'It's like a time capsule': Lake Michigan shipwreck found intact off Algoma after sinking in 1881

ALGOMA - It could have been just another long-lost cargo shipwreck finally discovered this summer at the bottom of Lake Michigan.

But the 142-year-old wreck of the Trinidad, in about 270 feet of water far off the Algoma shore, instead is considered by its finders as one of Wisconsin's most important wrecks.

That's because the remains of the 140-foot-long schooner are intact, not broken up like other wrecks in the Great Lakes. Its deck house still has dishes, the crew's possessions and other artifacts inside. Her anchors, wheel, bell and other deck gear remain present.

Even the rigging, which in the Trinidad's case used wire instead of the usual rope that would have rotted away, survives, giving marine archaeologists a very rare chance to directly study how the 19th-century cargo ship was rigged.

And modern technology allows those interested to visit the wreck virtually.

"It's one of the most intact shipwrecks ever found in Wisconsin waters," said Brendon Baillod, president of the Wisconsin Underwater Archeological Association. "It's a very significant find. It's not a famous ship, but there are very few ships like it in Wisconsin waters. … It's like a time capsule."

Finding Trinidad

Baillod and fellow Wisconsin Underwater Archeological Association member Robert Jaeck found the remains July 15, capping a two-year search by the maritime historians.

Baillod first became interested in the Trinidad about 20 years ago when he started putting together a database of all known vessels lost in Wisconsin waters. In an article he posted on the Shipwreck World website, he wrote that he felt the lost schooner was a strong candidate to be found because the crew, all of who survived, gave a good description of where she sank.

Using historical documents, Baillod narrowed down the Trinidad's location to a roughly 25-square-mile grid about 10 miles from shore, and he and Jaeck began using sonar to search for her.

"This one ticked all the boxes for discovery," he said. "It was not very well-known, not far from a port, few people if any looked for her, and we had a 5-by-5-mile base where we figured it would be."

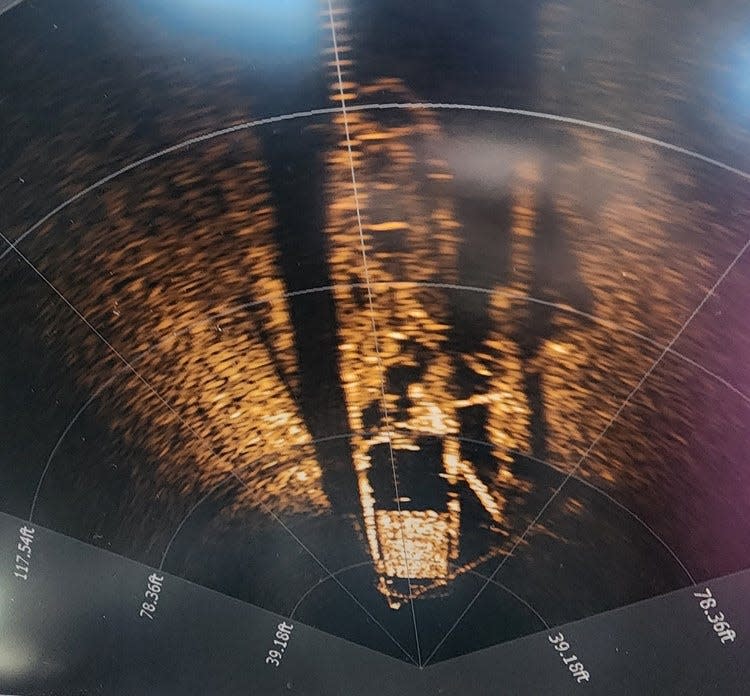

Baillod and Jaeck used a low-frequency sonar well below the surface of the water to create a three-dimensional map of the bottom of the lake, nearly ⅓-mile wide on each pass. When they first saw an image of the wreck, they almost missed it because it appeared as little more than a smudge.

But they turned back for another pass at the same spot at slower speed and were clearly able to see the shipwreck, almost exactly where she was reported to have sunk.

"When we found it, we were stunned," Baillod said.

The ship and the sinking

According to Baillod's research, the Trinidad was built in 1867 in Grand Island, New York, by shipwright William Keefe. Her main purpose was to ship grain; she would carry coal from Oswego, New York, through the Great Lakes to ports in Milwaukee and Chicago, then return to New York hauling grain from Wisconsin, an extremely valuable and lucrative commodity at the time.

But Baillod noted while the Trinidad made much money for its owners, they apparently didn't spend much to maintain the ship, which was suffering from decay and hull leaks within 10 years. By 1879, it was no longer fit to haul grain. While carrying coal in May 1880, she struck a reef in Lake Superior that tore out 10 feet from her bottom, which was "hastily repaired."

In May 1881, the Trinidad was bringing coal from Port Huron, Michigan, to Milwaukee. After passing through the Sturgeon Bay canal May 10, the vessel began leaking more than usual, and even the extra pumps fitted to her could not prevent the water from continuing to rise in the hull.

At 4:45 a.m. May 11, the Trinidad suddenly lurched and began sinking rapidly. The crew had no time to gather their possessions or weather gear before boarding their small yawl boat, and the ship sank so quickly that a Newfoundland that served as her mascot was unable to escape.

Capt. John Higgins and the eight-man crew, all feeling the effects of the cold and the wet, rowed eight hours in the yawl through the waves of Lake Michigan before landing in Ahnapee (present-day Algoma) at about 2 p.m. They later were taken by schooner to Chicago where Higgins reported the loss.

Higgins told reporters he believed the Trinidad sank because of hull damage from ice while the vessel was in the Straits of Mackinac several days prior, but Baillod wrote that her lack of maintenance likely played the main role.

"A review of the vessel’s career suggests that she was little more than a floating coffin by the time of her final voyage," he wrote on the Shipwreck World site. "The insurance records suggest that Trinidad received little of the normal maintenance and was essentially sailed into the bottom of the lake."

Sonar helps with confirmation

Baillod and Jaeck didn't immediately publicize their discovery but instead reported it to the Wisconsin Historical Society’s Maritime Archaeology program so it could be documented before any possible disturbance of the wreck occurred.

All shipwrecks in U.S. waters are protected by the federal Abandoned Shipwreck Act of 1987, which essentially makes the wrecks archaeological sites, as well as related state laws, Baillod said. However, he noted the danger of not just pillaging by artifact hunters but also damage to the wreck from dive boats hooking their anchors into the remains, which though intact are quite fragile.

Plus, while they were sure of what they'd found, they couldn't make a definite ID from the water's surface.

"You feel great responsibility," Baillod said. "We knew we had to do a lot of work, write (the ship's history) up, tell its story, because we were the only two people in the world who knew where the site was, who have the coordinates."

After they contacted the historical society, state maritime archaeologist Tamara Thomsen made arrangements with Crossmon Consulting, a Minnesota-based firm specializing in drowning victim recovery and underwater exploration, to survey the site with a remote-operated vehicle with sonar, which measured the vessel’s hull with extreme accuracy.

Those dimensions then were compared to the dimensions given on the Trinidad’s original customs house enrollment documents, and they matched, confirming the wreck's identity.

Strolling the deck (virtually)

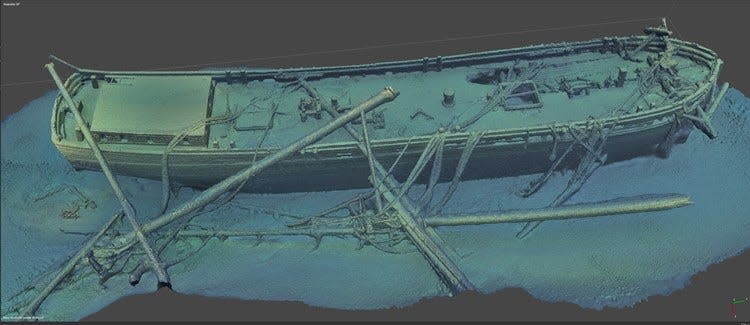

After the wreck was confirmed as the Trinidad, Thomsen returned to the site with diver Zach Whitrock to photographically document the wreck and its artifacts. During a three hour and 20 minute dive, Whitrock shot 3,600 high-resolution images while swimming around the ship and into its interior, as well as walking on the deck.

Those images were used to construct a 3-D photogrammetry model of the wreck that rotates fully in all directions. Those interested can take a flyover look at the model on YouTube, and visitors to the Sketchfab website can use a virtual reality headset to virtually walk on the Trinidad’s deck as she now sits, 270 feet below the surface of the lake.

What's next?

Baillod and Jaeck plan to work soon with the Wisconsin Historical Society to nominate the site of the Trinidad to the National Register of Historic Places. Baillod said the wreck lies just outside the borders of the Wisconsin Shipwreck Coast National Marine Sanctuary, so recognition as a historic place would bring greater visibility to it as an important part of the history of Algoma and the surrounding area.

Once the site is on the National Register and thoroughly documented, its location will be made public so technical divers can visit her without harming the fragile hull or its historical artifacts.

"We're pretty stoked," Baillod said. "This is an important one."

Our subscribers make this coverage possible. Click here to subscribe to a USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin site today and support local journalism.

This article originally appeared on Green Bay Press-Gazette: Intact Lake Michigan shipwreck that sank in 1881 found off Algoma coastline