Is it time to consider a new land ethic for Washington County?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

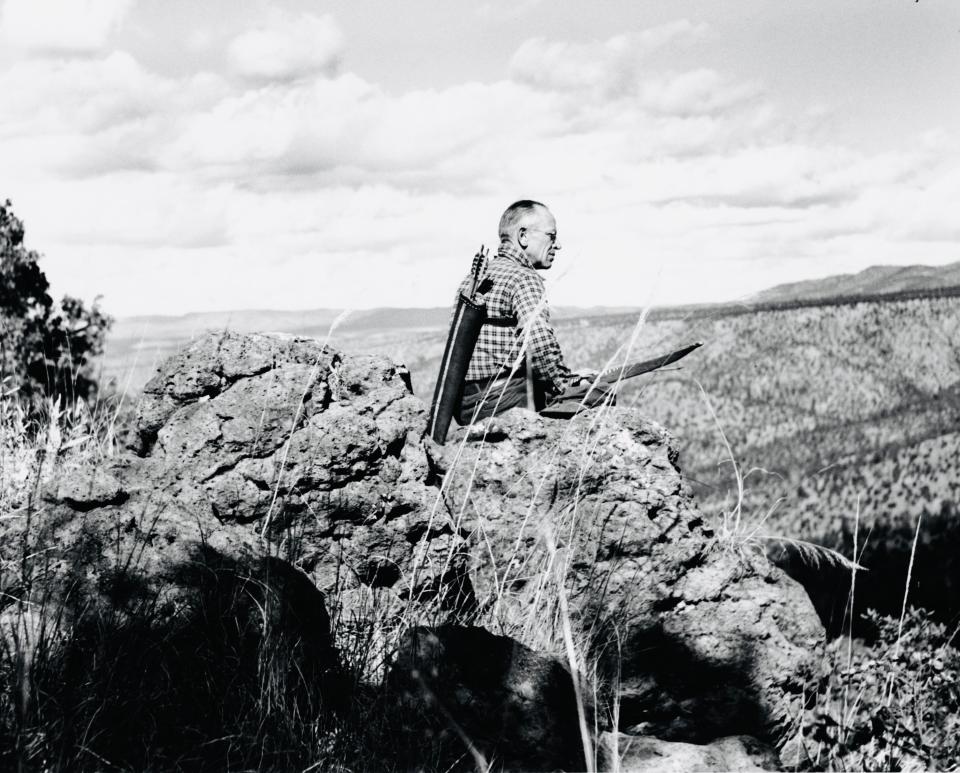

— Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac (1949)

During the holidays, one common conversation with neighbors involved changes in the local landscape in 2023.

This last year has seen a continuing replacement of fields and forests with huge warehouses, the building of new strip malls in spite of myriad vacancies in existing strip malls, a growing buffet of fast food outlets and the construction of new gas stations right next to existing gas stations (we will have three in one block in my neighborhood shortly).

These changes are not inevitable nor healthy.

Seventy-five years ago, Aldo Leopold’s "A Sand County Almanac" offered a new direction for human interactions with the land. Although a lot has changed since 1949, Leopold’s words and ethics still provide a timely environmental guide.

Leopold wrote in the wake of a localized climate change. The 1930s Dust Bowl arose during one of the hottest and most arid periods in North American history, which should sound familiar to many of us today.

In looking back at the destruction of our nation’s lands, Leopold proposed a new “land ethic” where humans expanded ethical rights beyond their own species to include all our planetary animal and plant neighbors and the habitats we all call home.

The other classic environmental fable for our region is Garrett Hardin’s classic 1968 article, “The Tragedy of the Commons.”

Hardin observed that in common areas it can be advantageous for some to degrade or pollute that habitat if they reap all the profits and bear none of the costs. Although many developers are strong advocates of private property rights (as am I as a homeowner), they are silent on the myriad social costs.

A lack of green space, increasingly congested roads, declining quality of life and the opportunity costs of focusing an economy on lower-paying jobs are just some of the costs of degrading our commons. While the profits from new warehouses, gas stations and fast food outlets go entirely to the developer, the costs are shared by the public.

Less green space has been shown numerous times to cause health issues. Traffic congestion causes accidents and stress. Impermeable surfaces pollute our waterways and destroy recreational opportunities.

These “indirect costs” are offloaded on all of us citizens of our natural community, with no clear benefits.

Lest this discussion of environmental thinkers seem too esoteric, let me end with a simple wish for all the regional citizens as they consider how to treat our shared land resources when planting trees or parking lots. Leopold suggested we follow this simple dictate: “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”

If all of us follow this New Year’s resolution, 2024 will provide a gift we give ourselves — a healthier habitat.

Mark Madison lives in Hagerstown and teaches environmental history, ethics and policy at Shepherd University in Shepherdstown, W.Va.

Will a bird by any other name still tweet?

Colleges and the environment are both in peril. But protecting one could save the other

This article originally appeared on The Herald-Mail: It might be time to examine the way humans are using our land