

Gomes said Lot 240, or "240," which it's also commonly called, is a parcel that was included in a 2013 gift deed between Caroline Kennedy, Jacqueline's daughter, and Vineyard Conservation.

According to gift deed documents provided by Gomes, the Kennedy family, through its Red Gate Farm LLC, donated 30 acres of its Aquinnah property to Vineyard Conservation. The land, which was valued at $3.7 million, was gifted for $10.

While the 1944 and 1945 deeds specify lots that were sold to Cronig by Horace Devine, with a certain dollar value attached, said Gomes, Lot 240 is not named or described in either deed.

Verdict could take weeks to decide

Because of the many complicated aspects of the case, Pollini said the judge could take up to a month before making a ruling.

"It depends on the judge's caseload and what other cases she has to hear and how complicated they are," he said. "But I think she’s trying to resolve this in a shorter amount of time."

This article originally appeared on Cape Cod Times: No verdict given during Aquinnah land case trial